The Conservative candidate for London Mayor, Susan Hall, is a prolific user of social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, and some of her past activity, such as encouraging Donald Trump to “wipe the smile” off Sadiq Khan’s face by being re-elected US President, have attracted much attention since her selection.

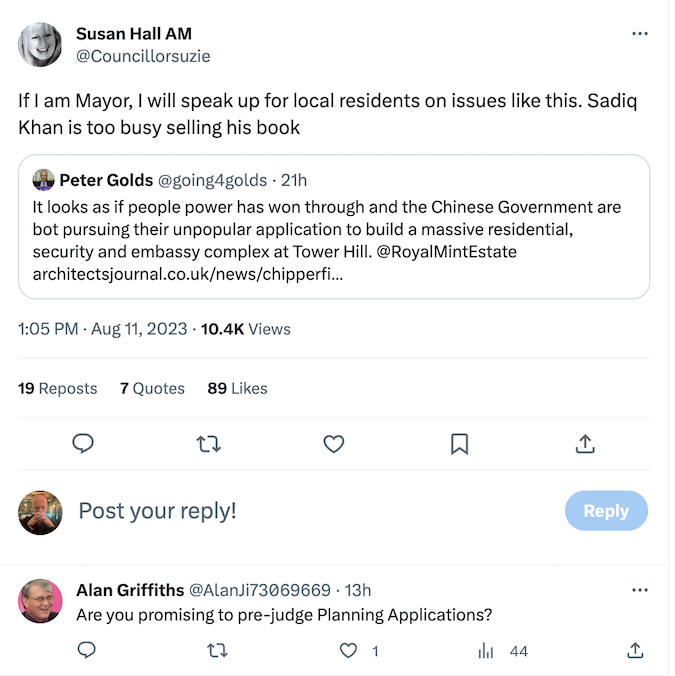

Last week, Hall continued her attacks on Khan in the form of a vow to “speak up for local residents” who object to property development plans proposed in their neighbourhoods. Should Hall be elected Mayor next May, how could this promise be honoured?

A possible difficulty was raised on X by Alan Griffiths, an experienced Labour councillor in Newham. “Are you promising to pre-judge planning applications?” he asked Hall. His challenge went to the heart of London Mayors’ freedom to “speak up” about planning applications and the constraints placed upon it.

Hall’s X remark was made in response to another experienced borough councillor, Conservative Peter Golds of Tower Hamlets, welcoming the Architects’ Journal reporting that the Chinese government appears to have abandoned its long-gestating plan to build a large embassy complex on the Royal Mint site adjacent to the Tower of London and Tower Bridge.

The application was rejected by Tower Hamlets Council in December 2022, and in February Mayor Khan decided not to stand in the way of the borough’s decision, as he could have done given the size of the proposed scheme and its potential importance to London as a whole.

Khan’s role in determining the outcome of the embassy application is an example how the planning policy powers of London’s Mayors relate to those of London’s 33 local authorities – the 32 boroughs and the City of London – and the two mayoral development corporations. Those powers, originally set out in the Greater London Authority Act (1999), have been since been strengthened and are currently defined by a legal order that came into effect in April 2008.

London’s local authorities are required to send to the Mayor copies of any planning application submitted to them that meets the definition of being of “potential strategic importance” to London, for example if it proposes the building of more than 150 dwellings, or exceeds certain heights or amounts of floorspace.

The Mayor or, usually in practice, his or her deputy for planning and GLA planning officers, then have six weeks to decide if the application complies with the policies of the London Plan, the Mayor’s master blueprint for the use of the capital’s land. This consultation obligation, known as Stage 1, entails the GLA providing the local authority with written comments about the application.

Such comments are important, because if the application is found to be in breach of London Plan policies, the applicant will need to alter its plans accordingly. Even if the local authority approves them, they must again be put before the Mayor in a Stage 2 referral to secure his or her final blessing. And a Mayor who withholds that blessing can intervene in one of two ways: either by telling the local authority it must now turn down the application (to “direct refusal”), or by taking over the application so that the GLA becomes the local planning authority instead.

There are rules about how all the decision-makers involved, including the Mayor, must conduct themselves. The GLA’s Unified Planning Code of Conduct includes a general requirement that “any discussion about a specific planning proposal, or planning matters generally, does not prejudge or prejudice the formal exercise or any planning function” (paragraph 7) and “must not do anything by which it could reasonably be regarded as them having a ‘closed mind’ as to the outcome of the decision” (paragraph 17).

That does not prevent a Mayor from expressing views or campaigning about planning matters in general “provided that in doing so they do not do anything from which they could reasonably be regarded as showing they have a closed mind or have predetermined any future planning decision, application or matter, and they must be careful not to give any such impression” (paragraph 19).

Simply put, if an application to a borough is “referable” as defined in the April 2008 order, Mayors must keep their mouths shut about it and their opinions to themselves. Even Boris Johnson, notorious for his disregard for rules, adhered to this stricture when he was Mayor. At Mayor’s Question Time in December 2011, when asked about reports that Chelsea Football Club might seek to build a new stadium on the site of Battersea Power Station, he told a Conservative London Assembly member: “Come on. You would not expect me to fetter my discretion in any planning matter about one proposal or another”.

What happens if a Mayor “speaks up” about an application and breaks the code? He or she might attract a formal complaint, which could lead to censure by the GLA’s monitoring officer. In the meantime, that Mayor might be advised and think it wise to delegate the Stage 2 decision to the Deputy Mayor with responsibility for planning.

In practice, many such decisions are delegated anyway – in the current City Hall administration Jules Pipe often takes them on Mayor Khan’s behalf. Under Johnson, Edward Lister and, before him, Simon Milton, performed such responsibilities. And, given that Mayors’ deputies are very likely to take the same views about planning matters as their bosses and are governed by the same London Plan policies, such delegation is unlikely to make a difference to Stage 2 outcomes.

However, a Mayor who opens him or herself up to being accused of prejudging a referable application – of having a “closed mind” about it – might nonetheless find him or herself in a spot of bother if they block an application a borough has consented, or reject it having taken it over. A developer so thwarted by the Mayor can still appeal to the communities (or “levelling up”) secretary to overturn that Mayor’s decision. Making the case that the Mayor had, to adapted Johnson’s term, fettered his or her discretion by speaking out against their plans while they were under consideration could carry some weight.

Susan Hall has been a member of Harrow Council since 2006, including briefly as its leader, and a London Assembly member since 2017. It seems unlikely that she doesn’t know about the constraints on what politicians can say about planning applications they are charged with determining, including those relating to London Mayors pre-judging referable applications – or, for that matter, that on becoming Mayor Hall she would inherit Khan’s London Plan and be unable to replace it with her own for at least three years.

Perhaps her reaction to Peter Golds welcoming the apparent demise of the Chinese Embassy scheme should be understood as a general statement of localist – or, more pejoratively, Nimbyist – planning policy principles, rather as a signal that she either doesn’t know or doesn’t care what a London Mayor’s responsibilities in this area are. But whichever is the case, Londoners should recognise that whatever Hall might say in advance of the election, she would do well to think very carefully before opting to “speak up for local residents” about major planning schemes should she end up becoming Mayor.

X/Twitter: On London and Dave Hill. If you value On London and its writers, become a supporter or a paid subscriber to publisher and editor Dave’s Substack for just £5 a month or £50 a year.