In 1719, a man went to live in the maritime village of Rotherhithe by the Thames to enjoy a well-earned retirement after a career as a shipwright, running his own business in the new colony of America. Although the business was successful for most of its time, in the end it left him poor. But this was no ordinary man. It was Thomas Coram, one of the most extraordinary people in Georgian England.

On his frequent walks around London, Coram was stunned by the number of dead and dying babies, mainly illegitimate, he saw abandoned – can you believe it? – in the streets and on dust heaps. Horrifying statistics indicated that in crowded workhouses babies aged under two years died at a rate of almost 99 per cent. They were described as “Britain’s dying rooms”. One report suggested that in Westminster Parish only one in 500 foundlings survived.

It is a sobering thought that at a time when Britain was inhumanly treating slaves abroad it was also allowing its own unwanted children to die on the streets of its capital. Although he was 54 years old – a good age in those days – Coram decided to do something about it. And he did. Thanks to his untiring efforts and refusal to take “no” for an answer, the Foundling Hospital became what must have been the most successful charity in the country.

The Hospital was eventually built in Bloomsbury at Lamb’s Conduit Field, on the spot now called Coram’s Fields (main picture). This followed unsuccessful efforts to get it located in Montagu House, where the British Museum is today. What is less well known is that Bloomsbury is not where the institution was originally based.

During its first and formative years it was located in Hatton Garden – before it became an international centre for gems – in a dwelling belonging to Sir Fisher Tench, the MP for Southwark. Tench had grown enormously rich on a range of activities including, it has to be said, the slave trade (though the Foundling Hospital was not in any way connected). William Hogarth’s famous painting of Coram was presented to the Hospital while it was based at this temporary home.

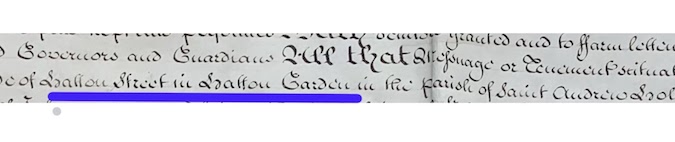

Gillian Wagner says in her biography of Coram that the Hatton hospital consisted of four rooms, with two staircases to the second floor and a yard at the back, though its exact location is still a bit of a puzzle. A document in the London Metropolitan Archives recording the arrangement (see below, underlined) says it was in Hatton Street in Hatton Garden, but Hatton Street does not appear on a contemporary map. Maybe in those days it referred to the street we call Hatton Garden today, while Hatton Garden may have been the name for the area as a whole.

There is also a contemporary reference to it being “next to the charity house in Hatton Garden”, which probably refers to St Andrew’s charity school, supposedly designed by Christopher Wren. The school’s facade can still be seen in Hatton Garden (photo below), though the building behind it has been reconstructed as offices.

Coram’s attempts to raise funds for his project were turned down successively by the government, various institutions and a number of prosperous men. He then had the bright idea of seeking the help of aristocratic women instead, and soon made such a success of it that the men felt obliged to follow.

By 1737, this humble man had signed up dozens of dukes and earls plus the Privy Council and even Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole. Coram won them over by walking around London from house to house to secure their signatures. It was a shining example of the golden years of philanthropy when privileged people, sometimes with ill-earned money, filled the social gap that governments recoiled from.

Sadly, Coram fell out with his fellow governors, but he retained a passion for the hospital – which, in 1935, moved to Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire – until his death in March 1751. It would never have existed without him, and for well over 100 years it was the only institution in London that took care of illegitimate children. Coram’s tomb (pictured below) is at St Andrew’s Church on St Andrew’s Street, just below the southern end of Hatton Garden.

There was at least one unplanned consequence of all this: Hogarth, who was a founding governor of the Hospital, set up an art exhibition at its Bloomsbury home, encouraging other artists, such as Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds to show their works there too.

Visitors flocked to view Britain’s first public art gallery at a time when they were almost unknown in Britain. It is reckoned that exhibitions organised there by the Dilettante Society led to the formation of the Royal Academy in 1768. The pictures can still be seen at the Foundling Museum.

This article is the sixth of 25 to be written by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in Holborn, Farringdon, Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury and St Giles, kindly supported by the Central District Alliance business improvement district, which serves those areas. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.