Last month, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) released its calculation that inner London borough councils were lined up to be the biggest losers from the Fair Funding Review 2.0, the government’s process for changing how money for local government will be allocated across England from next year.

Alarmingly, it estimated that some of the capital’s boroughs would “see funding fall by over a quarter if the reforms were introduced immediately”. Even if they increased their Council Tax levels by the highest amounts permitted over the next three years they would still, the IFS said, “face a real terms cut of 11-12%” despite a floor to limit losses.

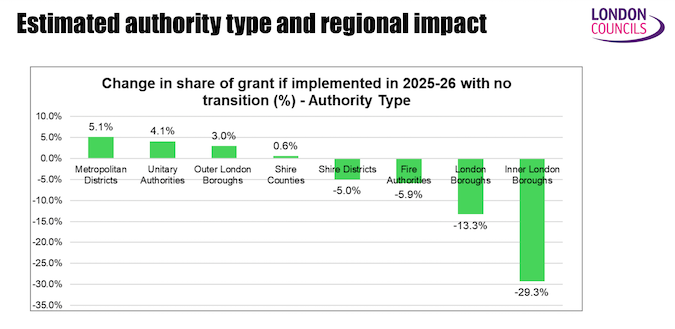

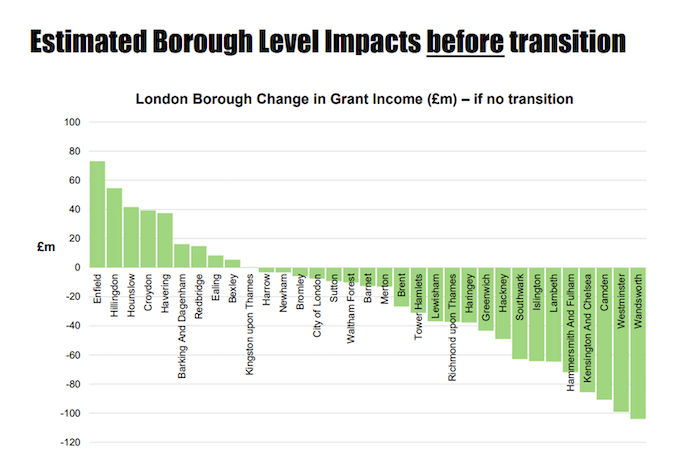

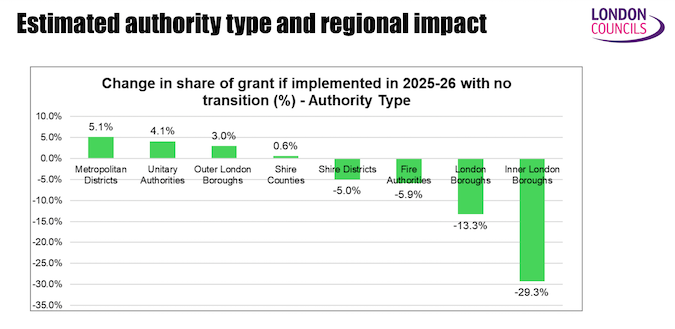

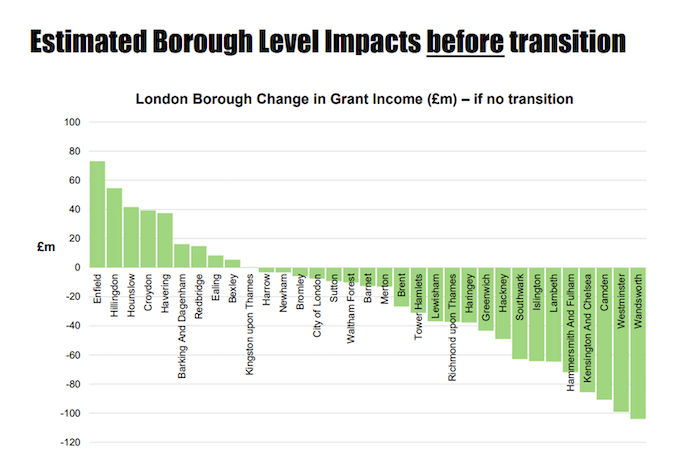

As a region, Greater London would be hit harder than any other, with the East Midlands and Yorkshire & The Humber doing best, though that wouldn’t be the whole London story. Further analysis has taken place, including by London Councils, the cross-party body representing all of the capital’s local authorities. These efforts indicate that some boroughs would fare relatively well under the proposed new formula, all of them in outer London, as the London Councils graphs below show.

