Saying that Londoners are underpaid may not win many votes outside the M25, but persistently low pay is a huge problem for the capital and its citizens.

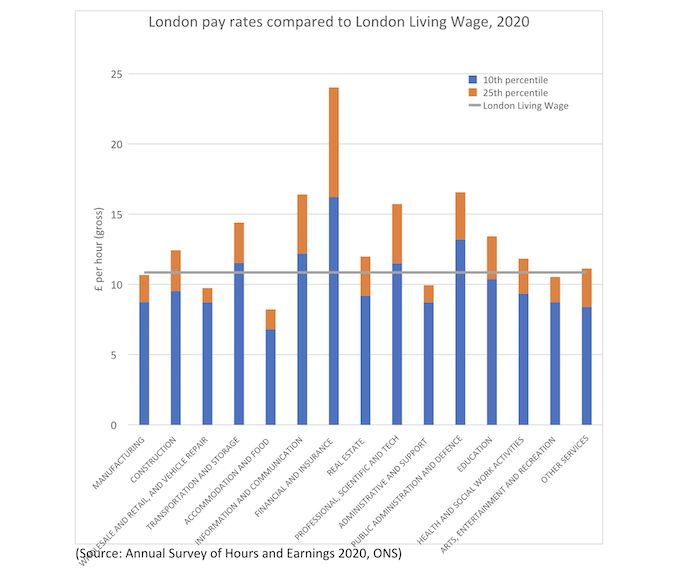

One way of looking at this is to compare Londoners’ salaries to the benchmark set by the London Living Wage (£10.85 in 2020/21), which is calculated as a rate that meets “everyday needs”. The chart below compares this benchmark to London’s 10th and 25th percentile pay rates – that is, the highest pay for the bottom 10 per cent and bottom 25 per cent of earners respectively – for sectors where there are enough workers to enable reliable estimates.

The chart shows where London’s low pay problem is concentrated. Twenty-five per cent of workers in retail, hospitality, admin support (jobs like security guards), social work (bundled with better-paid health jobs above), and entertainment were being paid less than the minimum hourly rate needed to live in London in 2020. Hospitality wages are particularly low: more than 60 per cent of workers in that sector were paid less than the London Living Wage.

There are two other things worth noting. Firstly, low pay may be a national problem, but it is more acute in London. Loughborough University research on “minimum income standards” indicates that Londoners in different household types need between 20 and 60 per cent more than people in other UK urban areas to afford a decent quality of life.

London jobs do pay a wage premium, but this is less than 10 per cent at the bottom end of low-paid sectors such as hospitality, security, residential care work and construction. In other words, the workers who most need the wage premium to live in London are also those least likely to get it.

Second, London’s lowest-paid sectors – industries such as food production (one of the lowest paid manufacturing sub-sectors), hospitality and social care – are some of those with the most acute labour shortages at the moment. (Others shortages, such as of HGV drivers, are complicated by the need for specialist training and licences.) They are also the sectors which have been most dependent on overseas workers in recent years.

The issue of labour shortages is hitting the news – and supermarket shelves – right now, though maybe the problem will solve itself over the coming weeks, as the distorting effects of pandemic support measures are removed. The furlough scheme, which has been accused of keeping workers in defunct jobs, rather than pushing them to look for new ones, ends next month. But it has been winding down for a while – the number of furloughed jobs in London halved between the end of February and end of June (though this is a slower rate of decline than other English regions) – while labour shortages have persisted or worsened as the economy has re-opened.

The other element of pandemic support has been the temporary £20 per week increase in Universal Credit (UC). More than a million Londoners were claiming UC in June 2021, three times the number two years earlier. Some of these are people who are out of work, but nearly 400,000 are working Londoners whose pay is simply not adequate to their needs. The removal of the £20 per week increase in UC, also due to take place at the end of next month, might encourage some non-working Londoners into employment, but will also push more working Londoners into poverty.

If people won’t be forced back into low-paid jobs by the removal of state support, can we look overseas instead? As border restrictions relax, London may once again attract workers from around the world, though the new immigration regime will prevent new arrivals for working in some of the city’s most crisis-hit sectors.

But by debating how we can use imported labour and benefit subsidies to fill jobs that don’t pay enough, maybe we are asking the wrong questions. Beyond the question of basic morality, coronavirus has exposed the precariousness of this approach to staffing our shops, bars, restaurants, building sites and care homes. Low pay may even be holding back innovation, as the Resolution Foundation recently observed, and hence productivity growth.

London’s economy is likely to change dramatically in coming years as the long-term impacts of the pandemic combine with the impact of technology and action on climate change. To be ready for these changes and the opportunities and disruptions they will create, London needs to pay workers better (as proposed by my former colleagues at Centre for London) or find smarter ways of doing their jobs. We can no longer afford low wages.

On London is a small but influential website which strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.