Reasons for the success of London’s schools have been debate down the years since they changed from being some of the worst in the country at educating children to, by some distance, the best. How much credit should go to the London Challenge programme of the last Labour government? How much to the high proportion of children of migrants from overseas, eager to succeed in the capital of the country their families have taken the huge step of making their own? How much, as has also been argued, to the legacy of Conservative national curriculum reforms in the 1990s?

What is not in question is the capacity of London schools to give children lacking advantages in life most of their peers enjoys the education they need to transcend such handicaps. Last week, the Sutton Trust, a distinguished education charity that conducts research into social mobility, published an Opportunity Index which compared the progress of children in every part of England eligible for free school meals (FSM) at age 16 until they reached 28.

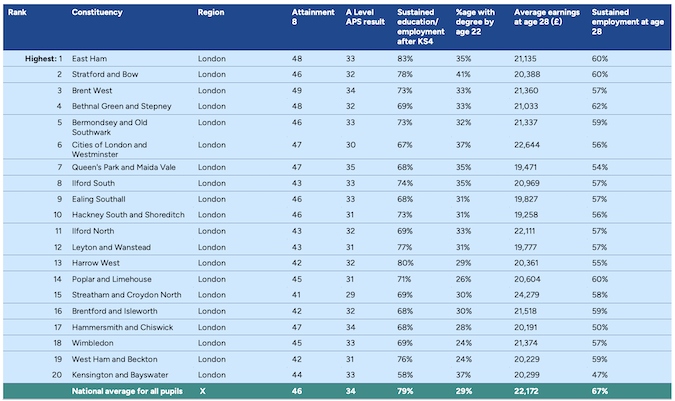

Broken down by parliamentary constituency, the index told a heartening story about secondary schooling in London and a dispiriting one about everywhere else. All top 20 places in the index were London seats, headed by East Ham, Stratford & Bow, Brent West, Bethnal Green & Stepney and Bermondsey & Old Southwark. London’s preeminence was such that it took all but eight of the top 50 places and had none at all in the bottom 200.

Free school meal teens taught in London schools had a 35 per cent chance of having a degree by the time they were 22. The figure for Newcastle was just 10 per cent. Of London’s FSM kids, 18 per cent made it to the top 20 per cent of earners compared with just seven per cent in the North East, and 45 per cent rose to the median range, compared with only 27 in both the North East and in Yorkshire & Humberside.

Areas with high numbers of ethnic minority children do well in the index. London is full of those, of course. Across the country, greater amounts of deprivation makes it harder to lift FSM children up, yet those in London – which has more of them than many think – do well anyway.

It is a glorious story. But there’s another side to it. On that side we find the London FSM kids who don’t transcend hardship and join the higher earners – the 40 per cent who are not in “sustainable employment” 12 years after taking their GCSEs. There are fewer of them than in Newcastle, but still too many. What needs to happen in order for more of them to find secure, solid jobs that provide a decent pay and, with luck, a bit of satisfaction and progression along the way?

The Sutton Trust’s recommendations for all regions include steps to increase the supply of apprenticeships for young people and breaking down barriers that hinder those from the hardest backgrounds getting on. Some such steps are being taken. Last autumn, the government announced reforms to the poorly-working apprenticeship levy, asking employers to “rebalance their funding” to “invest in young workers” following a ten-year decline.

Control over how the re-named “growth and skills” levy works in London is not yet in the hands of City Hall, but there is talk that it will be, along with hopes that it will make a significant and, as yet, unheralded improvement.

Businesses do not seem overjoyed. Already unhappy about increased National Insurance bills, they are now trying to get to grips with how the altered apprenticeship scheme will work.

A survey for BusinessLDN last year found that time and money are the problems most often mentioned by firms struggling with skills shortages of various kinds, though the relevance and whereabouts of local training figured too. Those involved with the London Local Skills Improvement Plan are seeking to adjust to the new situation.

Meanwhile, London government has just been given £30 million of “youth trailblazer” money to spend on five programmes for getting 18-21 year-olds into study, training or working for a year, contributing to the London Growth Plan drawn up by London Councils and the Mayor with its “inclusive talent strategy”.

The capital’s portion of the national adult education budget, covering all age groups, was handed down to London in January 2019. Can that autonomy be built on to give London’s skills training landscape more clarity and relevance at all levels?

If so, maybe employers in key sectors, notably construction and hospitality, which soon won’t be able to recruit so easily from overseas, will start searching closer to home. And maybe those young Londoners who need a bit more than what their schools already give them to shake free of poverty will turn out to be what they’re looking for. And maybe London’s education story will become prouder still.

OnLondon.co.uk provides unique, no-advertising and no-paywall coverage of the capital’s politics, development and culture. Support the website and its writers for just £5 a month or £50 a year and get things that other people won’t. Details HERE. Follow Dave Hill on Bluesky. Photo from London Councils.