St James’s Square, just north of Pall Mall, was built by Henry Jermyn, Earl of St Albans and the man credited with inventing the West End of London. In 1661 he had been given a lease by Charles II to build on what had previously been mostly open land. The square was constructed, unashamedly, to attract residents of quality – the nobility and gentry – likely to attend on the king. In the early 18th century, six dukes and seven earls lived there and, over time, 15 Prime Ministers, including three in the same house (not all at the same time). The east, north and west sides of the square contained some of the most desirable homes in London.

In the centre of the square today is a statue of King William III, Protestant hero and, from birth, Prince of Orange. He became king in 1689 after the overthrow of the Catholic James II in the so-called Glorious Revolution. It was unusual but unsurprising that the proposal to erect a statue in William’s honour in the square was made soon after, in 1697: unusual because he was still alive, unsurprising because many of his strongest supporters lived there. The official notice board tells us that it was not finally erected until 1808. Could that be a misprint? Could it possibly have taken 111 years to put up a statue?

The answer is yes. Money, as usual, was part of the problem. William died in 1702 from pneumonia, which he contracted following a hunting accident. His horse apparently tripped over a mole-hill, a mishap depicted by the statue (bottom photo). But a series of attempts to fund a memorial failed. A solution seemed to have been found in 1724 when Samuel Travers MP left a bequest in his will for an equestrian statue “to the glorious memory of my master William the Third” to be built either in St James’s Square or in Cheapside. However, no one was able to agree about the details.

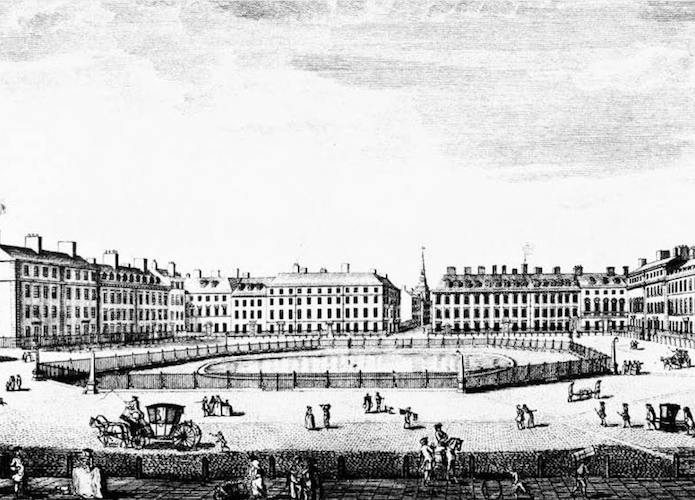

In 1728, an ornamental basin of water 150 feet in diameter was installed in the square, and in 1732 a pedestal followed – but still no statue. In 1739 one was apparently commissioned from Henry Cheere, his brother John Cheere, or maybe both. Made from lead, it depicted William on a horse which, for whatever reason, never managed to gallop to St James’s Square. It may to be the mounted likeness of William that today can be seen in Petersfield. Other statues of William can be found in Kingston-upon-Hull, Glasgow, Bristol, Portsmouth, Ireland (north and south), Amsterdam and in Kensington Palace, the latter an ill-timed present from Kaiser Wilhelm II, who went on to lead Germany against the allies in World War I.

Lamberts history and survey of London claims that during the Gordon Riots of 1780 the mob threw the keys of Newgate Prison into the water in the square, and that they weren’t found until several years later. Not until 1794 was a William statue for St James’s Square at last successfully commissioned. The task was given to distinguished sculptor John Bacon Senior, who inconveniently died before he could fulfil it. However, the statue was eventually completed by Bacon’s son, John Junior, using his father’s design and cast in bronze.

Where the money came from is still a bit of a mystery. The antiquary John Timbs tells us it was not erected until 1808 because “the bequest in 1724 [presumably the Travers donation] for the cost having been forgotten, until the money was found in the list of unclaimed dividends”.

The statue, Grade I listed, still stands serenely among the plane trees (the basin of water is long gone). Bacon Senior was influenced by the equestrian statue of William in Bristol produced by the Flemish sculptor John Rysbrack, who also created Isaac Newton’s monument in Westminster Abbey. As in Rysbrack’s piece, the William in St James’s Square is portrayed as if he were a Roman general holding a baton in his right hand.

No one seems to know why Bacon’s work took so long to build. Perhaps there should be a special category for it in the Guinness Book of Records. It surely won’t mind waiting.

All previous instalments of Vic Keegan’s Lost London can be found here and a book containing many of them can be bought here. Follow Vic on Twitter.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for just £5 a month. You will even get things for your money. Details here.