In the beginning, it felt so right. True, historic London food markets, fixtures of the capital’s identity for centuries, would be moving from its heart to its outskirts. But relocations had happened before. And if there was to be a great migration of the scores of traders selling fish, meat, fruit and vegetables to shops, restaurants and others across the city, what better destination than an old Thames dock site south of Dagenham, a town hungry for economic renewal?

When the plan was made public, in April 2019, excitement was expressed about the City of London Corporation, owner of the Smithfield meat market in Farringdon, Billingsgate fish market in Poplar and the New Spitalfields horticultural produce hub in Leyton, consolidating all three in one place.

Catherine McGuinness, who at that time chaired the City’s policy and resources committee and, as such, was its political leader, said the selection of the Dagenham site showed the corporation to be committed to the markets’ future, with a “number one priority” of maintaining “a top-quality market environment serving London”.

James Tumbridge, chairman of the corporation’s markets committee, hailed “another positive step forward” towards “a vision for a food centre suitable for London’s future”.

None of this meant a deal was done. The City’s announcement stressed that a public consultation was yet to come and that the 42 acres at Dagenham Dock, now officially the City’s “preferred site”, were at that point no more than “broadly acceptable” to the markets’ traders.

Even so, key ingredients were in place, not least the City owning the land in question. Previously the setting for a coal-fired power station, it had been purchased in December 2018 with the declared view of moving the three markets there – a large step forward in project that had long been in gestation.

There was anticipation in and around Dagenham, too. In November 2019, I visited the then local MP Jon Cruddas as he campaigned in his marginal seat for the following month’s general election. We talked about how the area in some ways resembled parts of Britain that had come to be called “left behind” due largely to de-industrialisation.

In Dagenham, the closure of the Ford Motors production plant, very close to the potential markets site, had had a big, long-term impact. For years, there had been talk of revitalising the Thames Gateway, a long stretch of riverbank reaching from Lewisham and Tower Hamlets into Essex and Kent. Maybe talk would soon be turned into action. “It’s more concrete, it has more potency than before,” Cruddas said.

Barking & Dagenham Council was enthusiastic, too. And in March 2021, its planning committee approved the City’s outline application. Darren Rodwell, the council’s charismatic leader, hailed “great news for the borough” with the prospect of new jobs and training opportunities. The founding of a food school on the site was proposed, where future generations of butchers and fishmongers would be taught.

The pandemic had been going for a year, wreaking havoc with the construction sector. But that did not appear to be derailing what the City termed its market co-location programme (MCP). And 18 months later, on 17 November 2022, it announced that it had “approved plans for a major regeneration programme” which would see it “invest nearly one billion pounds directly into Barking and Dagenham to regenerate 42 acres of industrial land into a modern, sustainable wholesale food market, stimulating the local economy and ensuring resilience in the food supply of London and the southeast”. The new market was expected to open before the end of 2028 at the latest.

By then, and since May 2022, McGuinness had been succeeded as the City’s leader by Chris Hayward, a former deputy leader of Dorset and Hertfordshire county councils with a background in property businesses. He greeted what he called “a major milestone in an ambitious programme with economic growth at its heart, something our country so clearly needs”.

But things began to change. And in November 2024, exactly two years after the Dagenham Dock plan had been glowingly approved, the City said it had been abandoned. What was more, it would be closing both Smithfield and Billingsgate, ending its centuries-long association with them. It pledged to help them find new bases for the meat and fish businesses, but their futures remain uncertain.

What changed? Could the outcome have been different? And what does it all mean for London?

WHAT HAPPENED? THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW

For Chris Hayward, the reason for the collapse of the Dagenham Dock plan is, in the end, straightforward – the City could not afford it.

On the same day in 2022 as the City announced its approval of the move, 17 November, a special meeting of the Court of Common Council – the City’s equivalent of a full borough council meeting – was held, starting early in the afternoon.

The court considered the “markets co-location programme”, as it was termed, but did so in private – away from the public and the press, as is often the case with local government matters when sensitive financial matters are involved. But confidential minutes of the discussion, which later came into my hands, describe it as having been approved “as a major project with a budget envelope of £577 million”.

This figure, the minutes state, excluded “sunk costs” – meaning expenditure already made that cannot be recovered – of £164 million, bringing the total expected to be spent on the programme overall up to £741 million. And the relevant section referred only to Smithfield and Billingsgate. New Spitalfields was not built in to the Dagenham Dock project at that stage. Quoted by the Barking & Dagenham Post, a spokesperson said that although the City still intended this to happen at a later date, it was “not able to give a timeline”.

The minutes also refer to an additional, unspecified, sum in compensation relating to the Poultry Market section of the Smithfield building, saying this had already been approved. They further note that corporation officers would be looking into acquiring another, much smaller piece of land, around 4.78 acres of it, to the south of the Dagenham Dock site. These items, added to the £741 million, perhaps explain the mention in the press release sent out on the same day of “nearly one billion pounds” of City money going into Barking & Dagenham.

