The last business of the London borough elections of 2022 was concluded yesterday with a by-election in South Croydon, producing a comfortable Conservative win. The election was needed because Jason Perry, who was elected for the ward on 5 May, had to immediately resign as a councillor because he had also been elected Mayor of Croydon and could not fill both posts.

This seems a good point to look back at some of the electoral currents that flowed beneath the surface of the headline results. It is in the nature of a huge metropolis like London that as soon as one thinks one has found a valid generalisation, evidence appears to confound it. It is also more difficult to measure electoral change than usual this time because the majority of boroughs had ward boundary changes. But let us try to pick out some cross-borough trends from the results.

1. The end of the ‘leafy’ Tory ward?

The Conservatives suffered brutal defeats in many now former strongholds, typified by the losses of largely affluent areas in Westminster and Wandsworth to Labour. Despite Labour’s lonely gain of the Putney parliamentary seat in the 2019 general election, nobody expected the Tories to lose a council seat in East Putney ward, where one of their surviving councillors is now former Wandsworth leader Ravi Govindia.

The Tories were also wiped out in Lambeth for the first time, losing their toehold in the posh bit of Clapham (following Southwark where the last Tory bit of Dulwich succumbed to the red tide in 2018). In Camden they lost a seat in what was supposed to be a much smaller, safer version of Hampstead Town, although they have a chance to recover it because the Labour winner – as surprised and unprepared as everyone else – stood down shortly after being elected. In Ealing, Ealing Broadway ward is now the only one with a full slate of Conservative councillors.

But there were some exceptions where educated professionals still voted Tory: they only lost one councillor in the Chiswick wards of Hounslow, for example, and threats to some wards in Fulham and Kensington did not amount to anything. Chiswick votes Labour in general elections now, so local Tories must be doing something right.

2. Big outer London estates – most of them – swing back left

One of London’s political micro-climates consists of the large outer London estates that were built by the London County Council up to a century ago, initially as part of the “homes fit for heroes” programme after the First World War. Becontree and Dagenham form the biggest of these estates, but there are others scattered around – Harold Hill (Havering), Hainault (Redbridge), St Paul’s Cray (Bromley), New Addington (Croydon), Downham (straddling Lewisham and Bromley), St Helier (Sutton and Merton) and Watling/ Burnt Oak (Barnet).

These estates used to be some of the safest Labour wards in London, surviving the party’s worst ever local election results in 1968, but the Conservatives and sometimes the Lib Dems made serious inroads during the 2000s, and they were some of the strongest areas for the BNP and UKIP.

In 2022 Labour did reasonably well in a lot of the outer London estates, for instance winning all six seats in the Harold Hill wards and representation in the Sutton part of St Helier for the first time since 2002. But these wards did not return to their previous safe status: Hainault swung slightly to the Tories and is now one of their better wards in Redbridge; and New Addington voters seemed particularly unhappy with Croydon’s ousted Labour administration, the Tories breaking through to gain three of the four seats in the area’s two wards.

3. Inner London ex-council estates return to Labour

There is rarely a straightforward relationship between social and demographic trends and political outcomes, at least not over the longer term. Council house sales in inner London under right-to-buy turned grateful ex-tenants into homeowners who had acquired valuable assets in London’s preposterous property market. Buying somewhere in the best-built or best-located estates was like winning the lottery and cemented Conservative dominance. In Westminster in the 1990s the Tories started winning wards based on council-built housing. But turn the clock forward 30 years and these areas have all gone back to Labour, despite Pimlico South ward being within considerably bluer boundaries than its predecessor, Churchill. What has happened?

My theory is that the people who bought the flats originally are still grateful, but have either sold up or use the flats for rental income, and now live in Orpington or Margate or Marbella. The people who now live in the right-to-buy flats are private tenants, paying a fortune to live somewhere a previous generation could easily afford. They are mostly young, educated and diverse professionals of the sort who have turned their backs on the Tories. There are few sharper educations in the generational political economy of Britain. Secondarily, people who live in council-built estates are often easy to contact, in contrast to those in private blocks – tower blocks and deck access flats are easy to door-knock and leaflet and their residents consequently easier to mobilise if a party has the sort of mass membership that London Labour does.

Right-to-buy, therefore, helped create the retired, working-class, property-owning Tory generation that dominates British electoral politics, but in attempting to transform the political character of particular localities through the housing market it planted the seeds of its own subversion.

4. Hindu London swings to the Tories

The Conservatives’ good result in Harrow, winning it back from Labour, had fewer obvious explanations in local politics than their similar success in Croydon. The Labour council was not popular, but councils rarely are. The best Conservative results at ward level in Harrow were in the south eastern corner around Kenton and Centenary, which are the most strongly Hindu parts of London, and this patch of success extended across the border to similar wards in Brent. The Tories held their three Brent seats in Kenton and gained two in Queensbury. In Ealing, the most Asian Southall wards showed swings to the Conservatives as well. There is something going on beyond the immediate politics of Harrow. Despite the strong headwinds of national government unpopularity, a long term trend that may be a major factor in election strategy two or three general elections down the line can be glimpsed.

