To misquote Hunter S Thompson, “Levelling up is hard to know because of all the hired bullshit”. Is “levelling up” about the north-side divide, about regional infrastructure, about social inequality or about “London-centrism”? The concept is so slippery that there is plenty of space to pick your own perspective. So it’s a relief when the august Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) sheds some light on how money is being spent around the country.

Its report on public spending, published this week, looks at allocations for health services, police, local government, public health and schools across England – in total, around £245 billion in 2022/23. This is where the real money is. Spending on these services dwarves, for example, the £3 billion of Levelling Up Funds provided to England in the first two rounds.

The report breaks down spending by 150 local authority areas (with an interactive map), analysing expenditure per head but also as measured against need. At first glance, the capital’s boroughs fare relatively well, with six in inner London – Camden, Hackney, Islington, Kensington & Chelsea, Southwark and Westminster – among the ten highest-funded areas, each receiving more than £5,000 per head alongside Blackpool, Knowsley, Liverpool and Middlesbrough.

There are, of course, good reasons why spending in London is higher. For a start, wages, which make up around 45 per cent of NHS spending, 50 per cent of local government spending and around 75 per cent of police spending, reflect the city’s higher living costs. London weightings added to wages (seven per cent for police, 2-20 per cent for NHS workers, and 3-18 per cent for council staff) are set accordingly. So, you would expect higher costs in London for equivalent staffing and service levels elsewhere.

There’s a bigger issue too: the figures are based on 2021 population estimates. We know that London saw a sharp fall in population during the pandemic, and this was particularly acute in central London. The IFS shows how different spending per head would be if the calculation used 2020 estimates instead (which would also be more in line with the estimates used to allocate funding). It would fall by an average of £160 per head across London boroughs, and by more than £1,000 per head in Camden and Westminster. Mid-year estimates for 2022, due out next month, will give us some indication of how far London’s population has rebounded.

All that said, it’s no great surprise that urban areas in general spend more: they have higher levels of deprivation and higher levels of need (with a few countervailing areas such bin collections, where rural authorities spend more). This is why central government funding is allocated according to complex formulas intended to reflect need (and the cost of delivering services) as well as population levels. The IFS team has updated these formulas – the government has not done so for ten years – and compared them to spending per head.

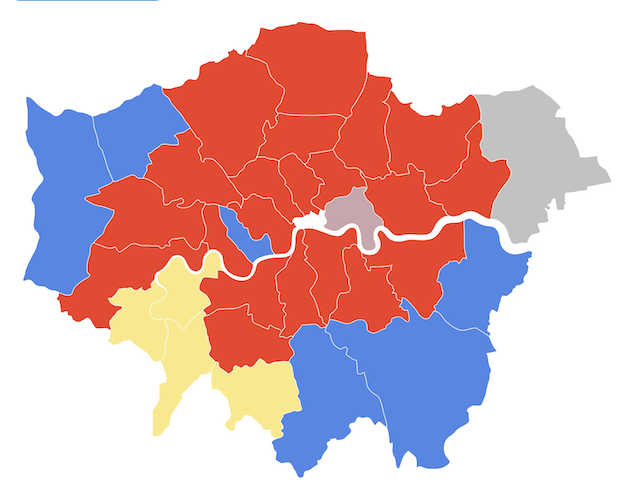

Here the picture is a lot more mixed for London. The capital receives slightly higher funding relative to need for NHS services, though this is largely attributed to the differences between the GP registrations used to allocate NHS funding and the much lower 2021 ONS population estimates. Funding for the police is slightly lower than need, but not as low as it is in other large urban areas. But London’s local government looks very under-funded. Nine out of the ten councils with the biggest relative funding gaps are in London, forming an arc stretching from Barking & Dagenham to Hounslow.

Defunding deprived urban areas is at least partly the result of political choice. As Centre for London and the IFS have explored, cuts in central government funding for councils during the 2010s were applied as fixed percentages, which hit urban areas – with higher need and more dependency on grants rather than Council Tax – particularly hard. As the IFS report observes, needs assessments for local government have not been updated for a decade. But this too is a political choice.

You could conceivably argue that urban areas, which tend to vote Labour, have been over-funded in the past. The Prime Minister hinted at this at an event in Kent (funding eight per cent above relative need) last year when running for the Conservative Party leadership. In fact, the IFS report shows a swathe of well-funded local authorities in the Conservatives’ deep blue Home Counties and midlands heartlands.

Whether this is the result of reasonable policy or low politics is a matter of opinion. But you have to ask if it makes sense in the light of the government’s own proclaimed policy of building in city centres, including London’s. Cutting back public services in city centres, while seeking to grow their populations, does not seem like a sustainable approach to growth, let alone to “levelling up”.

On X: Richard Brown and On London. If you value On London and its writers, become a supporter or a paid subscriber to publisher and editor Dave’s Substack for just £5 a month or £50 a year. A few refinements were made to this article on the morning of 17 August 2023.