Most of analysis of the European Parliament elections held between 23 and 26 May across the EU has naturally focused on their impact on national and international politics. In the UK, this coverage has also been inextricably linked with the Prime Minister’s decision to step down, which has triggered yet another Conservative leadership election.

But now the dust has settled, it is worth considering the implications of the results for the capital. OnLondon has already published a very helpful examination by Lewis Baston of what they mean for each party. We reflect on the party political implications of those elections here too, but also read the tea leaves for insights into the next big polls in London: the May 2020 elections for London Mayor and the London Assembly.

The results

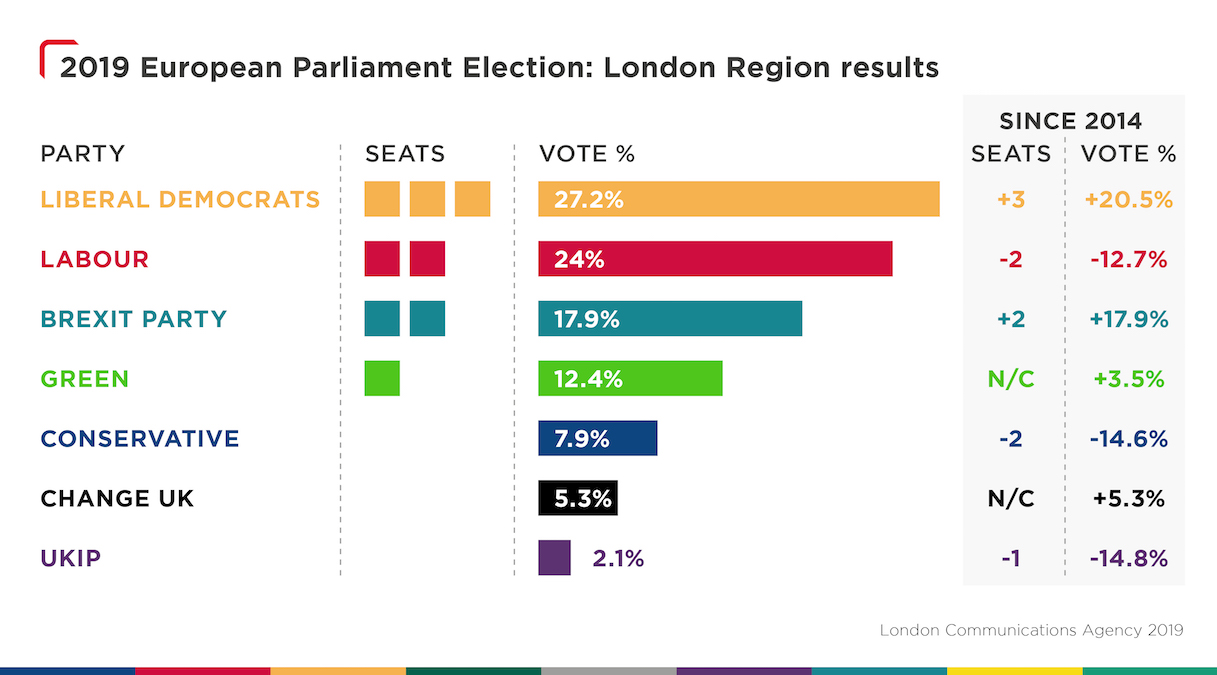

In terms of vote share, the table below compares the results by party between 2014, the last time European Parliament elections were held, and last month’s.

