An inner London without children? That was the stark warning set out at Centre for London’s recent London Conference. Katherine Hill, strategic project manager at child poverty charity 4in10, warned that increasing costs of living in the capital were making the centre of London into a “child-free” area. Munira Wilson, MP for Twickenham, spoke of schools under threat of closure in inner London due to falling attendance figures.

Recently released Census figures from early 2021 show that these concerns are not unwarranted. Although central London is by no means “child-free”, households with at least one dependent child – defined as aged under 16 or up to 18 and in full-time education – are becoming increasingly rare and the contrast with outer London is becoming increasingly marked.

This is shown by the changes apparent from the previous two ten-yearly Censuses. In 2001, Westminster and the City of London stood out for having the lowest proportion of households with children – only 13 and 10 per cent respectively.

This is unsurprising, given the concentration of highly-paid professionals living in private rented accommodation that has persisted in both boroughs, and the relatively small proportion of family homes in their housing stock.

But other inner London boroughs, such as Tower Hamlets and Southwark, still had comparable figures to outer London boroughs in 2001. In both Tower Hamlets and Enfield, for example, 30 per cent of households had dependent children.

By 2011 the differences between inner and outer London began to become more apparent. In Outer London, Harrow went from 30 per cent in 2001 to 36 per cent in 2011. But in inner London Camden dropped from 32 per cent to 22 per cent. By last year, 2021, the comparison was even starker.

The map below show the full picture of changes between 2001 and 2021. We see a sharp reduction in households with dependent children in central London and significant shifts in the other direction in outer London.

There are particular stories within this trend. Barking & Dagenham, for example, saw a 34 per cent increase over the period, spurred by low land prices and an enormous programme of housebuilding that has seen the borough’s population grow by almost 20 per cent over the 2010s, the second largest increase in London.

These numbers show a big change. But there may be more to the picture. They don’t take into account what analysts call “suppressed household formation” when adults are prevented from forming new households, in this case by having children, and so continue living with their parents or in flatshares with friends.

As a Greater London Authority analyst has noticed, during the 2010s London saw by far the largest increase in households with non-dependent – or grown up – children in the country, defined as children aged over 16, or over 19 if still in full-time education. This reflects the growth in young people unable to leave their family home due to high housing costs.

And the percentage of households with children is also affected by overall population levels. In an imaginary borough where no one with children left but lots more childless people moved in, the proportion of households with children would fall without any families being displaced. In reality, of course, we have to take into account the families with young children that would have been formed if conditions had been different.

Why, then, has it become so hard to raise a child in inner London? Although part of this phenomenon can be explained by parents choosing voluntarily to move to the suburbs and exurbs in search of larger houses with gardens, cost pressures seem key.

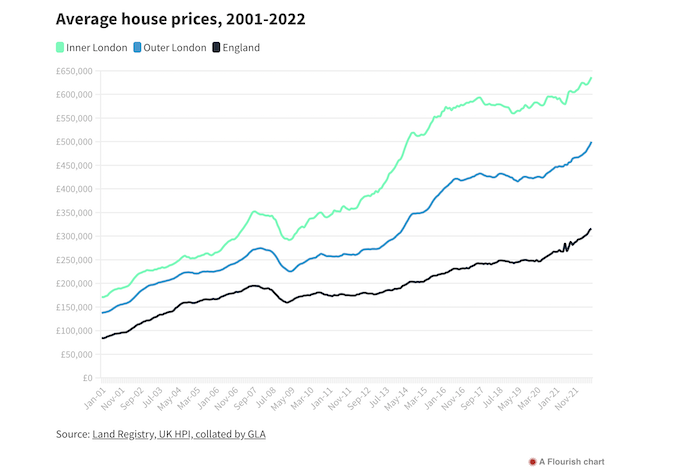

Childcare in inner London is more expensive than anywhere else in the country – nearly a fifth higher than in outer London. Housing, however, is likely most important. The graph below shows the staggering divergence that has formed between average house prices in inner London, outer London, and the English average, pricing many young families out of the centre of the city.

If we want to reverse this trend and make inner London a place where less affluent young families can live again, we will have to tackle our housing problem.

This would require:

- Ending ‘”Right to Buy” in England. Over 300,000 council homes have been sold in London under Right to Buy, many of which are now rented out at extortionate rates on the private rental market.

- A very large increase in the building of social housing in the inner city, which will require a step-change in funding from central government.

- An expansion in private homebuilding, made possible by rationalising the planning system to reduce uncertainty and promote the building of new, low-carbon homes, particularly surrounding public transport.

These are big asks. But if we don’t change things, a child-free inner London may be our future.

Jon Tabbush is senior researcher at think tank Centre for London. This article is a slightly adapted version of Jon’s original, which can be found on Centre for London’s website. Follow Jon on Twitter.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for just £5 a month. You will even get things for your money, including invitations to events such as the one reported above. Details here.