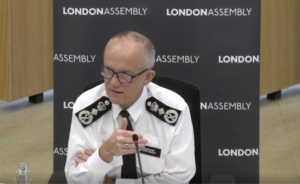

The Metropolitan Police Service has let down Londoners and urgent changes are needed to rebuild policing by consent, the new Met commissioner Mark Rowley admitted today during his first appearance before the London Assembly’s police and crime committee as the capital’s chief police officer.

Rowley took over as Met commissioner in September, succeeding Cressida Dick who resigned in April following a clash with Sadiq Khan over her plans for boosting public confidence in the police. His frank description of what he has inherited will not have been easy listening for his predecessor.

“What really struck me was pretty much a straight line percentage fall in confidence in the Met over the past four years, from the high 60s to the high 40s, with some communities and geographies where it is much lower than that,” he said.

There were “too many examples” of officers behaving appallingly, and inconsistent responses from senior officers, he added. “I’ve heard too many black and women colleagues saying they have had unpleasant experiences in the organisation which had been dealt with too feebly.”

Rowley said further evidence of the scale of the challenge would be revealed in the review into the Met’s culture and standards by veteran troubleshooter Louise Casey, commissioned by Dick last years, and which would be published shortly.

“It will show we haven’t been as robust and determined about maintaining high standards as we should have been,” he said. Standard setting had been inconsistent, with a “lack of confidence from leaders on where to draw a line in terms of behaviour that is just not appropriate in a modern organisation”.

The “good majority” of officers, who had a “real appetite for clearer standards and a stronger approach”, had also been let down, Rowley said. But it was wrong to talk of “bad apples”, or service attitudes reflecting those in wider society.

“We enforce the law, we have unique powers given to us by Parliament, and you can’t have the trust of citizens if are not aiming for the highest standards in terms of your own integrity,” he said. “We can’t be average. We have to be above the average.”

As well as his new push on rooting out attitudes and behaviours he described as “corrupting” the integrity of the service, the new commissioner set out plans to beef up neighbourhood police teams, with closer working with communities, and to address day-to-day concerns, including response times, chronicled in last month’s critical Inspectorate of Constabulary report which saw the Met put under a higher level of scrutiny and support.

Under a new mantra – “more trust, less crime, high standards” – Rowley also highlighted an overhaul of management supervision and a focus on updating technology for “command and control” response to emergencies and case management to avoid “delivering something that looks like Woolworths policing in an Amazon age”.

And he expressed caution over the now former Home Secretary Priti Patel’s urgings in a letter last month that the Met’s current allocation of some 4,500 extra police officers should be in place by the end of March next year.

“Just recruiting headlong without bringing the right people in with the right support could be destabilising. I am concerned about whether it’s possible or wise to go at that pace,” he said, adding that he was now “reviewing” that deadline.

Responding to questions from committee chair Susan Hall, leader of the Assembly’s Conservative group, Rowley said the environmental protests currently underway, including blocking roads in central London, had not reached the threshold of serious disruption which would justify tougher police action.

The protests had taken up the equivalent of 2,156 officer days over 11 days, he said, with 338 arrests. “But the law is very clear that just blocking a road in itself is not serious disruption,” he added. “I would love to close this down more quickly but I don’t have the legal power to do that.”

The police and crime committee meeting can be viewed in full here.

On London strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. Become a supporter for just £5 a month. You will even get things for your money. Details here.