Among the winners would be Hillingdon, Havering, Hounslow, Enfield and Croydon. But more than 20 of the 32 boroughs would be worse off, with Camden, Hammersmith & Fulham, Kensington & Chelsea, Westminster and Wandsworth the most heavily clobbered.

London Councils warned the government a year ago that many boroughs were facing a funding crisis. In June, it stressed the importance of the funding reforms recognising London’s pressing social problems, and last month produced a briefing arguing that the review proposals “will fail to produce a robust, long-term funding system that genuinely matches resource to need” and land more boroughs in deep financial trouble. Already, seven of them have had to seek extra financial support.

How has the government, specifically the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, come up with its new Fair Funding formula? Is it fair to London? And what could it mean for Londoners?

*

The main purpose of the Fair Funding Review is to allocate a bunch of grants to local government in a new way, essentially by simplifying them and distributing them according to new set of formulae the government regards as being fairer. London Councils thinks that, as things stands, the boroughs would collectively receive £700 million less than they do at present.

It is, perhaps, not widely known that the largest proportions of local authority spending go on adult and children’s social care, which are among the services councils must provide by law. The more visible to most of us are things like rubbish collection, road repairs and street cleaning. The Fair Funding proposals as first set out envisage redistributing existing total funding for England to help poorer areas more. The worry is that its calculations fail to recognise the levels of poverty and need in London.

Councils also raise funds locally, of course. An Institute for Government explainer from five years ago said just over half the funding for local government in England comes from Council Tax and just over a quarter from the portion of Business Rates they are allowed to retain. That left 22 per cent from government grants. The government’s proposals raise the possibility of many Londoners having to pay more in Council Tax and see cuts in services too, as boroughs struggle to balance their budgets.

Another part of the national context is that local authority revenues as a whole fell substantially under the austerity policies of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government before partially recovering from 2017/18. Between 2009/10 and 2019/20, the government grant element was cut by an astounding 40 per cent in real terms, the Institute’s explainer says, before recovering a bit during the pandemic. Throughout, the proportion accounted for by Council Tax has risen.

The austerity period hit inner London boroughs particularly hard. In 2019, Centre for London analysis put Westminster, Newham, Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Camden and Wandsworth at the top of the list. The then chair of London Councils, Peter John, said government funding for the boroughs had dropped by 63 per cent since 2010. And now, under Labour, the axe is out for London again.

The government’s approach, which dates back to pre-Covid, has been to make a calculation about the amount of need that exists in each local authority area compared with all the others, and another one about the resources at that local authority’s disposal, which largely comes down to the amount of Council Tax it can raise. The difference between the two is the basis for deciding how much grant the government should bestow.

London’s beef is with the way the “relative needs” assessment has been calculated. This has involved boiling down about 15 different formulae for each local authority into seven main ones and, rather than ring-fencing the different grants as before, pouring them all into one pot. The seven areas covered are adult social care (the largest), children’s services (the second largest), a “foundation formula” element derived from population and deprivation figures, homelessness, road maintenance, fire and rescue provision and home-to-school transport.

It’s a mathematical equation for working out who gets what that generates bad results for most of London. It’s also very complicated – the document explaining how it’s done is around 120 pages long plus ten annexes. A lot of is drawn from its now rather outdated Indices of Deprivation, which haven’t been revised since 2019 and were based on the findings of the 2011 Census. The formula for children’s services has its own deprivation index, which also comes into the calculation.

Because these reforms have been a long time coming, London government has been able to anticipate some of what is proposed. That is just as well, because national government has not attached any figures of its own to the impacts of its changes. That makes it much harder to respond to them with precision. Doing so has entailed working with specialist consultants and modelling the impacts as well as possible. No one has a definitive answer. The broad direction of travel, though, seems pretty clear.

