Steve Norris has a long and distinguished record in championing better transport in London. But he’s off track in his criticism of Crossrail 2, the planned north-south cross-London rail route (“We need to think again about Crossrail 2“, 6 January).

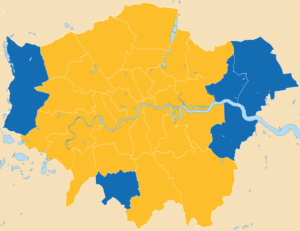

Steve rightly recognises London’s looming transport capacity problems – the sort of pressures that we already see in crazily overcrowded tubes and commuter rail services, which will get far worse as the city’s population nudges 10 million towards the end of the next decade. Where I differ with Steve is that I continue to see Crossrail 2 – which would link the national rail networks in Surrey and Hertfordshire with tunnels under London between Wimbledon in the south and Tottenham Hale and New Southgate in the north – as the first best solution to this capacity crunch.

Steve points out various local problems with some of the plans, including in Wimbledon and Balham. More important, he thinks it’s too expensive and instead suggests “much more affordable improvements”, such as the planned Bakerloo Line Extension.

Let’s deal with those local issues first. Steve is quite right to highlight some of the problem areas on the Crossrail 2 route, as set out at the last public consultation in 2015. Every project has its tricky local hotspots, which require extensive local consultation and detailed technical work to address. The good news is that the Crossrail 2 team have done this work and now have vastly improved proposals for key sections of the route, such as a choice between Balham and Tooting as a stop, and by looking at what Crossrail 2 means to Wimbledon town centre. The bad news is that local communities in these areas are none the wiser about proposed changes, and will remain in the dark until the Department for Transport agrees to Transport for London publishing revised plans. This must be a priority for 2019.

That leaves the wider strategic case for Crossrail 2 – and I my view that is stronger than ever. Crossrail 2 is a radical solution: rather than tackling a clutch of problems piecemeal, it brings the solution to them together. It will relieve the chronic congestion on the south west main line into Waterloo. It will relieve crowding on the Tube, especially on the Northern Line in south London. It will stem the rising numbers of regular station closures due to overcrowding, which are forecast to become steadily more numerous. It will cut congestion on the great eastern line into Liverpool Street. And it will ensure that passengers arriving on HS2 will actually be able to get on the Underground at Euston, rather than creating a giant bottleneck.

In total Crossrail 2 will increase the city’s rail capacity by around 10 per cent, bringing an additional 270,000 into Central London each morning peak time. And at the same time, it will deliver a huge boost for housing. The railway is deliberately routed through some of the parts of north-east London most desperately in need of regeneration, in Enfield’s Upper Lee Valley. Crossrail 2 will support tens of thousands of new homes there, making those areas attractive to develop where at present their very poor transport services prevent that. Altogether, it will support the building of some 200,000 new homes across London and the South East.

Certainly, Crossrail 2 is an expensive project, estimated to cost up to £30 billion. But it will generate benefits to the wider economy worth many times that amount. London’s experience with Crossrail 1 demonstrated the potential to secure funding contributions from a range of beneficiaries beyond just the hard-pressed taxpayer, which to some extent can be replicated by Crossrail 2. The joint DfT-GLA Independent Affordability Review on Crossrail 2, which I supported through its advisory panel, identified a wide range of potential funding and financing options, as well as promising scope to reduce and reprofile costs. Our report is with the Mayor and ministers awaiting a response.

There’s no doubt that the delays and cost overruns on Crossrail 1 make the near-term funding challenge for Crossrail 2 a degree harder. It would be naïve to pretend otherwise. Short-term progress may, as a result, be slower than supporters had previously hoped. But what London’s – indeed Britain’s – infrastructure now needs is a plan for the long term – one that looks decades ahead, not just a couple of years.

Thankfully, we have been given the blueprint for just such a plan by the independent National Infrastructure Commission, which published its plan for Britain’s infrastructure through to 2050 just last year. This backed Crossrail 2 as an essential and affordable component of a UK-wide investment programme, alongside other vital schemes such as Northern Powerhouse Rail, which will connect some of our great northern cities. Crossrail 2 will stop our capital from grinding to a halt. Both projects will drive growth and productivity and benefit the whole of the UK economy. The government now needs to set out a long term plan that commits to both.

Crossrail 2 is a grand and ambitious infrastructure scheme, as befits Europe’s largest and most dynamic city and the economic heart of the UK. It remains the right solution for London’s future. If we duck the decision now, we will deeply regret it in the 2030s.

David Leam is Executive Director, Infrastructure at leading business organisation London First, which is strongly supportive of Crossrail 2. More on that here.