This is the tale of the son of a tanner who went to London and wrote celebrated poetry and plays and regularly returned to his native Warwickshire. He also acquired a share in a playhouse and is memorialised in Westminster Abbey. Meet not William Shakespeare, whose biography is so similar, but his contemporary Michael Drayton.

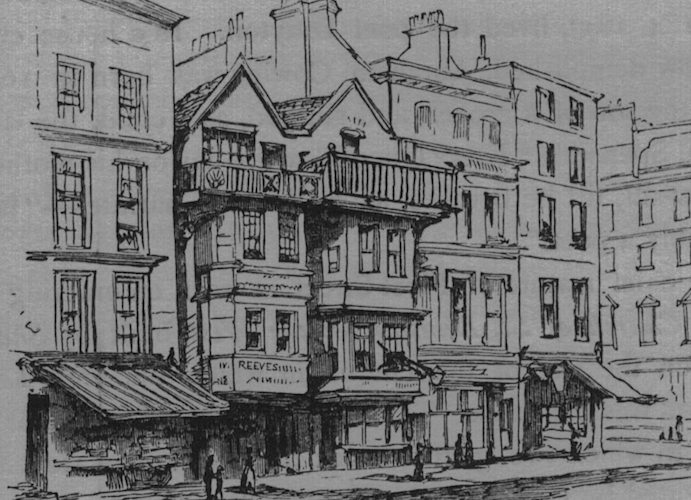

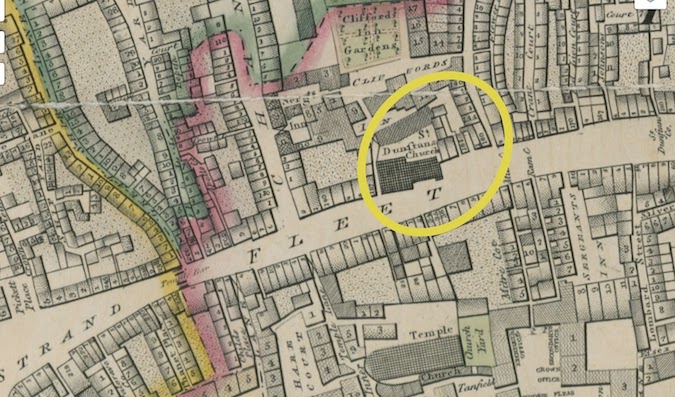

Drayton is little known today, but in his time he was a rival to Shakespeare and almost as celebrated. He lived in Fleet Street between St Dunstan’s church and the turnoff to Fetter Lane (pictured above), not far from where Izaac Walton, author of The Compleat Angler, resided. His house was also close to the theatre he invested in, which formed part of the Whitefriars monastery building between Fleet Street and the Thames, some of which is still visible .

At the National Portrait Gallery there are usually paintings of Shakespeare, Jonson and Drayton displayed close together. Drayton is the one with laurels around his head, a recognition that he was once a contender for the then unofficial role of poet laureate.

William Drummond, a friend of Jonson, said Drayton would “live by all likelihead so long as … men speak English.” One of my favourite lines of his is: “Since there’s no helpe, come let us kiss and part” – a mini-story in a sentence.

Drayton was nothing if not prolific. As well as voluminous poems, he co-wrote around 20 plays but, unlike Shakespeare’s canon, most of them are lost. The only surviving play to which he contributed is about the medieval solider and leader of the Lollards, Sir John Oldcastle. For a while wrongly published under Shakespeare’s name, it was written as a riposte to an unflattering portrayal of Oldcastle in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1 (This also offended one of Oldcastle’s influential descendants, which forced Shakespeare to change Oldcastle’s name to John Falstaff). Meghan C. Andrews, writing in the Shakespeare Quarterly, suggests that five or six of the plays Drayton was involved in were “direct responses to or influenced by Shakespeare’s work”.

Drayton’s magnum opus, Poly-Olbion, is one of the most extraordinary poems in the English language. That is partly because of its length (15,000 lines in iambic pentameter), partly because of how long it took to write (30 years), and partly because of the subject matter. It is a topographical epic about the history of England and Wales, which E M Forster called an “incomparable poem”. Drayton began this Herculean task around 1598, when Shakespeare was in full flow. The poem may be about to get a reappraisal. Exeter University has been involved in a major study of Poly-Olbion, to be published in a year or so.

On December 23, 1631, Drayton died at his Fleet Street home almost penniless, his form of pastoral poetry having gone out of fashion. Yet he was so highly regarded by his contemporaries that, according to the antiquary William Fulman: “The Gentlemen of the Four Innes of Court and others of note about the Town, attended his body to Westminster.” He was buried in Westminster Abbey next to a plaque of Ben Jonson (whose actual body is buried standing up elsewhere in the building).

Insofar as Drayton is remembered at all today, it is because of a reported binge drinking session with Shakespeare and Jonson at a tavern in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1616, as a result of which Shakespeare is said to have died. Few people have taken this story seriously, as it is based on remarks made by the local parish priest over 40 years after Shakespeare’s death, albeit when some of his contemporaries were still alive.

Perhaps, then, they were unreliable recollections. But I have reached the age where although I have difficulty remembering what happened 10 minutes ago, I can much more clearly recall events 40 or 50 years in the past. I rest my case.

All previous instalments of Vic Keegan’s Lost London can be found here and a book containing many of them can be bought here. Follow Vic on Twitter.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for just £5 a month. You will even get things for your money. Details here.