Interviewed by me at the Guildhall near the end of May this year, Hayward put the original estimate for the project at “around £600 million” – very adjacent to the £577 million “budget envelope” of November 2022 – and said this had, of itself, “ended up at about a billion pounds”.

He explained that by the time he decided to pull the plug, the City had already “set about spending a few million” on remediating the Dagenham Dock site – cleaning it up before construction work could start. And then came the costs explosion that has helped debilitate the construction sector across the capital. “Inflation took off, construction inflation became huge,” Hayward said. Result? “The bottom line is that I arrived at the view, as the leader of the corporation, with the support of my policy committee, that the Dagenham Dock site had become unaffordable.”

He went to set out why he wouldn’t countenance one possible option for continuing to finance the project. “To have been able to afford it, I was told by officers at the time, would have meant selling a substantial chunk of our investment properties,” he said. This was not an acceptable to him: “We are not a private company. We are not about profit and loss here. We are stewards of all sorts of amenities, not just across the Square Mile but right across London, and many of those, particularly the cultural ones, we subsidise as well, as you always have to do with culture, etcetera.”

Hayward described the investment properties, many of them located on some of the most valuable and sought after real estate on Earth, as having been “bought over a thousand years” and “used to fund everything we do”. They were not to be disturbed. “My view was, frankly, not on my watch. You can only sell the family silver once.”

The wider context was that all of the City’s other capital projects were becoming more expensive too. Some major ones were already underway, notably an ambitious “justice quarter” off Fleet Street on Salisbury Square, comprising new law courts, a new headquarters for the City of London Police and a commercial building to help the numbers stack up.

Then there was the forthcoming new London Museum. Formed by the City as the Museum of London in 1976, it had, ever since, occupied a purpose-built site on bomb-damaged land on London Wall, forming part of the Barbican complex. In 2015, the museum’s director, Sharon Ament, made known a wish to move into a part of Smithfield – the General Market building, that had fallen vacant. Since then, though co-funded with the Greater London Authority, the £250 million price tag for its ambitious renovation had grown as well.

“If we had proceeded on the basis of the increased costs of the Dagenham development, we would have been, in my judgement, overstretched on our ultimate capital programme,” Hayward said. His judgement, in other words, was that had the City gone ahead with the markets scheme, those others that were already in progress might have been in danger of running out of cash.

But Hayward stressed that the decision wasn’t based only on his assessment of financial prudence, because the views of the market traders were important to him too. His starting point was that, from the beginning, those of Billingsgate and Smithfield were eager for change and open to suggestions.

Billingsgate’s current premises are not particularly old. The market takes its name from the wharf on Lower Thames Street where a rudimentary fish market began in the 16th Century. Established in law in 1698, it went through various enlargements and improvements before moving, in 1982, to its present, purpose-built complex right next to the A1261 and close to the twin mouths of the Blackwall Tunnel – good road transport links for the lorries and vans that still daily converge on the market from as far afield as Scotland and Cornwall, with others bringing overseas imports from Heathrow. The site was yet to be overshadowed by the signature glass towers of Canary Wharf on the other side of the old North Dock. But that would soon come.

Smithfield’s origins are even more ancient than Billingsgate’s. Livestock has been bought and sold at the location since the 10th Century, on what was known as the “smooth field” at the edge of today’s Square Mile. It survived the Great Fire of 1666 and in Charles Dickens’s time was a huge, noisome arena for the slaughter and exchange of beasts delivered to it, often from far outside the capital. Bill Sikes frogmarched Oliver Twist across grounds described by Charles Dickens in his novel as “nearly ankle-deep with filth and mire”.

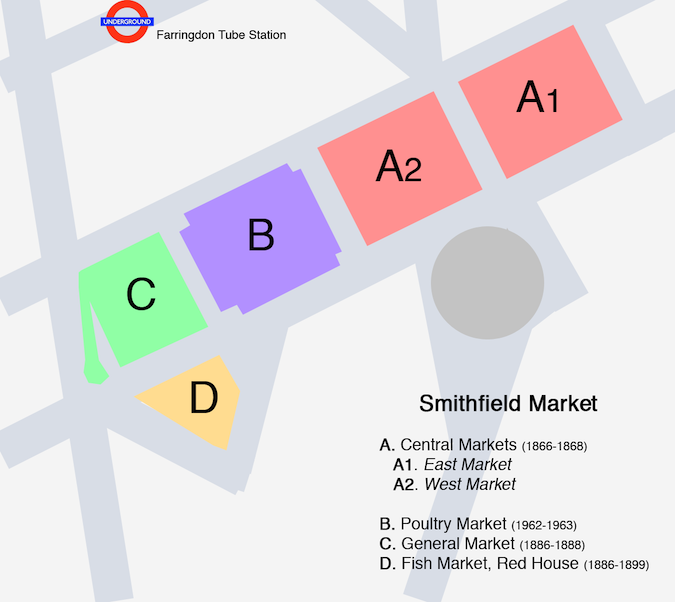

The market in that form was closed soon after Oliver’s fictional ordeal, and a bespoke, Italianate Central Market building, designed by City architect Horace Jones – whose later achievements would include a Thames-side Billingsgate HQ that also still stands, and Tower Bridge – was completed in 1868, with East and West sides, to contain the new, wholesaling version. The adjoining Poultry Market and General Market buildings were added to it in the ensuing decades, the former rebuilt in the 1960s after a fire. Together, they have grandly occupied a long, rectangular space between, on one side, Charterhouse Street and, on the other, West Smithfield and Long Lane ever since, augmented, also in the late 19th Century, by an adjacent fish market and cold store (image below from Wikipedia by DarTan).

