Bad news for haters of Sadiq Khan, of whom there are many, some of them warped beyond repair: the London Mayor has reached the end of a difficult year riding high in the esteem of Londoners and has his principal challenger for the next mayoral election lined up for a first round knock out. That is the message of the most recent YouGov findings for Queen Mary University of London. Its previous survey, held in September, had seen Khan’s approval rating plunge to a net +4 per cent – it had once stood at a dazzling +35. But the latest poll, conducted early this month, found it had recovered to +11. And Khan’s lead over Conservative candidate Shaun Bailey was, for Tories, an ominous 55 per cent to just 28 per cent in terms of Londoners’ first preference votes.

Were that position replicated in real votes come May 2020, Khan would become the first winner of a London Mayor election with no need for second preferences to be counted. Strikingly, Khan’s position is even stronger than that of his party, Labour, while Bailey’s is actually trailing that of the Tories. At this stage, Bailey’s hopes look limited to shoring up the shrinking London Tory base and salvaging what respectability he can. By contrast, Khan, to the comic puzzlement of his dimmer detractors – those crackpots convinced that he has spent his 30 months at City Hall so far transforming the capital into a criminal “war zone” full of “no-go areas” presumably in preparation for imposing Sharia Law – looks pretty much unbeatable.

But does he deserve to?

Judging the performance of London Mayors entails a number of things: knowing what their uneven and limited set of “hard” powers actually comprises and monitoring the outcomes of their deployment; recognising the wider and less precise significance of mayoral “soft” power and judging how well it has been used; appraising how effectively they articulate the collective mood of Londoners, including when seeking additional resources and autonomy from national government; tracking the delivery of manifesto promises; and pondering whether having an eye on securing future, higher political office in future is affecting what they are – and are not – doing now.

By one measure, Sadiq Khan’s 2018 has been a runaway triumph. Even his fiercest critics – in fact, particularly them – acknowledge that his political operation has continued to deliver great results, at least for Sadiq Khan. These have been secured both in the pubic mayoral arena and in the zanier London backwoods of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party.

Harrumph all you like about Khan’s promiscuous posing for selfies – it works for him and, yes, it is part of his job. To be visible and accessible to Londoners, including in such ways, is integral to the task of a directly elected Mayor. And, to switch from the superficial to the deadly serious, no assessment of Khan’s conduct as a figurehead since his election in May 2016 should understate the demands placed on him by the succession of unwelcome unscheduled events that largely defined his first 18 months in charge: the EU referendum result just two months into his term; the derailment of a Tramlink train in Croydon, also in 2016; and the 2017 Westminster Bridge, London Bridge and Finsbury Park terror attacks.

Khan answered well those early calls to his leadership pulpit, providing reassertions of what we might call core London values of openness and solidarity in diversity – values Khan himself embodies. But 2018 placed different demands on his public leadership role. The September plunge in his poll ratings, notably among white, working-class and older voters, followed a summer in which the year’s violent death toll in the capital ticked up towards 100.

The Mayor pointed to rises in recorded serious violence offences across the whole country and railed repeatedly against continuing big reductions in government funding for the Metropolitan Police Service. His opponents accused him of blame-shifting, and the charge may have stuck up to a point. But the Khan operation keeps a careful eye on London public opinion. The austerity card seems to play well. Bailey, who trades on youth worker experience and being the voice of “the street”, claims cash could be redeployed by reducing “waste” but makes no criticism of the cuts. Much good that seems to have done him so far.

Meanwhile, Khan and close advisers have won a subterranean and subtler victory with Labour members and backers this year. The Mayor Khan who made that famous “power” speech to the 2016 party conference – a barely veiled rebuke to Corbyn’s leadership approach – and who backed Owen Smith’s leadership challenge of that year, has long since left the stage. In January, he announced a new pay deal for London’s bus drivers. This kept a manifesto promise, but a celebratory photo op with Unite general secretary and bedrock Corbyn-backer Len McCluskey at Merton bus garage drew cynical comment from some senior Labour borough figures, who thought – and still think – the Mayor too pre-occupied with nurturing his Labour power base to find sufficient time to help the likes of them deliver Labour policies on the ground. “This year’s defining optic,” is how one sceptic wearily described the McCluskey pic.