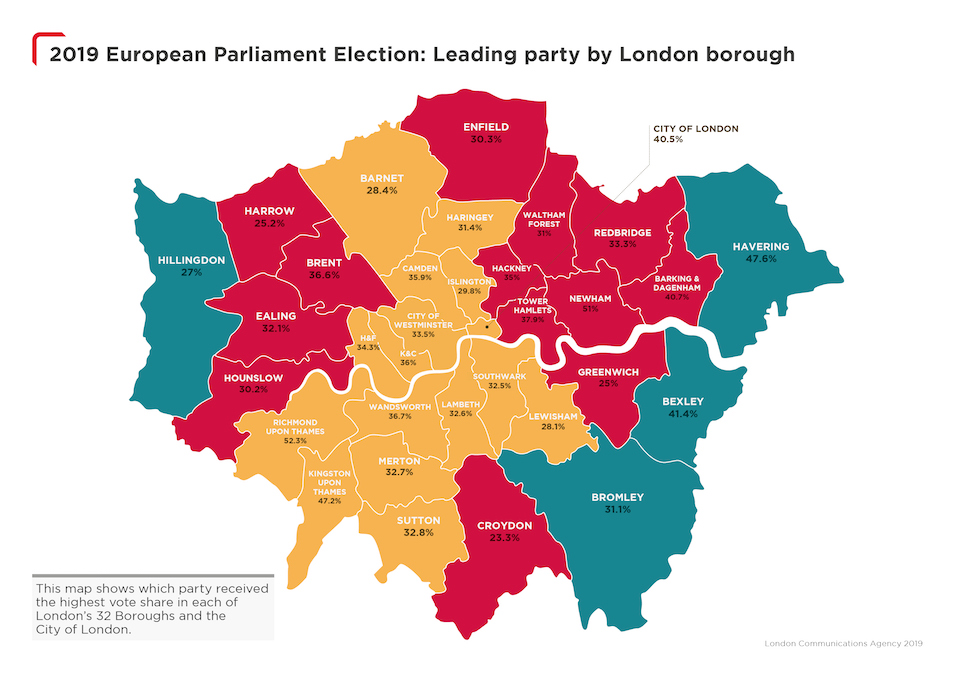

And this map shows which party came first in each borough.

Note the massive rise in support for the Liberal Democrats (up a stonking 20 per cent to 27.2 per cent) and the Greens (up to 12.5 per cent). The success of the Brexit Party, even in London, is remarkable. At nearly 18 per cent, Nigel Farage’s new party more or less replaced UKIP’s 17 per cent share of the vote in 2014. Labour’s fell nearly 13 per cent to leave the party second in the capital on 24 per cent. As for the Tories, they fell to a staggering fifth place in London, down over 14.5 per cent at just under eight per cent.

Local vignettes illustrating how much this election played havoc with established voting patterns include:

- Labour coming second to the Lib Dems in traditional strongholds such as Camden (Keir Starmer’s patch), Islington (Jeremy Corbyn’s home field) and Lambeth (including every ward in Brexiter Kate Hoey’s constituency).

- Similarly, the Tories coming fourth in Kensington & Chelsea, Wandsworth and Hillingdon (Boris Johnson territory), and fifth in Croydon (historically a key swing borough between Labour and the Tories). In fact, as Baston says, the Tories didn’t manage even a third place finish anywhere in London, including true-blue boroughs like Bromley and Westminster!

- The Libs Dems came first in nearly half of London’s 32 boroughs and in the City of London, as the map above shows. We will forever remember their sweeping win as “the yellow poodle” (squint a bit and look from North to South London on the map above, and you will see what we mean).

The end result in terms of the capital’s eight MEPs is a significant change, with the Conservatives losing both their seats, the Lib Dems now holding three where before they had none, Labour’s team of four now halved to just two, the Greens with one seat and the Brexit Party on two, doubling what UKIP won in 2014. Here is the table comparing the 2014-19 class and the new class.

What might this mean for London going forward?

Although at the time of writing the bookies were quoting 7/4 that we will have a general election later this year, the next scheduled election test for the capital is the May 2020 Greater London Authority elections for the London Mayor and the 25 London Assembly Members (AMs), often called simply the London Elections. They are less than a year away and a lot will happen between now and then to influence the electorate’s mood. As Lewis Baston says, it always dangerous to apply a set of results from one election to a different one, especially when it is also an election of another kind with different issues at stake. In addition, we don’t yet know for sure if the Brexit Party or Change UK will take part in the London Elections.