The meat trade contracted after World War II, and by the 1990s the General Market building, which the London Museum is currently settling into, had fallen into disuse. Even so, the Smithfield traders wanted a future that was secure and bright.

Hayward said the City could have decided to leave things as they were with both Smithfield and Billingsgate, bar spending what was necessary to meet health and safety requirements. However, he went on, the traders “didn’t want that. They said to us, ‘we want modern buildings. We can’t go on where we are. We can’t expand our businesses where we are’.”

Eventually, Hayward said, the traders themselves concluded that it was time to end the markets’ ancient link with the City: “They said to us, very politely but very firmly, the time has come when we no longer really want you as our landlord, we want to do our own thing. The end of the era, if you want to call it that, was right for them as well as right for us. This was not us bullying them or pushing them, or saying we don’t want you anymore. It was them saying to us, ‘we want to be set free’.”

WHAT HAPPENED? OTHER VIEWS

Not everyone is happy about Chris Hayward’s decision or satisfied with his reasoning. Some in Guildhall circles either don’t accept the matter was handled well in the City’s corridors of power, don’t find Hayward’s financial argument compelling, or both. Others, more distant from the negotiations and ruminations, were upset by the very idea of the historic City of London markets coming to an end.

Peter Acton, who launched a petition to stop the markets’ closures, described himself as, “Just a citizen of the UK who cares about protecting our heritage and the livelihoods of the great workers at Smithfield and Billingsgate markets”. A former Londoner, now resident in Cardiff, he also expressed concern about “food security, including those of lower incomes who rely on these wholesale markets”. As I write, over 40,000 people have signed.

For some of its critics, the City’s about turn exposed ingrained attitudes about what constitutes sound financial investment and, on Hayward’s part, a shortage of commitment when push came to shove. One view is that the Guildhall’s financial officer class was simply not persuaded that putting a large sum into quite a complex development project well beyond the Square Mile’s boundary – one that would yield significant returns in the form of rents only over the long term – represented good value for money. Potential benefits in terms of safeguarding important food businesses and creating new jobs in a part of the capital greatly in need of them are seen as having been not rated very highly.

Another complaint is that the City’s decision-making processes were – and are – both glacial and opaque. From that perspective, the general proposition of the markets move had been considered and backed many times over the years, but institutional inertia had prevented speedy action which, had it been taken, would have seen the project get well underway before development sector costs went through the roof. And part of the reason for that slowness, the argument goes, was that, backstage, small “p” but large “I”, political influence of a largely unaccountable group within the City’s corridors of power was never sold on the idea, resulting in unduly tight financial constraints on those seeking to sort out the details and practicalities of the Dagenham move.

Shifts in the Guildhall’s institutional architecture are seen as having been problematic, too. Renamed the markets board, the markets committee was reduced in size and had its terms of reference re-written, giving it less power. This was resisted on the grounds that the markets’ relocation should not be seen as just another commercial property investment – after all, like those of local authorities all over the country, the City’s markets are run for public benefit and subject to national government regulations, meaning they need to be treated differently at local government level. But the effect of the change from committee to board was, it is said, to marginalise the body and exclude it and its expertise from key decisions.

The special status of markets in law means that relocating them needs the consent of Parliament. Securing this entails depositing a Private Bill – not to be confused with a Private Members’ Bill – which has to be approved by both the Commons and the Lords. During the legislative passage of such a bill, individuals or organisations deemed “directly and specially” affected by it are allowed to petition against it.

In February 2023, it emerged that Havering Council, Barking & Dagenham’s neighbour to its east, had done so. It was worried about the implications of the Dagenham Dock plan for Romford Market, four miles away. The council drew on another piece of ancient legislation, a Royal Charter granted by Henry III in 1247, which prevented any other market being set up within a distance that could be covered by a sheep – in reality a herd of them being driven to market, and not in a motor vehicle – in the space of a day. Four miles, apparently, would be comfortably within a driven sheep’s normal range.

A rather niche objection, perhaps. But Havering’s interest was valid. The council’s point was that the Private Bill did not explicitly limit Billingsgate and Smithfield to selling wholesale, meaning that ordinary shoppers would be able to buy fish or meat from them, as indeed they can at present. Seeing this as a potential threat to Romford Market, the council asked for a clause to be added to the Private Bill forbidding retail sales.

Meanwhile, negotiations with organisations representing the traders, the Smithfield Markets Tenants Association and the London Fish Merchants’ Association, continued, the former led, as it had been for several years by Greg Lawrence, who was also a City Common Councillor and a member of the markets committee.

