When bus passengers are asked about their priorities, reliability always comes top. The reasons are obvious: commuting time to work, parenting commitments, meeting friends, hospital appointments or getting to school. Knowing a bus will arrive regularly and that you will reach your destination in a reasonable time is fundamental to travel choice, if you have one.

So when I read a Transport for London poster at Dalston Kingsland station recently, with its message about bus journeys “getting brighter”, it angered me enough to refer it to the Advertising Standards Authority. The poster may be cleverly worded, but it isn’t truthful. You have to go back to the early years of this century to find bus reliability figures as bad as they are now.

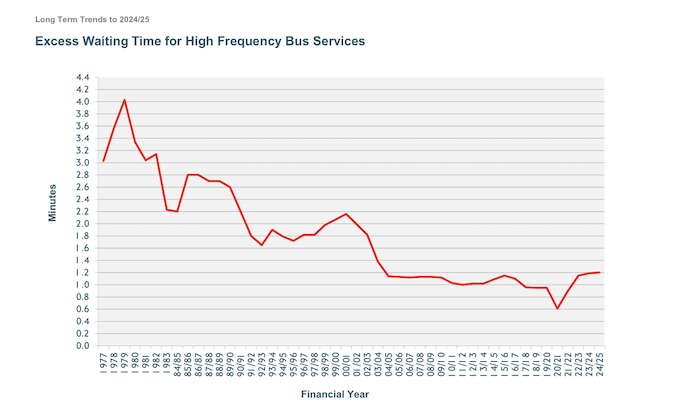

Transport for London was established in 2000 and very soon was incredibly proud of what it achieved for bus passengers in a remarkably short space of time. The chart below of “excess waiting time” dramatically demonstrates the improvements in reliability between the late 1990s and early 2000s. This was delivered initially by an active Government Office for London and then by TfL itself. The average amount of time London bus passengers had to wait beyond the scheduled period was halved.

The first Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, understood what mattered to bus passengers and focussed TfL’s attention accordingly. He used a mix of measures to achieve this aim, both physical and financial. At the heart of his policies was the so called “quality incentive contract”, a combination of bonuses and penalties for bus operators to run their contracted bus mileage, and to do so reliably.

Primary amongst the other measures was the London bus initiative, which introduced over 200 bus priority lanes across the city and, crucially, enforced them with cameras. Oyster ticketing reduced boarding times. And, of course, congestion charging was the most effective area-wide method for increasing bus priority. The funding from scheme was directed towards new and better services.

The improvement continued in the early years of Boris Johnson’s time as Mayor, maintaining a golden era for bus passengers, with more frequent services, more routes and route extensions. Passenger levels rose rapidly to 6.5 million journeys a day.

But his good work didn’t last. A second round of bus priority and a second new contract regime to incentivise quality of service were abandoned and the western extension of the congestion charge zone was removed. And in his second term, from 2012, Johnson appointed Andrew Gilligan, a journalist friend and fanatical cyclist, as his “cycling czar”.

The focus of London streets policy turned dramatically from tackling congestion and further enhancing London’s most important passenger service, the bus, to London’s smallest private transport mode, the bicycle. Cycle Superhighways and mini-Hollands consumed much of TfL’s energy and eye-watering sums of money for the next four years. Bus lanes were converted to cycle tracks and motor vehicle capacity was reduced in favour of cycle priority.

With massive amounts of disruption due to road works, the loss of bus lanes and overall motor vehicle capacity at key junctions across inner London, the inevitable occurred – bus journey times got longer. TfL and the bus operators did their bit to maintain performance by adjusting traffic lights to favour buses, shortening bus routes and improving their control of services. TfL officers undertook a lot of work to establish that a decline in passenger numbers was linked to slower bus speeds.

Sir Sadiq Khan’s mayoralty carried on where Johnson’s left off. A new cycling and walking commissioner, Will Norman, continued Gilligan’s focus on bicycles, this time under the cover of a “healthy streets” agenda. There has lately been some recognition of the damage being done to the bus service – hence the poster. But there are inherent contradictions: part of TfL is putting in bus lanes and other bus priority measures, while another part is taking out bus priority and removing motor capacity from bus routes in favour of cyclists.

As a result, bus service performance is the worst it has been since Livingstone’s first term. Reliability is worsening, as shown in the chart. Bus speeds are the slowest they have since the reporting mechanisms of TfL’s I bus system were introduced in 2013. TfL have missed their bus journey time target for the last three years, despite that target being slackened. And what of the actions the poster describes for making bus journeys “brighter”?