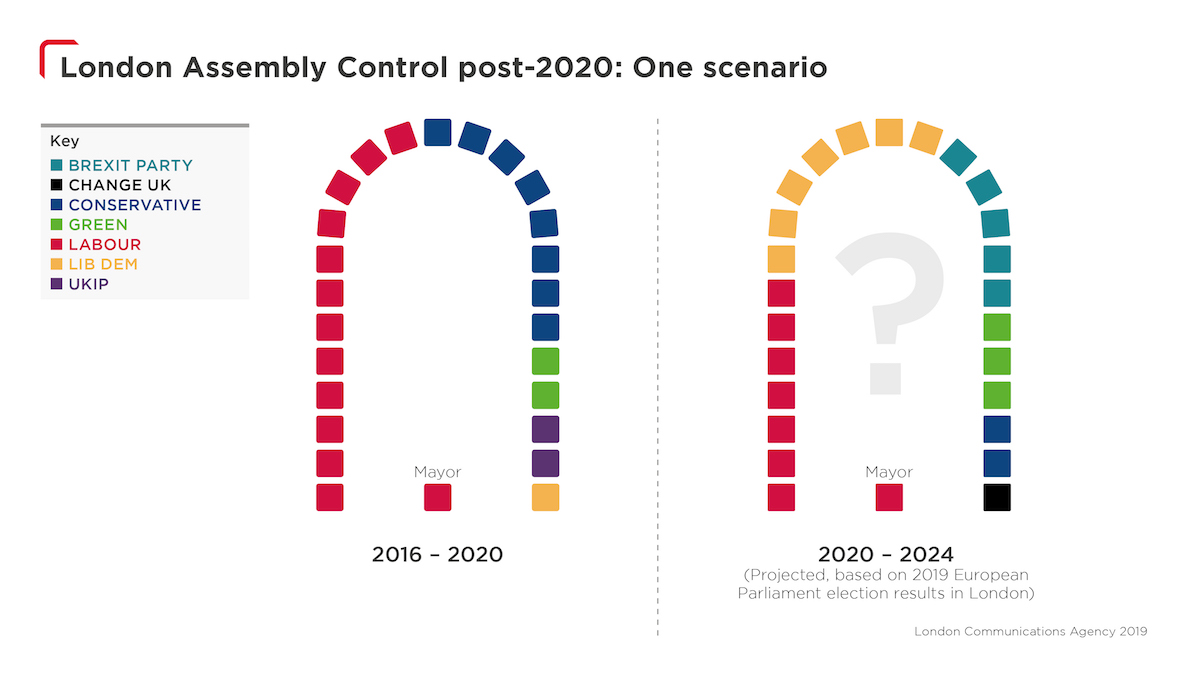

Even so, given the dramatic results of the European Parliament contest in the capital, it is worth considering how a repeat of the vote shares each party secured in them might translate into Assembly seats and the outcome of the mayoral race. This may just be a bit of electoral psephology fun, but we thought it worth a go.