There were discussions about the design of the buildings envisaged for Dagenham Dock. A key thing for the traders was that their core activity could continue to take place within a single open space at ground level – if you’re lugging large animal carcasses or big boxes of fish around, you don’t want to be crowding into lifts or dragging yourself up flights of stairs. There were, in Hayward’s words, “several iterations” of a design labelled “10b”.

By the spring of 2024, it was plain that the tide had turned. In May of that year, announcing Chris Hayward’s re-election as policy and resources chair, the City highlighted the Salisbury Square and London Museum projects, but made no mention of the markets. And in the same month, the corporation took on as a consultant, Theresa Grant, a highly experienced senior local authority officer. Recent jobs Grant had completed included sorting out financial problems at Liverpool City Council and the (now-abolished) Northamptonshire County Council. With such experience to draw on, she was well-equipped for her latest challenge.

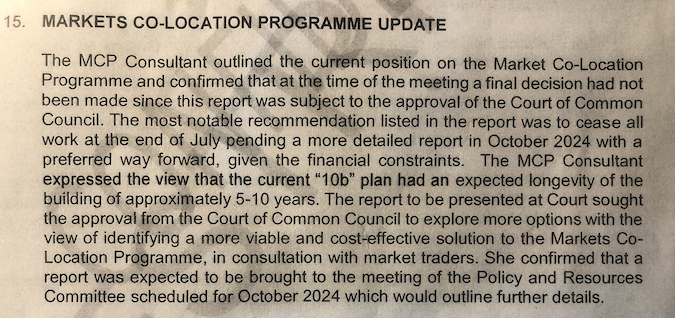

Grant made speedy progress. Confidential papers relating to a markets board meeting – by then chaired by Henry Pollard – held on 22 July 2024 include an account of a “markets co-location programme update” by Grant, described as “the MCP Consultant”. This referred to a report “subject to the approval of the Court of Common Council” whose “most notable recommendation” was “to cease all work at the end of July pending a more detailed report in October 2024 with a preferred way forward, given the financial constraints”.

The account also says Grant expressed the view that “the current 10b plan had an expected longevity of the building of approximately 5-10 years” and that approval by the court was to be sought “to explore more options with the view of identifying a more viable and cost-effective solution to the Markets Co-Location Programme, in consultation with market traders”. Members, the account adds, “asked for further clarification of what was meant by 10b”.

The Common Council held its next court on 25 July 2024. Its agenda lists a non-public section to include a “markets colocation programme delivery review update”. And by the time the markets board met again, on 3 October 2024, the Dagenham plan was as good as officially dead.

In terms of committee members, the meeting was so poorly attended it was inquorate: of its 14 councillors, only Pollard, his then deputy (and now successor) Philip Woodhouse and two others are listed as having been present. Among councillors to send apologies were Greg Lawrence. A co-optee, Tony Lyons, chairman of the London Fish Merchants Association, did the same, as did Michael Cogher, the City’s deputy chief executive (and City comptroller and City solicitor), who sent a representative. However, markets director Ben Milligan is named as having been there, along with Grant and 16 others, including ten of the City’s surveyors and other staff.

A document marked “confidential” and headed Agenda Item 19 says Grant gave a verbal update on the MCP in which she “confirmed that she had held a discussion with both Smithfield and Billingsgate traders since the end of July 2024” as well as considering a number of options for the future of the markets, including a “condensed version” of design 10b on Dagenham Dock. However, the account of the update adds that the traders “were still not in favour of a two-storey building design” – a reference to 10b – and “not satisfied either with a potential move to Dagenham Dock”.

It is recorded that one board member, who isn’t named, regarded the lack of a resolution that suited all parties several years after the project began to have represented “a failure for the City Corporation from a governance perspective”.