The immediate backdrop at that time was Khan’s natural desire to be reselected as Labour’s 2020 mayoral candidate free from any turbulence, perhaps in the form of a Momentumite challenger seeking to stir up the sort of Corbynite fervour that ousted “moderate” sitting councillors in Haringey. By the end of August it was clear he would stroll it, but tales of assiduous advance groundwork have reinforced the view of detractors – Labour as well as Conservative – that Khan’s administration is better at political management than delivering policy results.

Throughout this year, from the boroughs and elsewhere, have come complaints that while Khan is “outward-facing” in media terms he is not very accessible when you need him. Business bosses, borough leaders and others like to feel they have the personal backing of the Mayor when taking big decisions, if not directly then from lieutenants they can be certain speak for him. He, after all, can make it harder for them to deliver, whether by intervening with formal planning powers or simply not conveying enthusiasm to other bodies whose support is needed.

But Khan’s inner circle comprises his political managers and fixers rather than his policy deputies, and that doesn’t suit everyone. The most unexpected people make unfavourable comparisons with Ken Livingstone’s time at City Hall. Livingstone’s core team comprised policy directors (they would be called deputy mayors now) who spoke directly for the Mayor himself on housing, transport, policing and so on. Though derided by enemies as “Ken’s cronies”, they were valued by insiders because they helped make things happen. “Ken wanted to get things done,” a major property developer told me earlier this year. “With Sadiq, like Boris [Johnson], you feel he’s got half an eye on his next job and doesn’t want to do anything too risky.”

Is that fair? Team Khan, of course, demurs. And there are good arguments against what Centre for London’s Richard Brown says might be termed the more “charismatic” mayoral model adopted in different ways by both Livingstone and Johnson, the former by using the profile of his office and force of his personality to schmooze, muscle and convene in pursuit of strategic goals, the latter rather more whimsically. For some, Livingstone was too hands-on and Johnson the opposite, though with capable people around him doing the hard work. Bear all of the above in mind. But other factors too that have influenced the progress of Khan’s mayoralty so far, and they’ve remained conspicuous in 2018.

Luck has been one of them. There hasn’t been too much of it about. The 2017 terror attacks probably resulted in Khan’s brand being strengthened in the eyes of supporters, but just imagine the disruption, the devouring of time and energy, the sheer, exhausting weight of responsibility. It took time to recover. Then there’s the wider national and political climate to consider, with a Brexit-swamped, subliminally anti-London national government still swinging the spending axe. “It was great under Boris,” reflected a London transport boss at a social function back in the spring. “Plenty of money and a crap Mayor.” Those days are gone and it is in transport, the policy area over which London mayors have the greatest range of powers, where good fortune has been in short supply for Mayor Khan.

