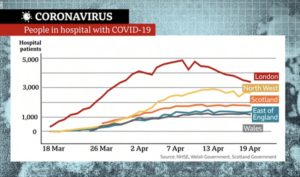

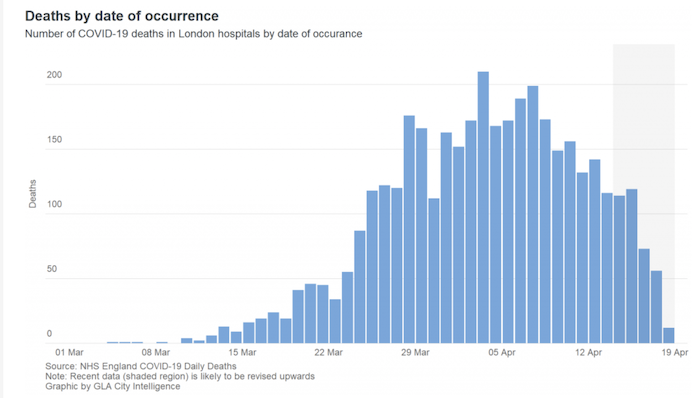

As London leads the UK towards its coronavirus infection peak – in the week ending 3 April registering 62 per cent more deaths than the previous weekly record – radical steps have been taken to help the NHS in the capital deal with the pressures. The most visible is the first 4,000-bed NHS Nightingale hospital, which has risen from nothing in the ExCeL exhibition centre at Custom House in Newham. Much more impactful have been huge increases in the capacity of the intensive care units of the capital’s acute care hospitals and much elective treatment – non-emergency surgery planned in advance – being suspended. Powers to purchase use of private hospital beds for NHS patients have been temporarily centralised and, in an extension of a long-planned move, health secretary Matt Hancock has wiped £3.1 billion of debt off London’s NHS trusts.

The extreme demands made by Covid-19 have come during the latest transitional period in the complex organisation of the NHS nationally, London very much included. The virus has further delayed the government’s implementation framework for its NHS Long Term Plan, a 10-year vision, published in January 2019. This has been pushed back to the autumn, with knock-on effects on associated re-organisations. With the spotlight trained so firmly on the NHS just now, this seems a good moment to look at how this cherished institution functions in London and the key issues it was already facing for the future.

Organisation and funding

About 16 per cent of England’s population lives in Greater London, which receives roughly 20 per cent of the country’s total NHS spending. The disparity is due mostly to there being so many specialist services in the capital for patients from far and wide, and the range of needs arising from the capital’s population being so diverse.

London’s NHS funding feeds into and moves between a bewildering array of different organisations. Several have impenetrable names and the language used to describe what they do can be confusing. One way to start making sense of it all is to follow the flows of NHS funds in England as a whole and in London in particular.

All NHS money begins its journey from the Department of Health & Social Care and about three quarters goes to a division of it called NHS England, created in 2012. This was intended to be a small organisation but has become a dominant one, employing more than 4,000 people. It has seven regional teams, including NHS England London, which has more than £15 billion at its disposal to distribute.

****

The bulk of this money goes to bodies called Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). These are made up of General Practitioners (GPs) within defined local areas, and their governing bodies also have nurses, hospital consultants, patient representatives and sometimes people from local authorities sitting on them. The job of CCGs is to plan and monitor local health and care services and also “commission” them, which means deciding how the money at their disposal is spent on services they think patients in their areas will need.

The concept of NHS commissioning was introduced in the early 1990s under reforms which, as influential health research charity The King’s Fund puts it, “separated the purchasing of services from their delivery, creating an ‘internal market’.” The argument went that making the service providers – hospitals and others – compete for money would foster greater efficiency and responsiveness, because GPs have closer day-to-day contact with patients. The funding of GP practices themselves is NHS England’s responsibility.

