Shabna Begum was born at Mile End Hospital in 1976, just a few weeks after her parents and their three-year-old daughter Rasna moved into a small, dilapidated house on Deal Street, a few hundred yards from Brick Lane. The family thought they were renting because they paid for and received a rent book from a “landlord”. In fact, the property belonged to Tower Hamlets Council and the landlord was a con artist. Begum aptly describes her family as “accidental squatters”.

This story sets the stage for a deft exploration of the Bengali squatting movement, which took root in the mid-1970s as a response to changes to Commonwealth immigration policy prompting women and children to migrate to the UK. The 1971 Immigration Act significantly altered entry conditions from work vouchers to family dependency, with profound consequences.

For many years, Spitalfields had been home to single Bengali men who eked out a living from low-paying jobs and lived in shared housing, frequently rotating beds in double or triple shifts. However, this hostel-style accommodation, which is still available in parts of Tower Hamlets, proved unsuitable for reunifying or new families, and finding suitable private or social housing was nearly impossible.

Inspired by the success of local countercultural groups, a small number of Bengalis – which grew into many more – took matters into their own hands. They began breaking into and establishing households in boarded-up slum properties in and around Spitalfields. Notably, Black Power activists of the Race Today collective in Railton Road, Brixton, such as Farrukh Dhondy, Darcus Howe and Mala Sen, provided crucial ideological support and legal advice.

Begum’s concern that this episode of squatting in Bengali history in the UK has received little attention is well-founded. In particular, she discovered that the archives were lacking in acknowledging women’s contributions to the cause. Because of this scarcity of insider accounts, she, with excerpts of conversations with her parents carefully considered, conducted oral history interviews with former Bengali squatters (she prefers the term Bengali to Bangladeshi). After interviewing over 40 male and female participants in both Bengali and English, she realised that the Bengali squatters exhibited diversity within their ranks.

Begum, the Runnymede Trust’s current interim co-CEO, discovered that while some were proud of their activism, others felt ashamed as it seemed to contradict their cultural values of honour and respectability, both in their homeland and in the diaspora setting. But what all squatters had in common was a history of instances of street racism, perpetrated not only by members of the far-right National Front but also by white neighbours, who saw Bengalis as not belonging to the “real” East End, which was imagined as “essentially and rightfully white”. To make matters worse, these white neighbours viewed Bengalis, because of deliberately propagated colonial myths, as culturally inferior and primitive, and men, in particular, as passive and effeminate.

For an insightful chapter on Sylhet and how Sylheti Bengalis came to settle in the East End, Begum draws on available historical material from a variety of sources, including the writings of locally-based activists Caroline Adams and Charlie Forman, as well as academics such as social anthropologist Katy Gardner and historian Rozina Visram.

We learn that in the 1970s the Greater London Council owned approximately 31,000 homes in Tower Hamlets and the local authority, almost 18,000. Yet waiting list rules based on residency and other factors discriminated against Bengali migrant families. In addition, white housing officers who had considerable latitude in interpreting those rules, further blocked Bengali families from gaining access to suitable social housing. And given the pattern of horrific racial violence and harassment present on many of Tower Hamlets’ all-white housing estates, it’s no surprise to learn that families often preferred to live in or near Brick Lane in the borough’s west anyway.

This groundbreaking book introduces us to some extraordinary individuals, including Jalal Rajonuddin. In 1972, shortly after Bangladesh gained independence from West Pakistan, Jalal, then 12 years old, travelled with his family from Sylhet to Birmingham before settling in Tower Hamlets. A few years later, in the absence of action from the local police, Jalal, a co-founder of the Bangladesh Youth Movement (BYM), organised nightly vigilante groups to protect Bengali households from attack. He also had direct experience of racial violence, as did almost every male his age. Caroline Adams once discovered him unconscious after being attacked by a group of white boys at a funfair in Shadwell.

Another person we encounter is Husnara, who had four daughters when she began squatting. Using a transnational lens, she compares the efforts of women in making squatted premises habitable while also serving as meeting and dining spaces for male activists to the role women played supporting jungle-based freedom fighters during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Husanara modestly describes this as “work you might not see”. But her life story illustrates the significance of women’s domestic roles and traditional gender expectations within east London’s Bengali community. Indeed, Begum claims this domestic work was crucial – without it, the squatting movement, centred on curry cafes on Brick Lane, would have struggled to gain traction.

In the final chapter, titled “Tower Hamlets is not a place you live forever”, Begum reflects on how British Bengali identity continues to change. She cites the sale of properties owned by Bengalis, purchased under the Right to Buy scheme, and the migration of thousands to neighbouring London boroughs such as Newham and Redbridge and to Essex, in the search for family-friendly houses with gardens. Interestingly, some of these vacated properties are now occupied by well-educated (mainly non-Sylheti) Bangladeshis who, before the Brexit drawbridge came up, migrated from Italy, Portugal and Spain (where they hold citizenship) in search of a better future for their children.

Begum also addresses the persistent levels of deprivation in Tower Hamlets and its links to structural and institutional racism. She makes two specific points in relation to housing. Firstly, the borough, which is home to the largest Bangladeshi community in the UK, continues to struggle with overcrowding and a long waiting list for affordable social housing. Secondly, overcrowded housing, along with employment in hard-hit sectors like hospitality and transportation (including taxi driving), has contributed to the disproportionate number of Covid-19 deaths among Bangladeshis.

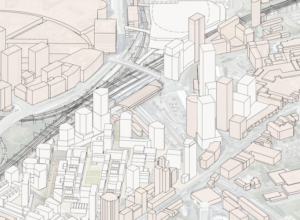

Not surprisingly, Begum discusses the ongoing Save Brick Lane campaign, led by British-Bengali activists who oppose a proposed development on the Old Truman Brewery site. The site is owned by the Zeloof Partnership, a business founded by a Jewish family of Baghdadhi roots formerly involved in the local garment trade. The plans call for the conversion of a parking lot near the northern end of the row of curry restaurants and cafes into offices, a shopping mall and a restaurant space. Significantly, the digitally savvy activists, who are young and middle-class with ties to the neighbourhood but do not live there, are inspired by the Bengali squatter movement of the 1970s.

The activists correctly assert that Bengali Brick Lane has social, cultural and economic significance beyond its historic association as the UK’s one-time “curry capital”. Local politicians, they believe, are allowing gentrification by default, by neglecting the area. However, Begum also found that not all locals oppose the Truman Brewery plans – some curry restaurant owners support them, believing the development will increase footfall and boost turnover for their businesses at a time when turnover has declined, largely because many City workers are now working from home.

While acknowledging the inherent difficulties of documenting complex social histories, Begum’s work is invaluable. Her informative and thought-provoking book provides a solid foundation for future scholarship by compiling important but often overlooked narratives. It encourages further investigation into this significant but little-known movement. And, most importantly, Begum’s story brings to life people who bravely fought for security and belonging in east London.

From Sylhet to Spitalfields is published by Lawrence and Wishart Limited (£16 paperback). Buy it HERE.

Seán Carey is a senior research fellow in the School of Social Sciences and a member of the Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CODE) at the University of Manchester. An earlier version of this review was published in the Oral History Journal. Follow Seán on X/Twitter. Image from the book’s cover.