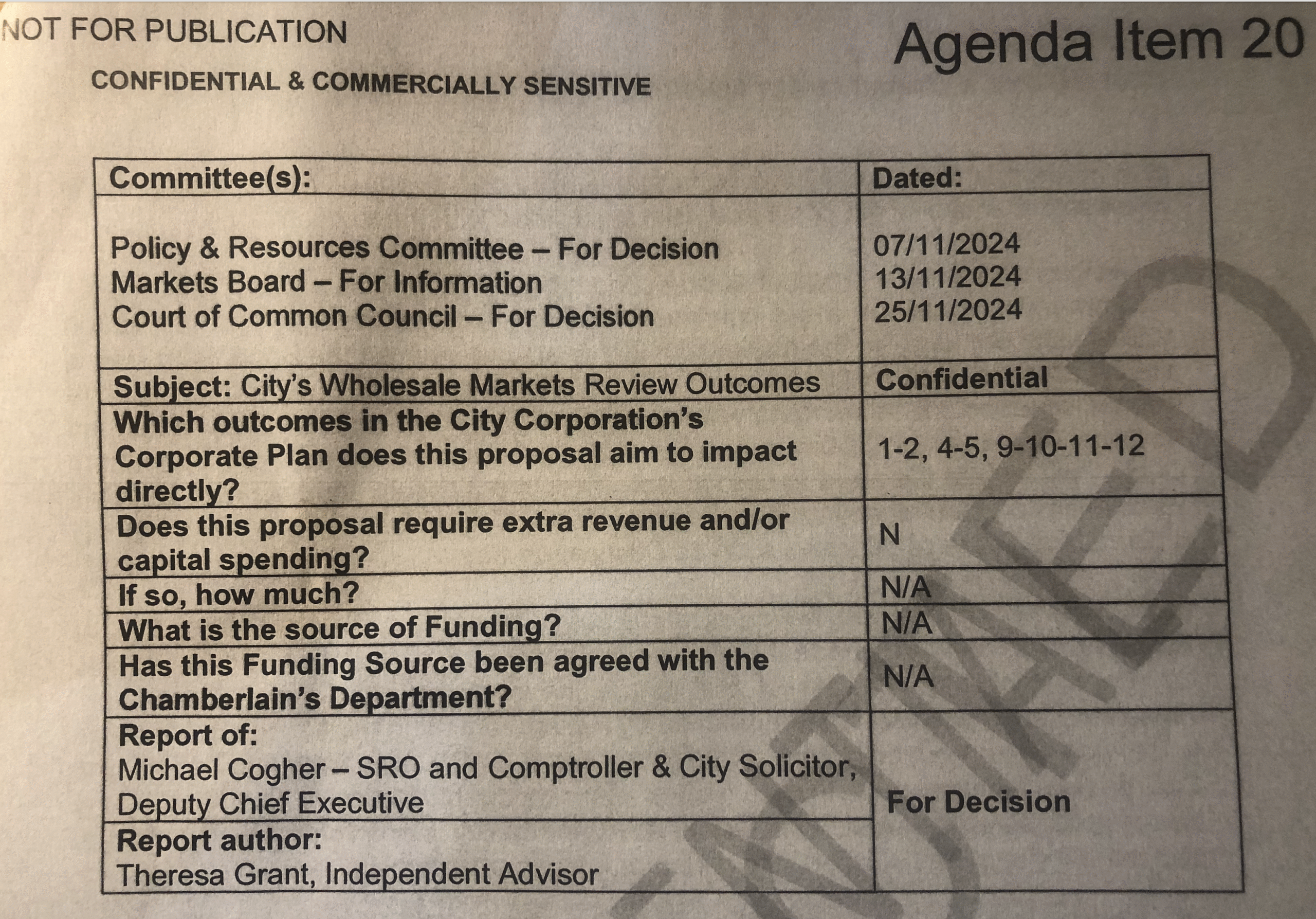

The document also states that, in response to a question from Pollard, Grant confirmed that a report was due to be submitted to the policy and resources committee meeting due on 7 November 2024 and to an “informal” Court of Common Council gathering scheduled for the same day. Also among the confidential papers that came my way, headed Agenda Item 20 and “not for publication”, was a copy of what appears to be the report itself.

THE CONSULTANT’S VIEW

It was described as the “report of” Michael Cogher, but authorship was attributed to Theresa Grant, who was described as an “independent advisor”. At the top, it stated that the policy and resources committee would take a decision about the report on 7 November and the formal full court would do so on 25 November. The markets board would see it on 13 November, but only “for information”.

The report’s opening summary got straight to the point:

“This report sets out a recommendation for City of London Corporation (CoL) to support two collective compensation payments to the traders of both Billingsgate and Smithfield markets, for them to vacate the current market sites and continue to trade in a location of their choice.”

Doing this, the summary continued, “would ensure continued food security for London and the South East” and enable the City to submit a new Private Bill to Parliament in order to “de-marketise” and “achieve vacant possession” of the sites thereafter. These would then be used for “new, mixed-use developments” with the emphasis on housing (in the case of Billingsgate) and culture (in the case of Smithfield, complementing and augmenting the museum).

The calculation set out in Grant’s report was that these projects would deliver close to around two-thirds (“c63%”) of the “gross value added” – a measure of the value of goods and services produced by the two areas – aspired to in the original business case for the relocation, with the Dagenham Dock site still having the potential to provide the rest of it if a “creative solution” for it could be found. Financially, the City would come out even, more or less, and also have “no further liability or responsibility” for running the markets “or the costs and risks” associated with them. Those costs were put at about £1 million “accruing year on year across the two markets”.

Members were asked to approve the “new strategy” of ending the City’s involvement with the markets, bring the markets co-location programme to an end and ask “an external agency” to develop “a media and stakeholder engagement plan” in order to “manage key messages”. They were also asked to approve securing the traders’ support for the new Private Bill that would be needed, “noting an upfront payment is required” to enable them to find new places to do business and “help protect food security”.

The document sets out the background to Grant’s recommendations, recording that the MCP had originally included New Spitalfields as well as Billingsgate and Smithfield going to Dagenham Dock, but that “due to trader unwillingness to accommodate a stacked solution” New Spitalfields had had to be excluded. It says the business case agreed by the City on that basis included “an original cost of £841 million” and foresaw “cumulative GVA for the UK to 2049” of approximately £14.5 billion.