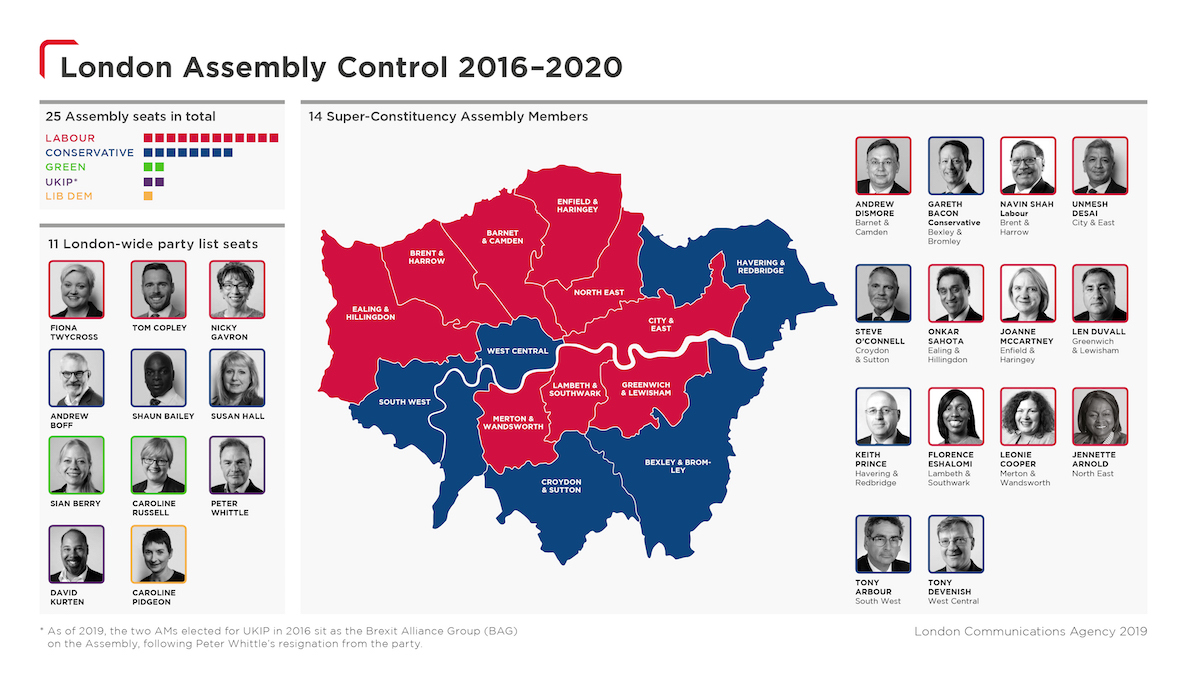

Londoners can cast up to four votes in the GLA elections: first and second preferences for Mayor; a first past the post vote in one of the 14 London Assembly “super constituencies”; and a proportional representation-style vote for 11 “top up” London-wide seats. This range of options does, of course, encourage multiple voting across political parties, a factor we have seen in the previous five sets of GLA votes, which complicates matters further (and could get Alastair Campbell get into even more trouble). See below a map of the 14 London Assembly seats and the current line-up of AMs.

The London Assembly – does anyone care?

For most Londoners, the Assembly is still a bit of a mystery 20 years after its creation by the Greater London Authority Act 1999. It’s a bit like a parliamentary select committee in that its job is, first and foremost, to scrutinise the Mayor and his functional agencies. The government is currently reviewing its effectiveness and purpose, but in recent months we have seen the Assembly doing quite a robust job and generating headlines, most notably through its work on Crossrail, Transport for London’s budget and the Garden Bridge. Additionally, hidden away in the GLA 1999 Act, is the power the Assembly has to vote down the Mayor’s annual budget.

This can only be exercised if a minimum two-thirds majority of the 25 members – that is effectively 17 AMs – opposes it. Currently, Labour holds nine of the 14 constituencies and a further three seats from the top-up list, giving the party a total of 12 seats and leaving the others with 13 between them – four less than they would need to block a Labour Mayor’s budget.

Is it possible, in light of Labour’s European elections performance in London, that they could lose at least some seats on the Assembly next year? The answer is clearly yes. For example, they could lose three of their nine constituency seats to a resurgent Lib Dem campaign. All six boroughs comprising the “super constituencies” Barnet & Camden, Lambeth & Southwark and Merton & Wandsworth saw the Lib Dems come first in the Europeans. And before Labour activists pile in here, we would remind them that only ten years ago (between 2006-2010 in fact) Camden and Southwark were local authorities run by Conservative-Lib Dem coalitions. In addition, if Labour’s share of the vote was again as low as 25 per cent, it’s unlikely that they would retain all three Londonwide top-up seats they currently hold.

The loss of four Assembly seats would reduce Labour’s total to eight and lift the combined total of all the other parties to the 17 they would need to stop the Mayor getting his budget through. So if Sadiq Khan were re-elected – which still appears likely – he could nonetheless find himself in the unenviable position of seeing his budget overturned by an alliance of AMs from parties other than Labour.