*

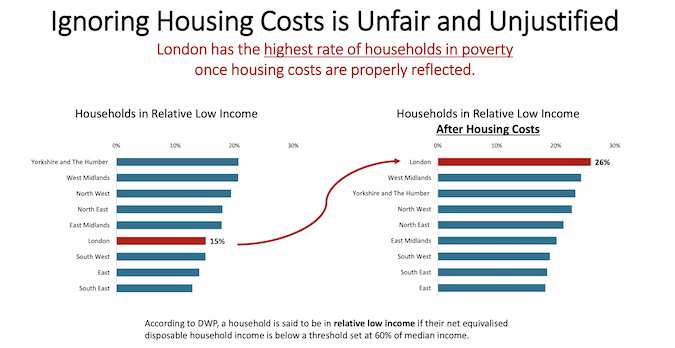

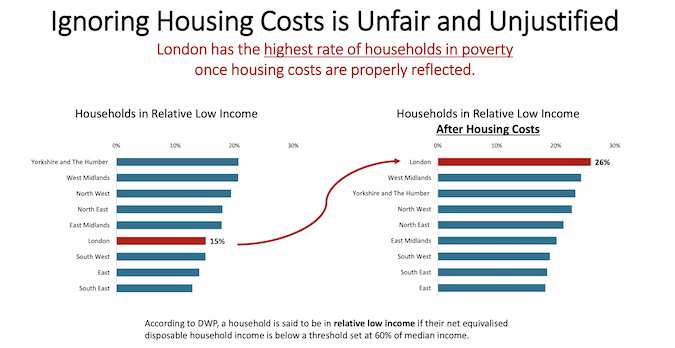

What will happen next? London government, which includes Sir Sadiq Khan, has been arguing for adjustments. There has been, it’s fair to say, some amazement that housing costs were not factored in. As the London Councils chart below shows, it is these that push Londoners whose incomes might be quite good compared with counterparts elsewhere into the “in poverty” category, which in London is very large – the city’s poverty rates are the country’s highest. The word is that there might be some movement on the housing front, but nothing has yet been confirmed.

The children’s services formula is causing particular concern and seen as the most consequential change in the Fair Funding Review as a whole. It leaves every London borough except one worse off in that department, and the exception only just.

A multi-level regression model has been assembled. Devised by the Department for Education under the last government, it uses a number of socioeconomic datasets to predict the needs of local school students. Its final evaluation report is 200 pages long and enough to make the most accomplished number cruncher weep. Long story short, a top drawer team assembled to divine its meaning concluded that this “whole new approach” wasn’t very good.

Overtures have had a hearing, a ministry technical working group has been formed and, again, progress is being made with recognising some of London’s distinctive social characteristics. These again include housing and also the free school meals situation which, in London, already has a universal element, thanks to Mayor Khan’s high-profile Londonwide initiative. Eligibility for Universal Credit has been suggested as a better metric.

Measuring children’s health was identified as another tricky area, and not only in terms of what it meant for London. The review relied on responses to the 2021 Census, in which a question asked parents only if their child was in general good health or not. Hardly any – about two per cent nationally – ticked the “bad health” box.Then there are the effects of household overcrowding. Past studies have demonstrated a link between it and the likelihood of children ending up in care. Yet somehow the new model points to the opposite.

Among the vaguer elements is a “remoteness factor” which was presented in the review as an adjustment based purely on theory, together with a request for supporting evidence. It supposes that access to any kind of service, product or amenity will be easier and cheaper if you live in an urban area than a remote one, solely on the basis of proximity. This has induced significant annoyance, not least because other government research has shown that the theory doesn’t hold up.

Does the Fair Funding model work properly? Are its mechanisms muddled? Are its ingredients sound? Are its potential outcomes actually fair at all?

*

The process continues. There is lot at stake. It has been estimated that the children’s services formula alone, if left in its initial form, would see £1.5 billion go out of London. The deprivation measures, the free school meals and the omission of housing costs in their own right also seem to have the potential to leave Londoners in need of local council support worse off. London is also pushing back on the overall population numbers the review relies on. These are drawn from the last Census, which was conducted when many Londoners left the city temporarily because of the pandemic and could therefore be artificially low.

There’s acknowledgment that the outgoing funding mechanism has in some ways, favoured London: for example, it factors in ethnicity, especially of black groups, as a proxy for higher need, and has historically enabled Westminster, Wandsworth and Kensington & Chelsea, all of them Tory strongholds until two turned Labour in 2022, to set very low Council Tax rates.

At the same time, the new formulae overall seem to effect London as a whole so negatively that there is an urgent need to understand them better and figure out why that might be. The government’s consultation period is over, but that work is still ongoing with London concentrating particularly hard on children’s services and housing costs. In the midst of this uncertainty, boroughs are trying to plan their budgets. the uncertainty isn’t helping.

A formal government response to the feedback to its consultation is expected to be published next month and a policy statement from the department, now headed by Steve Reed, at around the same time, perhaps the same day. The final outcome of the Fair Funding Review 2.0 will not be known until the provisional local government finance settlement comes out in December, following the budget late the preceding month. Fingers crossed.

Follow Dave Hill on Bluesky. Photo from Greater London Authority.

OnLondon.co.uk provides unique coverage of the capital’s politics, development and culture with no paywall and no ads. Nearly all its income comes from individual supporters. For £5 a month or £50 a year they receive in-depth newsletters and London event offers. Pay via any Support link on the website or by becoming a paying subscriber to publisher and editor Dave Hill’s Substack.