A plan published in 2022 promised to adjust traffic signal timings, add bus lanes and increase the hours of operation. These are good things to be doing. However, the root of the problem is that whilst there may be policies supporting buses, London government has been, and continues to, be far too casual about bus performance. The scale of the effort to turn around the decline is woefully inadequate. There are neither the policies nor the commitment to do more. Bus journeys aren’t about to get brighter anytime soon.

Vincent Stops is a former Hackney councillor and lead member for transport who worked on streets policy for London Travelwatch, the capital’s official transport users’ watchdog, for over 20 years. Follow him on X/Twitter.

Spot on, Vincent. And London is becoming untenable for the elderly and disabled due to the privileging of cycling above all else.

I have been in my car on Green Lanes where there is what used to be a bus lane converted into a wide cycle lane – but not quite wide enough for buses. The traffic has been stationery both ways, so there was nowhere for any traffic to get past. An ambulance and a fire engine with their emergency lights and sirens joined the queue. Drivers became distressed as there was nowhere for them to move across for the emergency vehicles to get through.

We sat there for about seven minutes before the queue of traffic moved sufficiently for some of the vehicles to mount the pavements in order for the emergency vehicles to pass. I thought, as I pondered the Mayor’s disastrous, ill-informed plan, that it mattered not if you were burning to death or dying of a heart attack, as long as the cyclists had room to meander along their designated wide lane.

That’s not all. I am frequently nearly run over by cyclists going through red lights or cycling on the pavements, yet there is no legal censure of this as there is for motorists and, indeed, pedestrians who endanger others by reckless jaywalking etc.

And another thing! Those of us who live in social housing neighbourhoods are being poisoned by the vehicles that used to take the ‘short-cuts’ before the LTN barriers that make some streets pollution free by restricting access and directing the pollution to the lower social economic areas to poison the poor instead.

Lastly, due to this catastrophic lack of sense in the ‘planning’ of the LTNs, it appears that those who instigated this have shares in the petrol companies. As drivers, we now have to drive for four miles where the journey used to be one mile, and disabled drivers cannot go out if they find it intolerable to sit in a vehicle for what can now be hours to travel a mile or so.

As the icing on this cake – today I had to travel the 2.7 miles between Newington Green and the Old Bailey to do my jury duty. I waited 30 minutes for the 341 that then tookand hour and five minutes to get to Farringdon.

Coming home I waited for 10 minutes at Farringdon, walked to Rosebery Avenue in frustration with the constantly changing and unreliable notification on the LED displays, waited another 20 minutes, gave up on the 341 and got the 38 to Balls Pond Road, which meant then walking twice the distance I would have had there been a 341 come within the published schedule.

Sadiq Khan needs to be voted out of office and any ‘honour’ revoked.

Here in Penn Road, Lower Holloway, we have benefited from new zebra crossings at each end of the road and some good quality paving and street furniture. We are also now on a two-way cycle route which allows cyclists to go against the one-way vehicle traffic. But usage is pretty low – maybe 100 riders an hour at peak times. I would be interested to know what the return on investment is.

Great Article.

May I suggest also complaining about TfL’s strapline too, which is “Every journey matters”. That is manifestly untrue for anyone in a motor vehicle, because TfL’s approach is to make motoring slower, more difficult and more expensive.

I would offer the following. Bus service reliability is not just about punctuality. At the present, it seems to me that not enough is done by central Government to improve the service.

There needs to be a policy of prioritisation of public transport. Bus lanes are a good idea, but what about stiffer penalties for obstructing them? A lot of selfish (car) driving impedes public transport. Give priority to buses, make it statutory on any roads, and when pulling away from request stops.

The driving public need to be persuaded to use public transport. Tax road-users according to the potential wear and tear that vehicles produce: long vehicles, SUVs. Increase the road tax.

Private vehicles (including commercial transport) have always subsidised public transport. Let’s make that more clear, that it is a privilege, not a right, to drive on the roads, and the cost of that is to pay towards the cost of maintaining the physical condition of roads, and the free flow of traffic.

Thank you for your comments.

Yes I agree the London bus service is not good enough:

1. What happened to Bus ‘Priority’? Where are the bus priority lanes, 200 of them?

2. Why not print large posters on all buses warning road users to give way to buses, especially cyclists, scooters, vans, pedestrians, etc ?

3. Teach bus drivers not to give way to other vehicles, they have far more passengers and should get priority.

4. Abolish so call ‘floating bus stops’ and order cycles to stick to cycle lanes always.

5. Introduce Express buses which only stop at key stops like the Uxbridge Road, what about the A10?