CCGs were introduced by the Health and Social Care Act 2012: a £3 billion shake-up “so big you could see it from outer space,” said then-NHS CEO David Nicholson, despite David Cameron having promised no top-down NHS reorganisation. Their multi-clinician boards are quite different from what coalition health secretary Andrew Lansley, who wanted to put money directly into the hands of GPs, imagined, and they have gone through various changes since. In London, there were 32 CCGs, each corresponding to a borough. But this month, 18 of them have merged into three much larger ones and a similar consolidation is planned for the remaining 14.

The “providers” from whom CCGs “commission” the most services are NHS trusts, which also emanate from the early 1990s “internal market” reforms. They are not actually trusts in the usual or legal senses, but public sector corporations that run health facilities and services, including dozens of London hospitals, ranging from the likes of large St Thomas’ in Waterloo where the Prime Minister was treated – administered in partnership with Guy’s at London Bridge – to small specialist ones, such as the Memorial Hospital in Woolwich or the Goodmayes in Redbridge.

****

To confuse matters further, there are formally two kinds of trust, the NHS Trust and the NHS Foundation Trust. Several are named after major hospitals they manage, such as Barts Health NHS Trust or the King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, though many run multiple health facilities and provide other services. Barts is running NHS Nightingale.

Nineteen trusts run “acute” hospitals, which means they provide active, short-term treatment for severe injuries or conditions in emergency departments, intensive care and other “high dependency units”. There are 10 mental health trusts and six “community” trusts, plus the London Ambulance Service trust. Some of the trusts have the word “university” in their title, denoting that they teach medical students and undertake research alongside providing care.

NHS Foundation Trusts were introduced from 2002. They were initially significantly more independent from the Department of Health than the already existing NHS Trusts, and controversial with some because they could function more like private businesses, for example by borrowing money for investment and even buying other hospitals. It can also be argued that they represent a kind of devolution in that they formed part of a continuing attempt to make health care more “patient-led” and responsive.

Three of the very first NHS Foundation Trusts were in London: Homerton University Hospital, Moorfields Eye Hospital and cancer specialist the Royal Marsden. All NHS Trusts were expected to attain NHS Foundation Trust status or become part of an existing one by 2014, but that hasn’t happened: the budgetary autonomy of the Foundation trusts has been watered down and the distinction between the two kinds of trust has eroded. In keeping with their convergence, the finances of both types of trust are now regulated by a single body called NHS Improvement, which is in the middle of merging with NHS England. The care provided by trusts is regulated by the Care Quality Commission.

Among London’s providers are multi-hospital trusts Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Barts Health NHS Trust, operating five or more institutions each and providing services to a 1.5 million and 2.6 million patient populations respectively. As well as the famous Royal Free Hospital in Hampstead, the Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust runs Barnet Hospital and Chase Farm Hospital, both of which it bought in 2014, plus clinics at Edgware Community Hospital, Finchley Memorial Hospital and North Middlesex University Hospital, which is run by a separate NHS Trust. It employs more than 9,000 staff and provides services to about a million patients.

A completely different type of NHS Foundation Trust is the Central and North West London, which doesn’t have any hospitals at all. It provides mental health services in Surrey and Milton Keynes as well as London. These include a health and wellbeing service for people affected by the Grenfell Tower fire.

The Darzi Review of London’s healthcare in 2007 recommended as much treatment as possible to be carried out locally, for a few hospitals be designated as major acute centres and for others to specialise. It had limited impact on London’s hospital provision. With the refinement of patient flow management practices, bed numbers in London hospitals have steadily declined in recent decades and acute hospitals now run very close to capacity.

Some London hospital trusts, such as King’s and Bart’s, run huge deficits, while some of their neighbours are in surplus, which can make collaborative working difficult. The debt write-off will relieve pressure on financially constrained trusts. Changes to hospitals’ payments regime and the commissioning process had been expected under the NHS Long Term Plan, and it’s too early to say how the coronavirus crisis might affect this.