It goes on to state that what it terms “the Dagenham Docks Option 10B” had already been deemed “unaffordable” back in July 2024 by the policy and resources committee and the Court of Common Council, and that this had been due to “global events” such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and “abnormally high construction cost inflation”. This had meant the estimated programme cost rising to £947 million in all, with £647 million of that to be spent on 10b, which “did not have long term viability” and was therefore “a very poor investment” – a conclusion which, the document reveals, was reached on the advice of financial services company Deloitte and real estate services firm CBRE.

The background section of the main report continues with Paragraph 3, which says as follows:

“In light of these challenges, CoL [City of London] tasked the Independent Consultant with identifying a solution that delivered the maximum social and economic benefits, satisfied the traders, offered continued food security, delivered the desired jobs in LBBD [London Borough of Barking & Dagenham] and provided a solution that was affordable to CoL. Specifically, this included completion of further work on alternative options, including formal negotiations with market tenants.”

In its next paragraph, the report details a previous compensation package agreed with the Smithfield traders (SMTA) back in 2022. This, the report says, was to recompense the Smithfield traders for moving out of the Poultry Market by August 2023, provide vacant possession when the theoretical 10b Dagenham Dock building was ready for them, and an agreement to “take up leases” there.

Of that previous compensation package, the report says “CoL approved payment of £30m to SMTA on signing the deal” plus “£70m on vacant possession of the Poultry Market, with the remaining £15m to be paid as a relocation package” after the traders had taken up their Dagenham Dock leases. The City had also agreed to pay “reasonable professional fees capped at £850k”.

The first two elements of the agreement, totalling £100 million to the STMA, had already been paid, the report continued. And the £15 million for taking leases at Dagenham would have to follow, even though the leases were not going to be signed, because, in the words of the report, “none of the conditions not to pay over the funds have been satisfied”. Grant’s report went on to summarise “tenant negotiations” that had begun on 31 July 2024 and continued “in parallel” with consideration of the “various options” for their futures.

Eventually, the “various options” were narrowed down to two: Billingsgate and Smithfield staying where they were, or the traders agreeing a compensation package to “go their own way”. The City, says the document, “made it clear that the option of a light refurbishment, giving the [existing] buildings another 10-15 years was suboptimal”. In plain English, that means doing the old buildings up a bit would, though “deliverable and affordable”, be a poor use of the money needed for the job and would not, of course, release the sites for the housing and cultural uses the City had in mind for them.

The document then provides some candid insights into how discussions about the “demarketisation” compensation option proceeded. “Both sets of traders opened with excessive requests,” it says: “Smithfield at £275m (plus the £15m from the previous SMTA agreement) and Billingsgate at £300m”.

Several months of “intense negotiations” followed, says the document, resulting in the compensation requests being brought down to “more manageable and affordable levels”. A “best and final offer” from the City is recommended as “the lowest figure that can be achieved”. The size of that “best and final offer” is not revealed.

The report then goes through the “various options”. Dagenham Dock is dispensed with in just three paragraphs, one of them stating that the idea of moving “between 40% and 70% of tenants” there had been explored and dismissed.

Moving just over half of the Billingsgate and Smithfield traders up to Leyton, to share space with New Spitalfields, was looked at and turned down. So was accommodating some of them at New Covent Garden, the “New” of its name bearing witness to a previous relocation of a famous London wholesale market from its original home, in its case south of the Thames to Nine Elms. Many paragraphs, covering four pages, were devoted to why “in-situ” options for Billingsgate and Smithfield, leaving them on their current sites, were not recommended either.

That left the preferred, two-part solution: to “de-marketise” and pay the meat and fish traders compensation. To “de-marketise” would be to enable the Grade II listed Central Market, East and West, to be “sensitively reimagined” as “an international cultural and commercial destination”, remove “continued disruption” to the new London Museum works and “release the site for a considerable capital receipt” (translation: a lot of money). The report also said that the recommended option would – through a complicated formula for assessing profitability – reduce the risk of Parliament imposing “a more punitive compensation package” when it considered the new Private Bill.

In return for the compensation package, the traders would be “legally locked into” writing letters in support of the Private Bill, giving evidence to that effect in Parliament if necessary and supporting a “food study analysis”, which would consider London’s long term food security. They would also be locked in to receiving their compensation in three parts, the first upon signing the legal agreement with the City, the second upon the Private Bill getting Royal Assent and the third upon moving out.