How many of those might be Conservatives? The Tories currently hold the other five constituency seats and have three top-up AMs, giving them a total of eight seats altogether. Based purely on their lacklustre eight per cent last month, it’s not inconceivable that they could lose all five of their constituency seats in contests held under the first past the post system. Three of them could very well be won by the resurgent Lib Dems in West and South London (South West, West Central and Sutton & Croydon), while the other two could fall to the Brexit Party in the east (Havering & Redbridge) and south east (Bromley & Bexley).

The Tories could end up depending on Londonwide list top-up seats to have any representation on the Assembly at all, and they would have plenty of competition from an emboldened Greens, who will be looking to increase their representation from two to three, and from the Lib Dems, who add to their present one list seat, depending on how they fare in the constituencies. As for the two newcomer parties, Change UK might just scrape one and if the Brexit Party maintained its vote share it could pick up at least two in addition to a possible pair of constituency seats.

Clearly several large assumptions underpin this hypothesis, the biggest being that we will still be dealing with Brexit come next May and that voting in London is again fractured, including to the advantage of the Brexit Party. However, based purely on the European election result, it is perfectly possible to imagine a London Assembly made up of seven Lib Dem and Labour AMs, five from the Brexit Party, three Greens, just two Tories and perhaps one from Change UK. It would be the most the most fragmented London Assembly we have yet seen.

And so to the Mayor

So what about the mayoral candidates? Sadiq Khan is still favourite to win the mayoral election, despite his party’s recent slump. His popularity rating was a reasonable +6 in the most recent YouGov poll for Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) and he was still polling strongly compared with the other known mayoral candidates. He has also consistently supported Remain, suggesting he will outperform his party as he did in 2016. We doubt his office will be that worried by Labour having come second to the Lib Dems in the European elections. But who might come second to Khan?

The poll for QMUL put the Lib Dem candidate Siobhan Benita in fourth place, behind both the Green Party and Tory runners. But judged on the basis of the European election result, she is clearly Khan’s closest challenger. A recent opinion poll showing her party in the lead nationally seemed to confirm this as something to at least be prepared for. The Lib Dems have fallen back in recent mayoral races, and if they recovered to second it would be a big shock for the Conservatives, especially as their London members selected Shaun Bailey with an eye to appealing to as broad a voter base as possible.

Since we’ve looked at many a counterfactual in this article, we might as well ask the question: could Khan actually lose? The fragmented nature of the European election result in London does raise at least the possibility of the first preference margin being close, in which case the second preferences of voters whose first choice didn’t make the run off could prove decisive.

Strongly pro-Remain voters who reject Khan because of his party’s Brexit stance have candidates from two unambiguously pro-Remain parties they can give their first and second preference votes too. If, for example, Benita rather than Khan took a lion’s share of Berry supporters’ second preferences, she could get a big boost (and vice versa, if Berry made the run-off). Clearly, the Mayor will feel the need to push his Remain-even-if-it-means-another-referendum message as hard as possible.

That said, a number of other issues will come into play when Londoners go to the polls next May. Khan’s record, especially his performance against his 2016 manifesto pledges, is one issue to watch – the Conservatives are gunning for him on this front. Others will include the state of London’s economy, whether the UK has actually exited Europe and how, and, of course, whether there has been a general election beforehand or perhaps even on the same day as the London elections.

Three final thoughts. Could the voting patterns in the European election encourage a high profile, non-partisan (and possibly young) person to throw their hat into the mayoral ring? To stand, they need only a petition with 330 Londoners’ signatures and a £10,000 deposit. And if Brexit drags on, could we also see an high profile pro-Leave candidate running? In both cases, an “anti-politics” candidate could be the bearer of a powerful message to disaffected voters. Whatever conclusions you draw from the European election results, they have undoubtedly unnerved both the two main parties across the country. Their next definite test is in the capital – 11 months and counting down.

Robert Gordon Clark is chairman and partner of London Communications Agency. Tony Travers is professor of government at the London School of Economics and director of LSE London. Thanks to Stefanos Koryzis, Emily Clinton and Thomas Salter at LCA for all their help with this article, in particular its visual content.