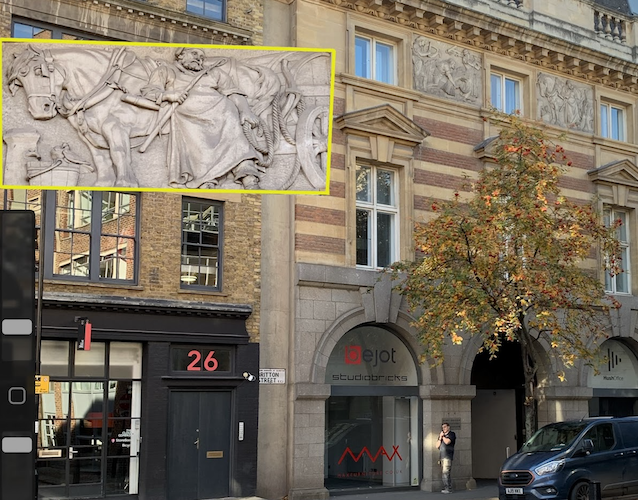

Pause for a while in front of the easily missed friezes in Britton Street, pictured above. They are all that remains of the once mighty Booths distillery, which was at the centre of Clerkenwell’s astonishing relationship with gin. Two other Clerkenwell gin giants, Gordons and Tanqueray, have also long since left the area.

So has J. & W. Nicholson, one of the earliest and biggest distilleries, which purchased a site on Woodbridge Street in 1808 before moving to a larger one on St John Street in 1828. Nicholson’s classic London dry gin, made using botanicals such as juniper, angelica and liquorice, and said to be the Duke of Wellington’s favourite tipple, was exported around the world.

It was the area’s celebrated waters – which gave rise to the names Clerken-well and Gos-well Road – that made it a magnet for these well-known gin distillers, though the area also had a bit of previous with “mother’s ruin”.

Turnmill Street and surrounding roads were one of the epicentres of the gin craze, which all but brought London to its knees during the 1700s. Its debilitating effects were everywhere, as most famously captured by William Hogarth in his painting Gin Lane. It is reckoned that over 6,000 houses in the capital were selling and making gin, often in sordid conditions.

It is easy to understand why the gin craze took hold at a time when poverty was rife and drinking water was contaminated. Gin offered an instant distraction from the mind-blowing misery of everyday life, but its effects were mind-numbing in more than one sense. Henry Fielding, author of Tom Jones and a Bow Street magistrate, warned that if nothing was done to tackle the problem of excessive gin drinking, there would soon be “few of the common people left to drink it”.

Magistrates in Middlesex lamented that gin was “the principal cause of all the vice and debauchery committed among the inferior sort of people”. Some estimates suggested that an amazing 50 per cent of the country’s annual wheat production was given over to gin production – a nice little earner for farmers, which they were reluctant to lose.

From 1729, the government introduced a succession of laws to curb gin drinking, but it was not until the 1751 Gin Act, which put small unlicensed gin shops out of business, that consumption dropped dramatically and the nation woke up from the biggest hangover it had ever experienced. The Act paved the way for bigger “respectable” corporations to move into the market, which they did. Lured by the magic of its clean waters, they made Clerkenwell the gin centre of the world.

The Booth family, which claimed to have been in the wine business since 1569, relocated to London from the north-east of England. In 1740, they established their first distillery at 55 Cowcross Street, within a neighbourhood where many of the backstreet gin shops had flourished and expanded into Britton Street in 1770. With the help of another distillery, based in Brentford, Booths became for a while the biggest distiller in England.

Alexander Gordon, a Scot, built a distillery in Southwark in 1769 before moving to Clerkenwell in 1786. In 1898, his company merged with Charles Tanqueray & Co, which had originated in Bloomsbury just below the British Museum at 3 Vine Street (today’s Grape Street. Photo below).

All production by the new Tanqueray Gordon company was eventually moved to Gordon’s Goswell Road site in 1899, setting the stage for it to consolidate its position as the biggest gin company in the world, thanks largely to huge sales in the US. The building that housed Gordon’s distillery can still be seen at Goswell Road’s corner with Moreland Street. Charles Gordon, the last of the Gordon family to be associated with the business, died in 1899,

The whiff of gin has long evaporated from Clerkenwell, just as its watch and clock businesses have largely gone. Today, it has been colonised by media industries, work units and architects, together with restaurants and supportive companies. Tomorrow? Who knows. The economic outlook is as misty as ever, but the resilience of Clerkenwell is not in doubt. It knows how to re-invent itself.

This article is the ninth of 25 being written by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in Holborn, Farringdon, Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury and St Giles, kindly supported by the Central District Alliance business improvement district, which serves those areas. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.

Brand new distillery in Bride Lane, EC4, just off Ludgate Circus. https://www.cityoflondondistillery.com/

Agreed – should have said “was buried”

[…] Murray & Co. (below) employed 300 people in Turnmill Street and the headquarters of Booth’s Gin was based in and around it for 200 hundred […]