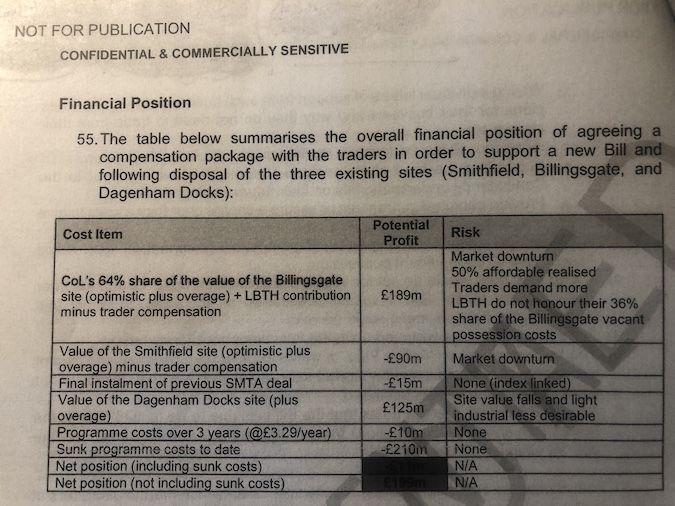

In a table, a projected “overall financial position” should the compensation package be agreed and the Smithfield, Billingsgate and Dagenham Dock sites sold, is set out. It foresees a potential profit for the City of £189 million from a 64 per cent share of the proceeds from Billingsgate minus the fish traders’ compensation.

For Smithfield, it anticipates a loss of £90 million once compensation is subtracted from the sale price. The value of the Dagenham Dock site is put at ultimately £125 million. Overall, with the outstanding £15 million for the Smithfield traders thrown in, the City would be £11 million worse off if the £210 million “sunk costs” were taken into account and £199 million to the good if they weren’t.

Looked at another way, not refurbishing the markets would mean not spending £609 million, and ending the MCP would mean not spending £637 million on moving the markets to the Dagenham Dock site and instead getting a potential £125 million for selling it.

That “combined position”, the report says, would mean well over £700 million being available that otherwise would not have been. This, it continues, “will negate the need to sell valuable investment assets and help restore the City’s Estate financial sustainability”.

Which brings us back to what Chris Hayward said about selling the family silver. It also brings us back to the question to which different people have different answers. Should things have been done differently?

THE FUTURE AND THE PAST

If you haven’t been to Smithfield or Billingsgate markets in the very early morning, make sure you do before they’ve gone. In each case, you will witness integral, largely nocturnal, parts of London’s workings as a human society – mechanisms of production, distribution, consumption and exchange that convey food from far-off fields and seas to the city’s shops, restaurants and homes. You can set free your historical imagination. You can also see the case for change.

The Billingsgate building’s exterior has a look that might have turned heads at the time it went up, but hasn’t aged with style. The interior is more engaging: a cavernous cold store with wet floors and individual trader pitches wall-to-wall. It is ethnically various, its fare, multicultural, ranging from eel and haddock to exotic species from overseas.

Famously, East Asian customers are well-represented. A cosy café in the corner offers an array of fish dishes with eggs. The morning I went, customers included a family group, maybe South Korean, devouring a lavish spread, a black couple with a small child and a couple of white traders in their white coats. Outside, gulls perched on portacabins. The HSBC megalith soared. In the Canary Wharf tradition, finding the way in on foot, having travelling by Docklands Light Railway to Poplar, was a complex puzzle to solve.

Smithfield, which I visited earlier on the same morning, is, in appearance, both grander and more tired. Ancient and modern abut in this ancient space, the Elizabeth line station adjoining, the Charterhouse next door. City bollards vie for your attention with a littering of Lime bikes. On the streets, big white vans and more big white coats. Horace Jones’s gracious arches and ironwork endure, but there’s a weariness about the scene that isn’t only due to the early hour.

Venturing into one of the “buyer’s walk” retail arcades, I saw the unit of G. Lawrence (Wholesale Meats) Ltd and 20 more. Women seated in little kiosks tapped nimbly at adding machines. A brown man accompanied by a small brown boy conversed at length with a white man behind the counter, wearing a white coat and matching net trilby. I put his age at around 70. Once he’d finished with his other customers, I asked for a lump of shrink-wrapped Scotch beef to be weighed.

“I thought I’d better pay a visit before you all disappear,” I ventured.

“If it ever happens,” he replied, jotting the price of my purchase on a pad. He knocked a couple of quid off. “The City of London, they don’t know what day of the week it is.”

“So, if I come back in five years, you might still be here?”

“That is debatable,” he said.

Does the City know what day it is? Chris Hayward has made his position clear: the Dagenham Dock plan became too expensive for the City and less and less attractive to the Billingsgate and Smithfield traders; the traders wanted better premises, but a make-do-and-mend approach to their existing ones didn’t enthuse anyone involved and, as Hayward put when we met, “their position matured as time went on”; Theresa Grant had explored all the options and concluded that evicting the traders with their blessing, secured with the help of financial compensation and a promise to help them relocate their businesses under their own steam, was the best path to take.

The decision’s critics, though, remain unimpressed. There is, for example, annoyance over the way the way the enigmatic 10b design was ultimately presented to the traders – that characterisation of it as a “two-storey” or “stacked” proposition, when, in the minds of some of those frustrated by the dropping of the project, floorspace above ground level would, in line with traders’ wishes, only ever have been for administrative functions or the food school, not for trading activity. This framing of the building design choice is seen as an example of, as one person put it, “the case for cancellation” being “clearly designed to lead to a single outcome” based on an over-simplified depiction of the project’s possibilities and finances.

