Last summer, On London began a series of articles tracking the progress of plans to redevelop four blocks of privately-rented flats and another that houses Westminster Council tenants in order to create a new piece of south Belgravia to be called Cundy Street Quarter.

The developer, Grosvenor Britain & Ireland, foresees an attractive mixed-use scheme with better streets and amenities and homes for market sale and “senior living” along with two types of “affordable” housing, half of it for intermediate rent and half for social rent, including dwellings in which current council tenants can be rehoused.

Grosvenor wants its approach to this project to be seen as exemplifying its desire to improve public trust in developers and increase enthusiasm for regenerations that promise more and better housing and neighbourhoods. But their plans have attracted energetic and well-publicised opposition from some of the council tenants and others from the private blocks, with backing from the local Labour Party.

The distractions of the general election and the festive season have meant no On London coverage of this highly instructive case study since October. What has been happening since then?

Quite a lot. A third round of consultations with residents of the existing housing and other local residents was held in the first week of December, seeking views on detailed design plans. A further drop-in day for people to look at and discuss Grosvenor’s proposals took place last week.

Prior to all that, on 4 November last year, a meeting took place between representatives of Grosvenor and some of the campaigners against the scheme who live in the social rented homes in a block called Walden House, which is leased by Westminster Council from Grosvenor.

One of the leaders of the opposition campaign, Walden House tenant and Labour activist Liza Begum, described the meeting, which was attended by the then Grosvenor chief executive Craig McWilliam, as “informative”, though she complained that she “could not get confirmation about where we would live if demolition goes ahead”. However, she added that a dialogue had begun.

Much more recently, on Tuesday, Begum described on Twitter a meeting she had had with an officer at Westminster, complaining that she had received “no concrete answers” about the rehousing of Walden House tenants and claiming that Grosvenor and the council “keep misinforming us and constantly pushing the responsibility onto each other”. The backdrop here is that it’s yet to be decided who the landlord of the replacement social rented homes will be. However, the council, has committed to giving Walden House tenants a “right to return”.

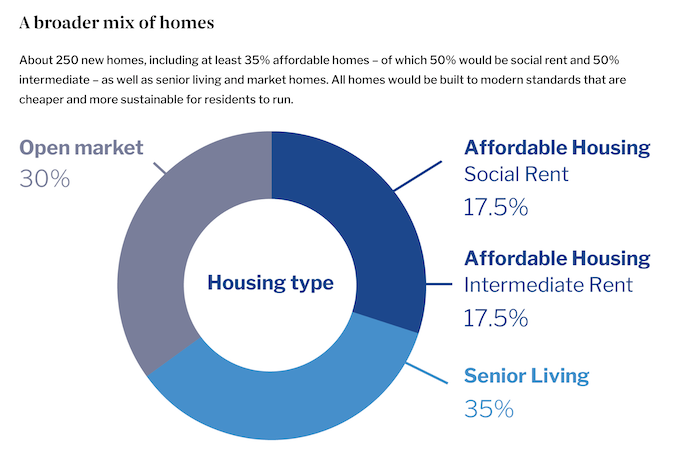

What we do know is that the number of new homes planned for Cundy Street Quarter is approximately 250 – compared with 151 altogether on the site at present – and that 30 per cent of these would be for open market sale, 35 per cent would be senior living homes (for older people), 17.5 per cent would be for “intermediate rent” and 17.5 per cent for social rent. See text and diagram from the Cundy Street Quarter site below.

There will be opportunities later this month for Walden House residents to take a closer look at the designs for the replacement homes they might be offered. Meanwhile, Grosvenor has been working on setting up a community forum for sharing ideas about Cundy Street Quarter, both before and after a planning application is eventually submitted to the council. They have also been talking to the Young Westminster Foundation, a partnership-building charity, about what younger people might want from the development.

Like so many regeneration projects, especially those that entail the destruction of peoples’ homes, the Cundy Street Quarter vision is not being warmly embraced by all those who would be most directly affected by it. At the same time, others, perhaps including some of those who will need to be rehoused, might be seeing it as means by which their lives and neighbourhood can be improved. Having picked up the threads of this particular story, On London will be following them up in the coming weeks.

OnLondon.co.uk is committed to providing fair and thorough coverage of the capital’s politics, development and culture. The site is small but influential and it depends on donations from readers. Individual sums or regular monthly contributions are very welcome indeed. Click here to donate via PayPal or contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com. Thank you.

The issue, as it is in much of central London, is that perfectly decent buildings will be demolished to make profits for developers.

There are plenty of other options available to Grosvenor, including refurbishing the existing buildings, increasing their height, and building new flats on the rather large amount of space on the site currently given over to car parking.

Roping in community groups to give idealites of what they’d like is a fig leaf, covering the developers until the time they reveal that those numbers are unsustainable financially, and that they need to increase the for sale, decrease the rental, and absolutely minimise the social housing provision. We’ve seen it time and time again in Westminster, so where’s the guarantee that it won’t happen again…

On top of that, the climate change impacts of demolition are huge, as will be the local environmental impact from such a huge project (recent experiences from the barracks are a good markets), with endless amounts of demolition and construction traffic; all to satisfy some plan that we all know in our hearts of hearts will not ultimately deliver benefits for local people.