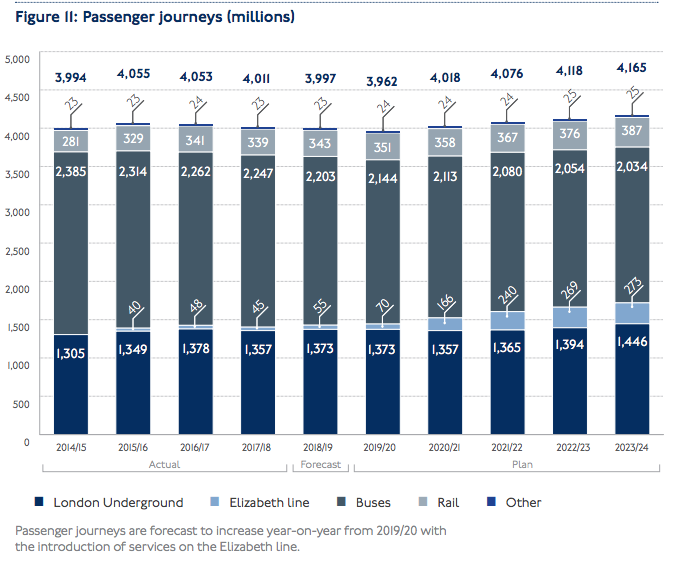

A constellation of dark stars has continued to form in 2018, and the shape they make is a financial black hole. London is now the planet’s sole big international city to receive no government grant for running its daily transport systems. At the same time, its income from fares is falling. Why? Largely because demand for public transport has continued to fall following years of increases. The Mayor’s partial fares freeze has had an effect too, though its defenders will always argue that passenger numbers would have reduced even further without it. The same case is made for the hopper bus fare, which has proven very popular.

The postponement of Crossrail’s opening, announced on 31 August, was the news Khan and Transport for London (TfL) needed least of all – they were depending more and more heavily on future fares income from the service. The announcement might have felt sudden, but concerns had been made very public months before. Given this, the quarrel about whether or not Khan, who chairs TfL’s board, knew for sure what was coming at the end of July and should have said something at the time rather than a few weeks later feels a little academic, for all the recriminations and furore.

The Crossrail delay heaped higher the disappointment of Westminster Council’s ditching the Oxford Street pedestrianisation plans that it, the Mayor, TfL, the big West End retailers and local community groups had been working on, apparently productively, for two years. Khan’s manifesto goal of a “tree-lined avenue from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch” died in 2018. Attaining it, complemented by the core of Crossrail coming on line, would have been his flagship first term achievement.

Public sector finance analysts Moodys said in November it believed TfL can “manage the delay” using available resources and “spending flexibly”, but that its ability to cope with other reverses is now reduced. It also stressed that Crossrail remains absolutely vital to TfL’s long-term financial stability. But something new is happening across the London transport landscape. No single cause can be firmly identified, but the upshot, as TfL’s annual end of year Travel In London report set out, is a continuing fall in demand, taking in cycling, Underground and bus use alike. None of this is good for transport budgets, with fares revenues hit and questions raised about value for public money. There is considerable alarm about the future of London’s bus service, which is by far the capital’s most-used public transport mode. Plans for a seven per cent capacity cut prompted the boss of London’s biggest bus service operator to give On London a rare interview, expressing his concerns.

The Mayor has had more to celebrate on housing policy, thanks to his affordable homes investment programmes. City Hall regards the £4.82 billion it has secured from central government to allocate to housing associations and councils to be a bit of a triumph, and says this money will help to fund the starting of 116,000 new “genuinely affordable” homes by 2022. The London Assembly housing committee, which helpfully monitors the progress of affordable housebuilding, has pointed out that fewer than 5,500 affordable homes supported by the Mayor were actually completed – as opposed to merely started – in 2017/18, though it should be noted that it usually takes a couple of years to build a house and that Khan’s administration began pretty much from a standing start.

In April, City Hall was able to announce that over 12,500 new affordable homes were started (as opposed to completed) during the 2017/18 financial year, hitting the Mayor’s annual target. Most of these were low cost home ownership dwellings, aimed at Londoners on middle incomes. The following month, money was earmarked for councils to boost their house building programmes and in October £1 billion was distributed to 27 of the 32 boroughs. In this case, the vast majority of the nearly 14,000 homes are to be let at “social rent levels” (see my explainer about London affordable homes here).

A second strand of the Mayor’s home building policy concerns new homes on publicly-owned land, which effectively means TfL’s. The transport body believes over 10,000 new homes can eventually be built on land it owns, but this is a much smaller and slower programme. During 2017/18 contracts were signed to develop some 3,800 homes on TfL land, half of them “affordable”. In June, the Mayor announced that 70 “genuinely affordable” homes will be built by London Community Land Trust on two sites (one in Tower Hamlets, the other in Lambeth) and in September, TfL said it is seeking a partner to form a joint venture company to build 3,000 build-to-rent homes.

