Turnmill Street in Clerkenwell is one of the oldest thoroughfares in London. It has seen it all, from high life to low life, from thriving small businesses to abject poverty and, most curiously, being lionised by the likes of William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson. The street has been there, sometimes known by its alter ego Turnbull Street, since medieval maps were invented. Its history and that of its immediate neighbourhood are a microcosm of London’s constant re-invention of itself.

There was a horse and cattle market at next door Smithfield from at least the 12th century, and before the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s the district must have been a paradigm of Merrie England. Situated near the Priory of St John, which dispatched escorted pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and the nunnery of St Mary, it lay outside the bustle of the City of London, and where Turnmill Street ended, so did the capital. Some maps even named what became the adjacent Farringdon Road “Town’s End Lane”.

The Dissolution created a break with the area’s previous history. It threw huge amounts of religious lands on to the market to be snapped up by aristocrats and Henry VIII’s court favourites. William Pinks, the chronicler of Clerkenwell, says that towards the end of the 17th century it was “a delightful place of residence attracting nobility”, yet the 1661 rate book showed 112 people Turnmill Street residents assessed as poor.

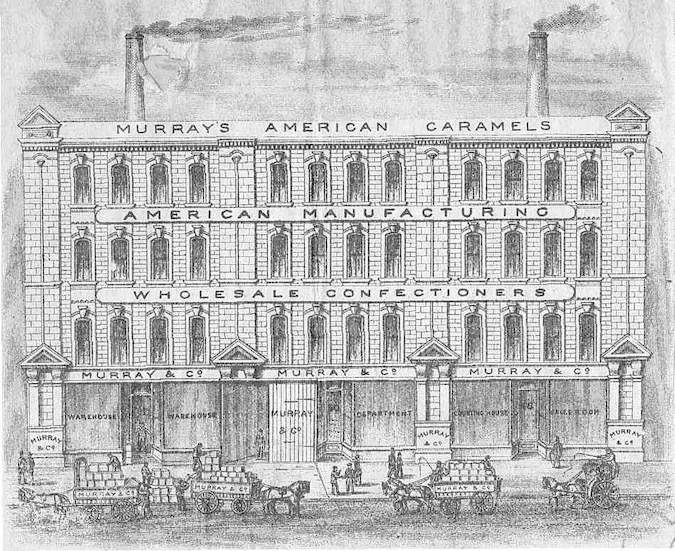

Craft industries arrived, including clock and watch making by Huguenots fleeing persecution in France. Some of these trades were powered by the mill that gave the street its name and also emptied effluent into an already-polluted River Fleet. The industrial revolution brought more immigrants, this time from Italy, and also bigger industries, such as breweries, distilleries and printing. The American caramel manufacturer Murray & Co. (below) employed 300 people in Turnmill Street and the headquarters of Booth’s Gin was based in and around it for 200 hundred years.

The biggest transformation came in 1863 with the arrival of the Metropolitan Railway, the world’ first underground service, which initially ran from Paddington to near the end of Turnmill Street. Butchers, bakers, candle manufacturers, coach builders, craft activities and even charcoal burners in Turnmill Street had to move as buildings on the west side of the street were demolished for the Clerkenwell “improvements”, which also involved building the new Farringdon Road.

One outcome was the decline of the most notorious red light district in the whole of London. Turnmill Street might have been designed for depravity – a short road with least 20 narrow alleys or courts on either side, filled with criminals and prostitutes. What made it different from other London rookeries was the attention bestowed on it by an amazing number of great literary figures.

Shakespeare lets Falstaff (in Henry IV, Part 2) moan that Justice Shallow “hath done nothing but prate to me of the wildness of his youth and the feats he hath done in Turnbull Street”. Pericles was written in conjunction with resident innkeeper and brothel owner George Wilkins, which lends an unusual authenticity to the play’s brothel scenes.

In Ben Johnson’s Bartholomew Fair, Ursula is indignant at being charged with frequenting Turnbull Street. A character in Thomas Middleton’s Chaste Maid has twins by someone she met there. Thomas Webster’s A Cure for Cuckolds features someone who comes to an inn in Turnbull Street and “falls in league with a wench”. In Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher’s play The Scornful Lady a character moans that the “drinking, swearing and whoring” that has been going on means “we have all lived in a perpetual Turnbull Street”. And so it goes on.

Much of the surrounding area became known as “Jack Ketch’s Warren,” because so many people there ended up being hanged, as can be seen in the Old Bailey’s online records. Jack Ketch was the common name for a hangman.

A pub at the junction of Turnmill Street and Cowcross Street, which used to form part of the southern end of Turnmill, has left a particular mark on history.

Imagine the scene. A man had been gaming at the notorious Hockley-in-the-Hole bear baiting pit, which stood on the site of today’s gastropub The Coach (where you can hear the subterranean flow of the Fleet from a drain outside the front door). He ran out of money and asked the landlord of the Castle Inn if he could lend him some money to pay off his debt. As he proffered a gold watch as surety, the landlord was happy to oblige, even though the man was a stranger.

The owner of the timepiece turned out to be George IV on one of his notorious escapades. A few days later, a messenger from the King arrived to redeem the loan with a handsome amount, and, apparently, to grant the landlord a licence to be a pawnbroker.

Whether this story is true or false is for the reader to judge. But what cannot be denied is that a 19th century reconstruction of the pub, called The Castle, which stands on the same spot today, has a handsome pawnbroking sign outside, the only pub in the country to boast one. Inside there is an impressive oil painting depicting George handing over his watch (see main photo). That alone makes the pub worth a visit. Just don’t ask for a loan.

This article is the 20th of 25 being written by Vic Keegan about locations of historical interest in Holborn, Farringdon, Clerkenwell, Bloomsbury and St Giles, kindly supported by the Central District Alliance business improvement district, which serves those areas. On London’s policy on “supported content” can be read here.