I put that point to Hayward, who responded with a different characterisation. “She’s a highly respected chief executive,” he said of Grant. “She was hired by us to negotiate, right? In the sense that she was working for the corporation, how could she be entirely impartial? Her job was to negotiate an agreement that was acceptable to the two parties.” He went on: “I didn’t want a scenario where she negotiated a deal that the traders said they’d been pushed into, forced into, not given any options etcetera. That was never the purpose, so I think her role in this has been hugely helpful to both parties. And I think the market traders will tell you the same thing.”

Another complaint, not made by all, is that the past leadership of the City’s capital buildings board (like the markets board, formerly called a committee), had an outsize influence, undermining the Dagenham scheme. Its current membership includes Hayward and James Tumbridge and Philip Woodhouse, a champion of the Dagenham scheme. Its job description says it is “responsible for the management and oversight of major capital building projects” and it was, until two years ago, chaired by businessman Sir Michael Snyder, who served as the City’s policy and resources chair from 2003 until 2008.

The more caustic critics of Hayward’s leadership of the City as a whole like to point out that Snyder and Hayward are both freemasons, though only some of those I’ve spoken to who have regrets about what has happened with the markets have aired suspicions that Snyder had a negative or too-strong influence on Hayward. One has made a point of stating the opposite.

There is greater unanimity, though, about the final balance sheet: a historic connection is to be lost and with it, notwithstanding the promise of the new museum at Smithfield, a part of the City’s historic stewardship of Londoners’ common interests; a large amount of money has ended up being paid to the two groups of market traders, essentially, in the end, just for packing up and going away – this after quite a tight hold had been kept on the City purse strings when the re-location appeared to be going ahead.

But whatever the rights and wrongs, the causes and effects, the “de-marketisation” of the Billingsgate site in Poplar and the Smithfield Central Market building, and the severing of the ancient links between the City and the markets is going to take place. The new Private Bill, backed by the Smithfield Market Tenants’ Association and London Fish Merchants Association, was submitted to Parliament on 27 November, 2024. It had its first House of Commons reading on 22 January and is now approaching the committee stage.

In December, James Tumbridge appeared on television to say that around £300 million of private investment had been provisionally put forward to rescue the Dagenham Dock plan, perhaps with twice as much to come. The hope was that these investors would lease the Dagenham site from the City, which would help them to, as Tumbridge put it, “oversee and run it properly”. In theory, this would have secured the traders’ future and enabled the benefits to Dagenham and its environs to be delivered, but in the end it didn’t work out.

Then, in February, the report into the food security implications for London of closing the markets in their present form was published. It found “minimal concern regarding potential disruptions to the food supply chain arising from the relocation of the Traders”. The “media and stakeholder engagement plan” Grant advised was also put into effect.

That explains why I got to interview Chris Hayward. But I never spoke to the leaders of the Smithfield and Billingsgate traders, even though the City provided me with contact details for Greg Lawrence and Tony Lyons in the expectation that both would convey to me their satisfaction with the deal. As none of my emails were answered, we must make do with statements already published elsewhere.

Last November, when the City’s big decision was announced, the BBC reported Lyons expressing distress: “When we heard that Dagenham wasn’t going ahead, it was the worst news we have had for years. We thought we were going to be there for hundreds of years, and it got pulled from under our feet.” The Islington Tribune carried quotes from Lawrence: “There’s no one going to be sadder than me, because I’ve been there all my life, since I was 16 and I’m quite emotional about it.” He was, nonetheless, forward looking: “I think it will be better, really…make no mistake, we’re not silly people, we know this is the best for the tenants and I can understand it’s the best for the City as well.”

And, of course, the market traders are not silly – certainly not when it comes to cutting deals. Those who think the City got itself into a position where the traders could negotiate from a position of some strength make such observations without rancour. “They are traders,” says one. “They’re good at trading. It’s what they do.”

The closing of Smithfield and Billingsgate as City of London markets and their departures from their current sites has been folded into the city’s wider Destination City strategy, which seeks to attract visitors to the Square Mile. The new London Museum is integral to that, while the Billingsgate site, which is in Tower Hamlets, is expected to eventually accommodate up to 4,000 new homes. The City has been keen to stress that large majorities of the traders of both markets have said they want to find ways to stick together, and that a City team is helping them locate potential sites within the M25.

For Chris Hayward, the disposal of the wholesale markets is a component of “a renaissance period” for the City of London, where job numbers have “increased by 25 per cent” since Covid, businesses are “moving back from Canary Wharf” and “we cannot build and develop tall office buildings quickly enough”. For others, the impending end of an era can only be about part the capital’s, indeed the nation’s, soul being lost. Whichever view you take, the story of markets underlines, once again, that London, even in its most timeless respects, is a city always ready move on.

Follow Dave Hill on Bluesky.

OnLondon.co.uk provides unique coverage of the capital’s politics, development and culture with no paywall and no ads. Nearly all its income comes from individual supporters. For £5 a month or £50 a year they receive in-depth newsletters and London event offers. Pay via any Support link on the website or by becoming a paying subscriber to publisher and editor Dave Hill’s Substack.