Khan’s manifesto promised to give Londoners “first dibs” on some market homes. In February, a group of commercial developers and housing associations said they would sign up to a voluntary agreement that new homes for market sale priced below £350,000 – and therefore likely to be in Outer London – would be available only to resident Londoners and people working in the capital for a one month period after they were put on the market. This wasn’t quite the “first dibs” arrangement promised, which referred to new homes built on public land, but the arrangement was made with people who might also be eligible for low cost home ownership products in mind. Khan had also sought to boost housebuilding by using his considerable power to intervene in borough planning decisions, showing willing several times to push through schemes in the face of local objections as long as the “genuinely affordable” percentage proposed reaches his 35 per cent threshold.

One of Khan’s more politically contentious moves on housing in 2018 was his change of stance on estate regeneration schemes that entail the demolition of existing social housing, such that residents have to give their support through a ballot as a condition for the scheme receiving mayoral funding. His draft guidance on the issue had rejected ballots, and his change of mind was interpreted by many – not least in Labour boroughs keen to renew some of their old housing stock – as a capitulation to the Momentum Left and others.

Certainly, the inclusion of a ballot requirement was applauded in those quarters and by the Green Party, also often in the thick of opposition to regeneration projects, as a victory for powerless communities. However, the first three ballots held under Khan’s new rules have produced resounding endorsements by residents of plans to knock down and replace their homes. All three have been in relation to small estates and these are early days. But it will be interesting to see if the trend continues. If it does, it will demonstrate an appetite for estate regeneration among estate residents themselves that activists opposed to it have long denied exists.

All these initiatives reflect pretty well on the Mayor’s Home for Londoners team. They do, however, also need to be seen in a wider context that throws into relief the limitations on the Mayor’s ability to influence housing supply in London overall. He can shape it, regulate it and add to it according to his priorities and means, but the wider market dominates the scene. London prices have fallen a little. But so, alas, has overall housing supply – which means affordable supply suffers as well. Khan’s draft new London Plan, which will begin its examination in public in the New Year, puts total demand at 66,000 new homes a year. That looks a long way from being achieved.

We’ll end on violent crime because its victims should be remembered and because fear of it and even the thought of its presence in our midst corrodes this city’s soul. A week before Christmas, the BBC compiled a list of all the murder, manslaughter and self-defence killing victims in London during 2018. There are lots of reasons for questioning crime statistics, but dead bodies tend to speak for themselves. The London homicide total as of 28 December was 132. Spend some time with that bleak inventory. The variety of the victims and the brief stories of their deaths surprised me a little. The list also prompted reflection on which cases have been solved and which apparently have not; which I recall receiving media coverage and which I don’t; and which ones better police intelligence or more police resources might have prevented.

We can only speculate on that last point, but it is hard to see how the year-on-year paring down of police personnel numbers can have made no difference at all. During Boris Johnson’s mayoralty City Hall politicians quarrelled endlessly about exactly how many warranted officers the Met employed at any given time. The disputed figure was always somewhere above 30,000. The current Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime is now projecting a fall to well below that figure and the Mayor has said that there are now 3.3 police officers for every 1,000 Londoners compared with 4.1 in 2010.

He raised his share of council tax this year by 5.1 percent – an average of 27 pence per week – in order to put an additional £49 million into the Met, and looks set to repeat the exercise in 2019. A further £55 million raised from business rate income was allocated to the service too. Mayor Khan says the proportion of the Met’s budget provided through City Hall is now 23 per cent compared with 18 per cent in 2010. He, like many other London government leaders, favours more autonomy. But this looks very like the phenomenon disparaged in local government circles as “devolve and leave”.

Arguments about government funding in all the main policy areas of mayoral power and control – transport, housing and policing – seem unlikely to dissipate in 2019, especially as pre-election political flurries intensify. They will take place as that festival of barminess and brinkmanship we call Brexit continues towards its unknown conclusion and as the emerging outline of a nation likely to depend more heavily on London’s economic power than ever takes its uncertain shape. Mayor Khan may find it harder to fulfil some of his policy pledges, but the former lawyer will have a persuasive case for his own defence – and, of course, the political skills with which to make it.