Sadiq Khan’s intervention in the very large and very stalled Earls Court redevelopment project last week – first reported by On London, I’m pleased to say – was welcomed by campaigners against the demolition of two housing estates earmarked for demolition and by Labour-run Hammersmith & Fulham Council (H&F), which has promised a better deal for the estates’ residents since 2014 when it took control of the borough from the Conservatives who had nurtured and approved the scheme. But what, exactly, does Khan’s intervention mean?

His statement, echoing the careful language employed by City Hall officers in private correspondence with interested parties, came as Capital & Counties (Capco), the project’s principal developer, seeks to sell its interest in the main part of the 77-acre site to someone else. Khan said he wants the two housing estates, West Kensington and Gibbs Green, currently subject to a legal agreement to transfer them to Capco, “handed back entirely” to the council before any new plans for the scheme are formally proposed and any such plans to include a far higher amount of new social and other “genuinely affordable” housing than the original ones contained.

But what about those original plans? Outline planning consents for the main part of the site were granted in 2012 and finalised in 2013. Detailed applications for the section of it where the Earls Court exhibition centre buildings then stood – they’ve since been demolished – were granted in April 2014, just before Labour won control of H&F. These planning consents are still in force and will not disappear if and when Capco sells out to another company. Councils can revoke planning consents, but it very rarely happens. They have to be approved by the secretary of state for housing, communities and local government and this happened only three times in the whole of England and Wales between 2009 and 2016, according to a recent House of commons briefing paper. London Mayors can’t revoke them at all.

So what is to stop any new developer simply pushing ahead with the existing plans, whether Sadiq Khan likes them or not? John Moss, a Conservative councillor in Waltham Forest, who, as a regeneration consultant, helped the then Tory H&F formulate the scheme, framed the question well on Twitter: “Sadiq Khan can only secure changes if a new planning application is made. Is that going to happen?”

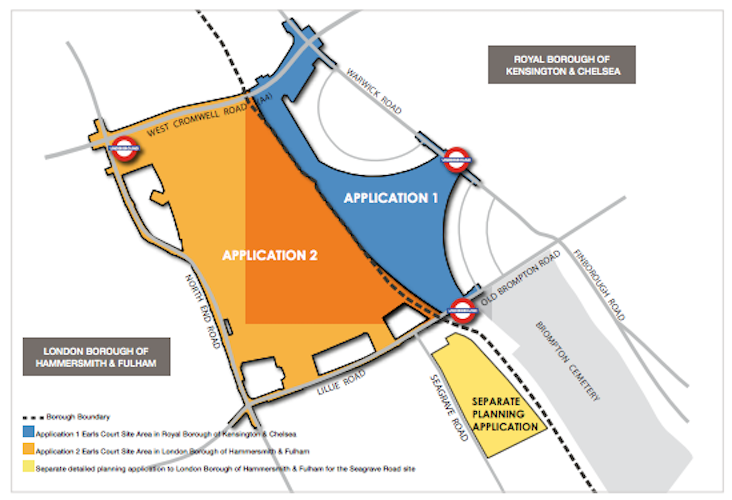

The short answer is that, as things stand, it looks that way. Capco has suggested variations to the plans since Khan became Mayor and the view from City Hall is that new owners would want to start afresh. That might be because they’d have their own vision for the area, but also because they would see the advantage of having a good working relationship with H&F, with Royal Kensington & Chelsea (RBKC) next door – which the eastern end of the site falls into – and with Mayor Khan.

His backing and co-operation would be very welcome, not least because Transport for London, whose board he chairs, would be the principal landowner of the site. TfL is the junior partner in a joint venture company formed with Capco to redevelop the exhibition centre land and it retains the freehold. It also owns the third of the three big sections of the main site, the Lillie Bridge London Underground maintenance depot, for which there is no detailed consent. A tangle of Tube and other rail lines runs through the TfL land.

Far better to have the Mayor enthusiastically backing your brand new plans for the area than disapproving of your attempt to realise some old ones he’d never liked. Far better too to have H&F on board and also RBKC, with its post-Grenfell administration vowing to increase its social housing stock. The Mayor has made it clear that tearing up the deal for knocking down West Kensington and Gibbs Green would be a good place for any new owner to start.

Just to note that councils’ power to revoke previous planning consents is very limited. Unless the consent was obtained in some way fraudulently, it needs the Secretary of State to authorise revocation – and that last happened in 2009.

Just three revocations in the whole of England and Wales between 2009 and 2016, according to a House of Commons briefing paper.

The LBHF freehold only has outline planing consent and detailed consent can be withheld. There is a break clause in the Conditional Land Sale Agreement which means LBHF will get its land back if it blocks development for long enough. LBHF and the Mayor need detailed legal advice on the break clause, which they have failed to obtain.