****

Another kind of organisational healthcare unit in London (and the rest of England) is the local Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP). These were created in 2016 to bring local councils, which are responsible for social care, and NHS bodies together to run health and care systems in a more co-ordinated way. London has five of these, each covering a sub-region of the metropolis. The consolidated London’s CCGs, mentioned above, will align with them.

They are voluntary partnerships, not statutory bodies, and they came about to fill a vacuum in regional leadership after Strategic Health Authorities were abolished in 2012. They mark a shift away from competition. The watchword now is collaboration and there is a big push to promote healthy lifestyles and increase efficiency.

At the start, in a policy climate dominated by austerity, they were seen by some as opening the door to NHS England imposing financial targets on local areas. They had a fractious relationship with some local politicians. Sutton Council leader Ruth Dombey exposed the South West London STP’s plan to shut one of the area’s five acute hospitals. London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust put on hold plans to reduce acute beds after Ealing and Hammersmith & Fulham councils refused to support the STP.

For now, hospital closures are low on the agenda. STPs have bedded in and benefited recently from the appointment of four independent chairs from a variety of medical backgrounds and the arrival of new NHS England London CEO David Sloman. There remains a democratic deficit in STPs, with more local authority involvement at officer than at elected councillor level, although that is changing. There is a concern that as CCGs amalgamate, STPs will overshadow statutory local bodies concerned with community health, like Health and Wellbeing Boards.

Under the NHS Long Term Plan, STPs are to be superseded by April 2021 by an even more collaborative model called Integrated Care Systems (ICSs), but the timetable has been delayed by coronavirus. South East London STP has already made the transition to an ICS and the North and South West London ones are expected to follow shortly. In the NHS, little stays the same for long. A King’s Fund animated film makes a good job of explaining the English system as a whole.

Primary Care

Most peoples’ first point of contact with the NHS is their local GP practice doctor. There are some 7,000 GPs and 1,200 GP practices in London. Most GPs are independent sub-contractors to the NHS, though the proportion who are its employees has grown to around a third. The principle that we can all choose our GP has remained, with some striking consequences. Digital-first provider Babylon GP at Hand, headquartered in Hammersmith with five London clinics, had more than 50,000 patients across the country by May 2019. It has now been asked to disaggregate its patient list. Meanwhile, a third of London’s primary care estate is dilapidated and needs replacing at an estimated £8 billion cost. Connectivity between NHS organisations to transfer patient information is considered poor, lagging public expectations.

Budgets and Workforce

Policy specialists calculate that vastly more money than the 2018 NHS funding settlement, which delivers an annual 3.4 per cent spending increase, will be needed to meet the NHS Long Term Plan’s objectives: the Health Foundation calculates £4 billion extra by 2023/4. Social care and public health will need even more.

An even greater challenge, many experts agree, is the NHS workforce. There’s a shortage across England of more than 100,000 staff in the trusts alone – about one in 11 posts – which could grow to more than 350,000 by 2030 in a worst case scenario. London had the worst retention rates of any region in England in 2017-18 with almost 20 per cent of staff in the North Central and East London sub-regions leaving during the year. London nurse vacancies decreased year on year in 2019, but its rate is still the highest in England at 13.5 per cent, with almost one in five mental health nursing posts empty.

The Nuffield Trust found North West London has the lowest number of GPs per head of any English region. A 2018 joint Nuffield Trust, Health Foundation and King’s Fund report argued that the shortfall of GPs would never be made up by simply training more of them, and that pharmacists, psychiatrists, nurses and mental health staff would need to take on some GP tasks in future. Initiatives such that by East London Health & Care Partnership to recruit and retain GPs may help bolster family doctor numbers at a local level.

Brexit adds uncertainty to the mix. 11 per cent of NHS staff in London are EU nationals. Existing employees can apply to remain beyond the transition period under the EU settlement scheme, but will future potential NHS recruits be stemmed or discouraged by the £25,600 migrant salary threshold? Efforts to increase the domestic NHS workforce will take time to work through to extra frontline staff. Meanwhile, there’s concern that after transition, London will pull in NHS workers from other regions because of the earning differential in the capital.