5. Demography doesn’t seem to be destiny

Over the long term, given that London is constantly in social flux, some of the more surprising political trends are where the electorate has changed radically but the party politics has stayed the same. The inner north London boroughs – Hackney, Islington, most of Camden and the south of Brent – became Labour in the second quarter of the 20th Century when predominantly white working-class communities. Their electorates have since become polarised between educated professionals and the ethnically diverse poor, yet they are as strongly Labour as ever while. Conversely, there are parts of London suburbia where the BAME population has gone up from around seven per cent in 1991 to perhaps 50 per cent in 2021 yet the Conservatives have remained on top with barely a ripple in their vote share – Ruislip and Northwood in the north of Hillingdon are probably the clearest examples.

There is also the curious case of the dog that didn’t bark – the Tory vote in Barking & Dagenham. Dagenham itself was purpose built for social renting to skilled working-class families. The right-to-buy has been popular, the local politics of apparently similar communities in south Essex next door has been transformed, and at parliamentary level Dagenham & Rainham has become perilously marginal – the Conservatives narrowly failed to win it in 2019. Shaun Bailey carried seven wards in the borough in the mayoral election in 2021. But not only did the Conservatives fail to win any wards in 2022 they did not come very close, even in Eastbrook & Rush Green bordering on Romford. Part of the answer must be mobilisation – turnout in the borough was only 24 per cent. But it is probably also that Darren Rodwell’s Labour administration is reasonably popular.

6. General election portents

The swing overall between the 2019 general election and the 2022 local elections was small, although comparing the two is full of pitfalls. Nevertheless, some of the constituency results stand out: Labour led by 13 points in the Boundary Commission’s new version of the Beckenham constituency; Bromley will probably sustain a reasonably reliable Labour parliamentary seat in the future. The Conservatives retained leads in draft constituencies in Westminster and Chelsea, yet the margins were unconvincing and it is possible that in general election conditions the little blue island in the middle of London will vanish entirely. The Liberal Democrats were comfortably ahead in their target seat of Wimbledon, with 38 per cent compared to a very weak 29 per cent for the Conservatives (and 33 per cent for Labour, Greens and Merton Park residents together). The loose proposed successor to Barry Gardiner’s Brent North seat, Kenton & Wembley West, delivered a Labour lead of only nine points, and with the right Tory candidate it could be vulnerable.

7. How low can the Tories go?

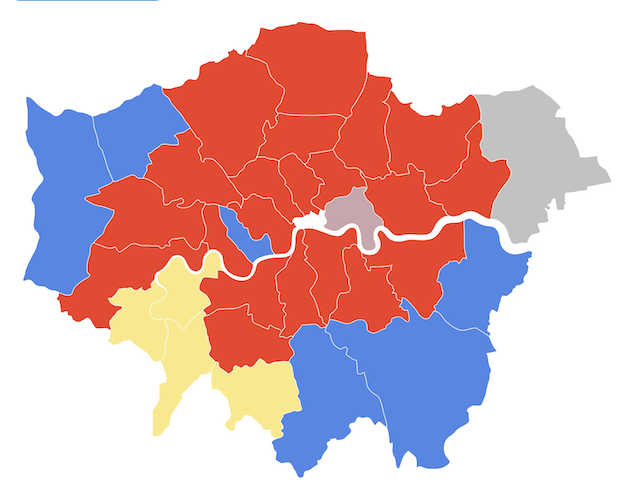

It is quite possible that the 2026 borough elections will see Tory London reduced to just two boroughs, especially if the Conservatives are still in charge of the national government by that time. Only one, Kensington & Chelsea, has been under continuous overall Tory control since the year 2000 and seems likely to remain so. Bexley looks securely held. That is mostly because an unimpressive six-point lead in vote share translated, thanks to the electoral system, into a 33-12 majority over Labour, but only two wards – East Wickham and Crayford, each with three councillors – look particularly vulnerable.

But Hillingdon moved closer to the edge. The Conservatives prevailed 30-23 with a seven-point lead in votes. But while in 2018 it was difficult to see a Labour path to a majority, it is now considerably easier. And Bromley produced one of the more ominous results for the Conservatives, due to a pincer movement of Labour, Lib Dem and Chislehurst residents’ candidate gains. Before 2022 the Tories had been 20 points ahead of Labour even in the latter’s best years, but in May this margin shrank to just eight points and the Tories polled their lowest vote share in the borough’s history – 38 per cent compared with Labour’s 30 per cent, which was their best.

Losing the next general election appears, paradoxically, to be the shortest route to London Tories finding a political formula that works for them in a city which voted strongly for them as relatively recently as 1992.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for £5 a month or £50 a year and receive an action-packed weekly newsletter and free entry to online events. Details here.