For several weeks, a social media campaign has been making serious allegations against Southwark Council over 120 residential properties it has begun to build in Peckham. A Twitter feed has repeatedly claimed that, to use its own words, “Our elected local authority is destroying a public park to create luxury private housing without having consulted local residents”. Shocking if true. The reality, of course, is rather different.

For a start, the piece of land in question is not a “public park”. Yes, it is covered in grass and, yes, members of the public have, until very recently, been free to spend time there. But it is not a “public park” in the sense of being created for that purpose or protected against being built on by planning law designations, as is the case with hundreds of public parks in the capital, both large and small.

In truth, it is and has been for many years, earmarked for development. The social media campaign refers to it as “Peckham Green”, saying that is a local name for it, but the council calls it the Flaxyard site, after a company that used to own it and is said to have once intended to build offices there. By the early years of this century it had passed into the council’s hands and was earmarked by it for potential use as part of the Cross River Tram project, a scheme supported by Mayor Ken Livingstone which would have linked Camden Town and Brixton by way of Waterloo Bridge.

Boris Johnson canned the tram idea after succeeding Livingstone as Mayor in 2008, but Southwark hoped it might be revived and kept the site empty accordingly, allowing it to remain grassed over. In 2014, the council, amid London’s soaring population and deepening housing shortages, adopted an area action plan for Peckham and next door Nunhead, with a view to building around 2,000 new homes in those neighbourhoods and more office and retail space.

In the action plan, the Flaxyard site was formally “safeguarded” for potential Cross River Tram use – such measures are routinely taken in anticipation of large infrastructure schemes – but even by then there was little sign of the tram project ever happening, and the council had already looked into putting the land to different use.

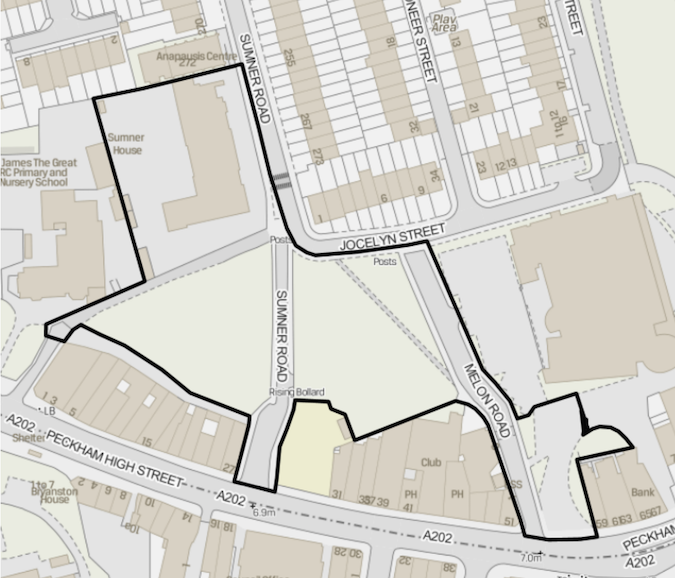

In 2016, it came up with plans to build housing there as part of a scheme that also took in Sumner House, a former school building on a site adjacent to Flaxyard where the council’s children’s services department is based (see map from council document below). Towards the end of that year, contrary to the claims of the social media campaign, the local public was consulted about the plans, as the law requires.

When Southwark’s application came before Southwark’s planning committee on 28 March 2017, the officer report listed around 500 addresses that had been embraced by the consultation and recorded that six comments raising various objections had been received. Among these was the loss of the Flaxyard as open land. The report’s response was, entirely correctly, that the site was allocated for redevelopment in the Peckham and Nunhead area action plan and had “remained vacant for a significant period in anticipation of a development scheme” (page 112).

Elsewhere, the report says: “The council’s commitment to the redevelopment of Flaxyard is…a long standing ambition and in this context little weight can be placed on maintaining the vacant space as a public green space in perpetuity.” (page 81). In other words, whether or not the site in question is referred to as “Peckham Green” it has never been and was never going to be a “public park” except in a rather loose use of the term on a temporary basis.

And what of the social media campaign’s third claim, that the Flaxyard or Peckham Green land is to be “destroyed” so that “luxury flats” can be built? It is entirely false. In the original application, the proposal was for Sumner House – which, as shown above, is next to and separate from the grassed over Flaxyard site, not part of it – to be converted into housing for private sale. The idea was that the proceeds from those properties would help to pay for the homes to be built on the Flaxyard site, all of which were to be “affordable”. In all, a pretty routine example of the commonplace cross-subsidy model of affordable housing finance.

There have been changes since 2017, including the council undertaking the development itself, rather than the Clarion Housing Association as was originally intended. But the tenures of the homes to be built on the Flaxyard site, on either side of the pedestrianised part of Sumner Road that bisects it, continue to be wholly of “affordable” types and not for private sale, “luxury” or otherwise. Southwark’s website tells us there will be 120 dwellings in the development, of which 96 will be for social rent and 24 will be other “genuinely affordable” types, almost certainly shared ownership. Work on clearing the site is already underway.

Meanwhile, the conversion of Sumner House into homes for private sale has been put on hold. The main reason is that at the time of the original planning consent Southwark was intending to build some new council office space, into which its children’s services department would be moved, vacating Sumner House. But that idea has been set aside, largely because the possibility of more council staff working from home on a long-term basis in the aftermath of Covid means it is hard to know how much office space the council will now need.

Councillor Stephanie Cryan, who is Southwark’s Cabinet Member for Council Homes and Homelessness, says she doubts any redevelopment of Sumner House will happen soon. The costs of building the affordable homes on Flaxyard will be found from other sources, such as Right to Buy receipts and grants.

Does all this mean that the dismay of local people who’ve come to value the Flaxyard site as a green space and have been taken by surprise by the appearance of builders’ hoardings should be dismissed as unimportant? Of course not.

At the same time, it should be recognised that Southwark – as Cryan has emphasised on Twitter and when appearing on Vanessa Feltz’s BBC Radio London show (from about 65 minutes) – has 15,000 households on its waiting list, half of them including children, and a staggering 3,200 families in temporary accommodation in the borough, much of it wholly unsuitable for them. If homes to house at least some of those families in desperate need are not to built on a council-owned site long earmarked for development, where should they be built instead?

Still, the consultation was a long time ago – almost five years. Cryan, who took up her current cabinet role in February, accepts that it would be reasonable to argue that Southwark could have done more in more recent times to at least re-alert local people to what was going to happen, though of, course, Covid has limited the sorts of consultation exercise that can be carried out. She says she is putting her mind to how consultation processes in general might be improved in future. She has also pointed out that Sumner Road Park and the Surrey Canal Walk are a block or two away.

Meanwhile, the social media campaign against the new council housing continues, featuring vox pop clips of people described as local responding with disquiet to the campaign’s allegations about the council. A driving force behind the campaign is Nunhead resident Lewis Schaffer, a local radio host and stand up comedian. There has been no response from the Save Peckham Green campaign to an email asking it to justify its more questionable claims or by Schaffer to an invitation to get in touch.

On London is a small but influential website which strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.