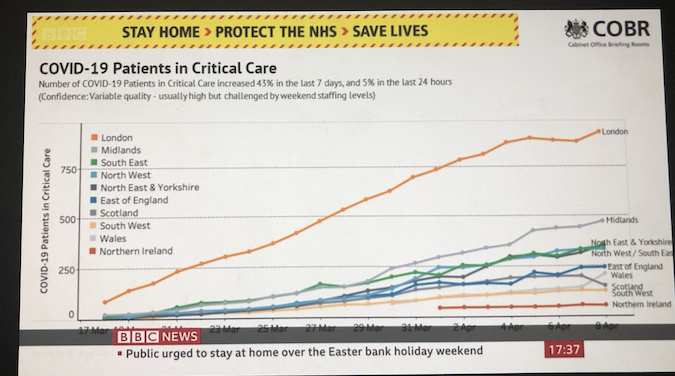

For many, it is already too late. The new coronavirus has been a factor in the deaths of well over 2,000 people in London so far. That figure looks set to grow fast, with close to a further 1,000 currently in critical care (see screen-grabbed Cabinet Office figures shown below). And while most of the 15,217 cases confirmed across the capital altogether since infections were first identified here in February – a rate of 1.7 Londoners per thousand – have not been that serious, they are only the ones discovered by testing, so the real number is thought likely to be significantly higher.

To start grasping the wider implications of those figures for London, it’s worth pondering them in a wider context. A City Hall study published in November anticipates an average of 58,700 deaths a year from all causes in Greater London during the next two decades – just under 5,000 a month.

Any comparison is far from exact: a number of the 2,000 who’ve died with the coronavirus in their systems would probably have died anyway, given that older people and those with underlying health problems account for a majority of fatalities; also, not all “usual” deaths occur in hospitals.

Even so, it is easy to see how 2,000 virus-related deaths in London the space of a few weeks, around half of them in the past week alone, and many hundreds in intensive care every day, has placed the city’s hospitals and other NHS bodies under a large and sudden additional strain. The rapid provision of space for 4,000 beds in the NHS Nightingale hospital in the ExCel centre is a further measure of that.

What does the response to the virus of the NHS in London so far indicate about its fitness for the longer-term future? The question doesn’t relate only to pandemics. Greater London’s population is expected to rise from its present nine million to 10.4 million over the next 20 years. Displays of public support for NHS workers have been powerful and well-deserved. That doesn’t mean the virus has not already exposed weaknesses in the NHS in London or shone a light on ways it will need to change. Covid-19 is serving as an exacting and sometimes lethal stress test. Its results will need to be squarely faced.

The “new abnormal” that all Londoners are having to contend with will reveal much else about London’s governance and may give grounds for bold new thinking. The bruising impact on Transport for London’s already troubled finances has already prompted Centre For London’s Richard Brown to look at different ways in which the capital’s transport systems might be funded. London council leaders of different political parties, from Richmond to Enfield to Greenwich, have expressed despair over the failures of national government to deliver the personal protective equipment their own staff and others in their boroughs need, and found that partnerships with local third sector bodies have been far better than Whitehall in ensuring that basic food supplies reach those who could run short.

A common theme in both these areas is devolution – giving London’s public bodies more autonomy form national government. Local government and the third sector might also be seeing a blossoming of new and established collaborations alike, with a potential for closer and more productive mechanisms for assisting the socially marginal and isolated being discovered.

Meanwhile, the vastly different tasks London’s police officers are suddenly being asked to perform might generate its own set of insights into the Met’s efficiency and aptitudes. And the debate about whether London’s parks should be kept open – as almost all of them are – has focussed attention on the importance of green space for recreation for those many Londoners in who live in flats and too often in overcrowded conditions.

Many of us have already been sharply reminded of the value of our high streets with so many of their outlets now shut down. The damage to London’s economy as a whole, so vital to the rest of the UK too, could be enormous, especially as it substantially depends on leisure, cultural institutions and visitors – sectors that seem sure to be hit hard.

The Mayor said on Wednesday that the peak infection rate in London was “probably a week and a half away”, according to the experts who brief him. That does not mean a smooth and easy return to business as usual will begin next weekend for London’s health services or anything else. The capital’s history has been shaped by past needs to struggle through and recover from calamitous episodes, from plagues and fires to the Blitz, but re-adjustments have taken years if not decades, and have often brought about new forms of social conduct and regulation.

There is a sense, then, in which the coronavirus outbreak is just London’s latest “new abnormal”. But the full ramifications of the pandemic for the city will be huge. They are only starting to become discernible and they are going to be with us for a long time.

OnLondon.co.uk is committed to providing the best possible coverage of London’s politics, development, social issues and culture. It depends on donations from readers. Individual sums or regular monthly contributions are very welcome indeed. Click here to donate via PayPal or contact davehillonlondon@gmail.com. Thank you.