Cornhill is the centre of gravity of London’s historic financial district and one of the three ancient hills of London, the others being Ludgate Hill and Tower Hill. As its name suggests, corn was once traded there. The three hills are not as famous as the Seven Hills of Rome, and it requires an act of faith to believe they even exist because, thanks to London’s constant growth, they are no longer in plain sight.

But what can still be seen on Cornhill itself are two remarkable Anglican churches, one dedicated to St Michael, the patron saint of France (above, left) and the other to St Peter (above, right). They have managed to escape the conquering needs of commerce, though you could easily walk past without noticing them. They are best seen by meandering into the time-warp of medieval alleyways behind them, where each has a small garden.

Thomas Gray, author of Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, was born in the area in 1716 and lived nearby. The font at St Michael’s used for his baptism is still there today. It is at least possible that its churchyard was in the back of his mind when he wrote his celebrated poem, believed to have been inspired by a church in Stoke Poges in Buckinghamshire.

Both churches consider themselves to be the oldest in London. St Michael’s has a fairly well authenticated claim to have been in existence at least since 1055, when it was recorded that a priest called Alnothus gave it to the Abbot of Evesham. In 1503, the patronage, as it is known, passed to the Drapers’ livery company, which has retained it ever since.

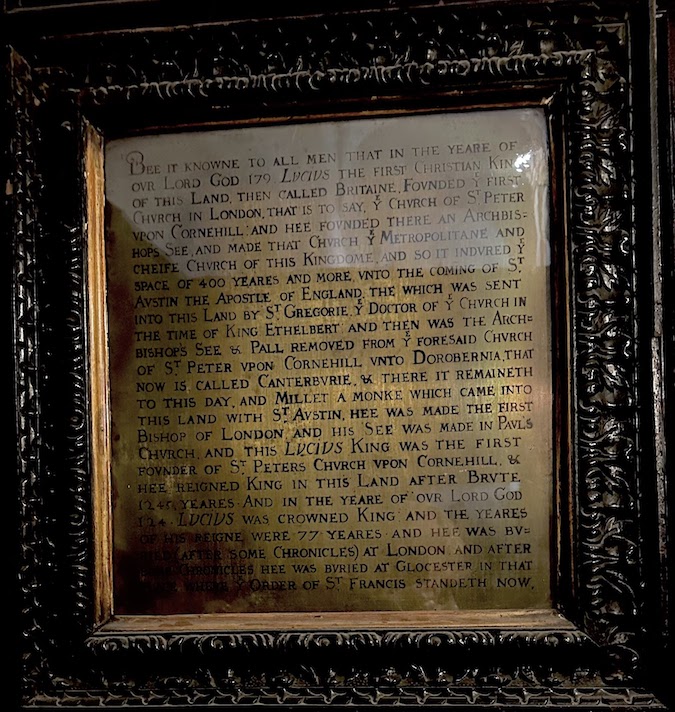

However, St Peter-upon-Cornhill, to give it its full name, says “it is widely held” that there has been a Christian place of worship on its site since the year 179 and that the original one was “founded as the first church in London” by King Lucius who, according to a long standing but contested belief, was the first Christian King of England. A tabula or brass plate (below) on the wall in an antechamber of today’s St Peter’s, designed by Christopher Wren, appears to endorse this.

However, in his thorough examination of the matter, archeologist John Clark of the Museum of London says the the tabula can only be traced back to 1400 at the earliest. He adds: “We cannot accept that St Peter’s was truly established as a cathedral by a real (as opposed to legendary) King Lucius in the 2nd century AD. But we can accept the possibility that Londoners as early as the 12th century believed it was the most ancient church in the city.”

There are other claims to be London’s oldest church, such as that of St Pancras Old Church, which says it has been a “site of prayer and meditation since 314 AD”. This contest looks set to go on and on, like the one to be recognised as London’s oldest inn.

St Peter-upon-Cornhill and St Michael’s share an unusual heritage. Both were Roman Catholic churches until after Henry VIII’s break with Rome and both were built on top of the ruins of the huge Roman Forum and Basilica in Londinium, walls from which have been regularly excavated by archaeologists.

Each can therefore say they have been “Roman” in terms of both religious heritage and of geographical location. The are shown as they were in 1647 on the far of the Wenceslaus Hollar engraving below.

The Reformation was a traumatic event for the two churches and St Michael‘s has left us a graphic record of what actually happened when it had to change from Catholic to Protestant and back again under the governance of Henry VIII, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Archaeologist John Schofield in his book The Building of London lists “the almost farcical experience of the churchwardens of St Michael’s”, one of the richest churches in the City. In 1548 they had to pay masons to demolish stones representing saints and the Virgin Mary. Church plate had to go as did the confessional and vestments, brasses, embroidered images and the altar stone. “Inside three years the old religion had been overturned and the church disembowelled,” Schofield notes.

When Mary, a devout not to say overzealous Catholic, known to Protestants as “Bloody Mary” became Queen in 1553 everything was reversed. Back came candles, holy water, hymnals, mass books, chalices, a wooden statue of St Michael and two thousand bricks to reconstruct part of the inside. By 1557, when it had just been restored to something like its former splendour, Mary died and the accession of Elizabeth brought another about-face. The church had to be cleansed again of its associations with Catholicism.

All this was nothing compared with the destruction caused by the Great Fire of London in 1666 which started a few hundred yards away in Pudding Lane. This led to the reconstruction by Wren’s office and to the churches we see today. The remarkable thing is that after all those centuries they are still there. If you are in the garden of either building, both very much working churches, you are in the nearest experience you will get to medieval London anywhere in the City.

This is the eighteenth article in a series of 20 by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in the Eastern City part of the City of London kindly supported by EC BID, which serves that area. All the previous articles are here. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.