Public Health, the Boroughs and the Mayor

In 2012, responsibility for most areas of public health was passed from the NHS to local authorities, overseen from 2013 by a new body called Public Health England. At the same time, councils’ government grants for spending on public health were radically cut back.

Health inequalities in London have long given grounds for concern. In 2014, Professor Martin McKee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine described large disparities between boroughs in life expectancy rates and incidence of certain terminal illnesses as a scandal. A 2019 Centre for London report found almost double the rate of common mental health disorders among residents of Newham compared with those of Richmond, and the proportion of overweight or obese 10 to 11-year-olds almost double in Barking compared with Richmond. Asked in January by On London about underlying pressures on hospitals, Labour London Assembly health lead and practising GP Onkar Sahota pointed straight away to public health: “A shift should have been taking place on prevention. But the brunt of cuts have been on the public health budget. We’ve always been playing catch-up with health.”

Under NHS England’s London Vision, the Mayor, cross-party body London Councils and Public Health England are partners in furthering ten pan-London public health objectives, plus collaborative work at different geographical scales to make London “the world’s healthiest global city”. A 2017 health and care devolution deal for London established some areas as city-wide responsibilities – for example, incentivising the NHS in London to sell off unused land for housebuilding, generating revenue for investment in care facilities. But it didn’t include public health powers for London to decide how the sugar tax would be spent, or to tackle obesity on a citywide basis.

Sadiq Khan is largely in the same “extremely frustrating” position as the one Boris Johnson told London Assembly Members he was in five years ago. It’s a quite different situation from Greater Manchester, where health funding and decision-making powers were drawn down from central government and up from councils to the combined authority led by that city-region’s Mayor.

Ways Forward?

Conservative London Assembly member Andrew Boff thinks STPs are only about controlling costs and that integrating the NHS into existing democratic structures would enable it to work more effectively. He argues that local councillors should have a role over CCGs and that the GLA should play a part in running hospitals, though former King’s Fund CEO Professor Sir Chris Ham would consider this a lost battle, as he has insisted “there is no Plan B” with STPs.

Labour figures set store by Sadiq Khan’s six tests for NHS reorganisation – including public engagement, clinical support and avoiding bed closures – set out in 2017 in relation to STPs but also applicable to any future proposed reforms. Former shadow health minister Baroness Thornton hopes for a levelling up in standards to embrace best practice within the new larger CCG areas. And Camden councillor Alison Kelly, chair of the North Central London Joint Health Overview and Scrutiny Committee and former head of governance at the Audit Commission, says that, given a long-running commitment to centres of excellence, a crucial part of NHS reorganisation is to ensure free patient transport is available wherever needed, so that all patients have proper access to the best treatment across London.

Impacts of the Virus

The extraordinary efforts to tackle the coronavirus after the UK’s switch to a lockdown approach has forced people and services to come together and driven innovation more quickly than NHS reforms managed. Getting all GPs to offer telephone consultations is one clear example. At the same time, there are concerns among London NHS staff that the building of the Nightingale has seen staff diverted from other hospitals where they are needed more.

Whichever point in recent history it is viewed from, England has a fairly centralised health system by developed world standards. On top of huge national funding and staffing pressures, London has a set of distinctive challenges, which collaborative working and some limited devolution may help resolve – but it’s a long road. Even if, as experts predict, we return to planned programmes of change after the crisis, it will be intriguing to see what Londoners think about and what they will expect of their health service and care systems when it’s over.

Thanks to the King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust for their help with compiling this article.

OnLondon.co.uk is doing all it can to keep providing the best possible coverage of London during the coronavirus crisis. It now depends more than ever on donations from readers. Individual sums or regular monthly contributions are very welcome indeed. Click here to donate via Donorbox or contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com. Thank you.