The 2019 election is the first since 1951 in which the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition have both had their constituencies in London. Yesterday, I looked at Boris Johnson’s Uxbridge & South Ruislip. Now it is the turn of Jeremy Corbyn’s home turf of Islington North. Johnson’s links with suburban, ambivalent Uxbridge are recent and rather transactional. But Corbyn’s politics are deeply rooted in Islington North and the complicated, unruly heart of the world city.

It is an extremely safe Labour seat. Corbyn has represented it since 1983, and it has voted Labour continuously ever since a by-election in 1937. Corbyn’s majority soared above 30,000 in 2017. While there might be less mass enthusiasm in 2019 and some possible upturn from the Liberal Democrats and Greens following the severe squeeze on their votes last time, the Labour leader’s re-election is guaranteed.

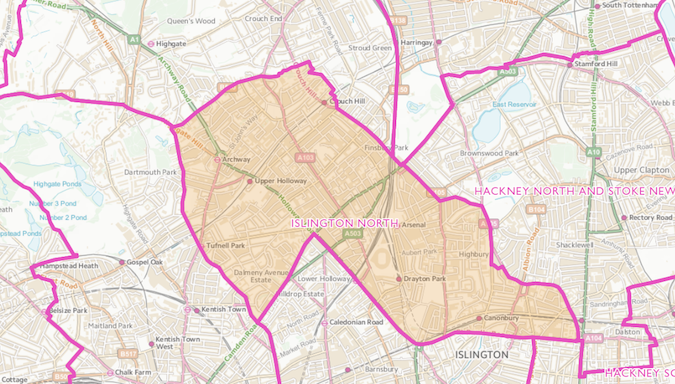

Islington North is geographically the smallest constituency in the country, covering only 7.35 square kilometres of densely-packed urban territory in inner north London. It stretches from the lower slopes of Highgate around Archway along the north east side of the borough of Islington down to Highbury and Newington Green. It is a relentlessly urban landscape of terraces and council estates, broken up by railway lines and major roads. Highbury Fields is the largest open space. The main local landmarks are the Emirates Stadium, the Archway bridge and the now-closed Holloway prison.

Although it has been Labour for over 80 years, Islington North started out as a late Victorian “Villa Tory” constituency, described then as “mainly a residential district of the upper middle classes”. Contemporary Islington North, however, has all the demographic markers of a safe Labour seat. To understand it, first one should throw a lot of the witless “Islington” and “north London” clichés about cappuccinos and avocados into the bin with great force.

On the recently compiled Index of Multiple Deprivation, the government’s broad measure of the extent of poverty, bad health and restricted lives, Islington North is 119th out of the 533 English constituencies, keeping company with classic “left behind towns” territory like Mansfield (117th) and Wigan (125th). It has the eighth highest concentration of social housing of the 650 UK constituencies (40.3 per cent), with large council-built estates such as Andover and Elthorne. Its population is predominantly of working age – it is very low in its share of retired people – and while a lot of Corbyn’s constituents do work in the professions (eighth highest constituency) and have high-level qualifications (13th highest), even many of these are under pressure from job insecurity and high housing costs.

Islington North is ethnically diverse, but with no single minority ethnicity dominating. It is a mixture of people from across the world, many of whom have come to London in need – of work, of asylum, of freedom. Like neighbouring Camden, it is natural territory for exiles, its political climate affected by anti-apartheid South Africans, socialist Chileans and Palestinians. As Rosa Prince points out in her book Comrade Corbyn, this international aspect of Islington North chimes with Corbyn’s long-standing ideological positions and strengthens his identification with the wretched of the Earth.

Irish people are the minority most strongly associated with Islington North – the area has occasionally been called “County Holloway”. Leaving aside constituencies in Northern Ireland, it has the largest proportion of Irish-born residents (three per cent) of any constituency except Brent Central, and a much larger community that is Irish by family origin and identification. Again, Corbyn could hardly help identifying with a mostly working-class local community that faced discrimination and hostility, and did so in the 1980s when he sometimes gave the impression of being the only Sinn Féin MP who took his seat at Westminster.

Islington’s politics in Corbyn’s formative years in the 1970s and 1980s were a cauldron of bitter internal Labour factionalism. Broadly, there were three factions: a very old-fashioned working-class Irish political machine; a modernising right wing associated with the early days of the professional classes’ rediscovery of Islington; and a New Left that championed the interests of women and minorities. When the Social Democratic Party (SDP) was formed in 1981, the non-left Islington factions broke away, giving the new party all three local MPs and a majority on the council.

But Labour swept aside the SDP in a local election landslide in 1982 and the left took control under the leadership of Margaret Hodge. In 1983, the same happened with the parliamentary seats (reduced to two in boundary changes). Corbyn achieved the unusual distinction of defeating not one but two incumbent MPs, both elected for his own party in 1979 – John Grant (outgoing MP for Islington Central) represented the SDP and Michael O’Halloran (Islington North) who stood as an Independent but reflected the modernising and machine tendencies that had both gone over to the SDP.

The left’s victories in 1982 and 1983 were not the end of factionalism, nor of the SDP (the Lib Dems, formed from the SDP and the old Liberal Party, came back to run the council in 1999-2010). The left split acrimoniously over rate-capping in 1985 and the right made a comeback in the 1990s. Although there was more mutual tolerance than in the 1970s there were still intense conflicts, for instance during the battle in 1995-97 around the national executive committee’s veto on Islington left councillor Liz Davies becoming candidate in Leeds North East.

Islington North, therefore, is close to Corbyn’s core as a politician in a way that Uxbridge simply is not to Johnson’s. Two terms as Mayor may have given Johnson a broad perspective as a London politician, while Corbyn’s interest in London is both more parochial and more global. The quarrelsome urban politics of the world city, the assembling of coalitions of disparate minorities, the identification with the oppressed and the tolerance of violent movements of the oppressed, are all there in Islington North, as is a ferocious commitment to infighting within the Labour Party.

To Corbyn, recent NEC shenanigans to impose left candidates and leadership cronies will merely be payback for similar sagas from the old days – Martha Osamor, Liz Davies, Sharon Atkin – when the boot was on the other foot. Islington North has a long memory for injustice and grievance, and not much sentimentality about how it is redressed.

Map: Ordnance Survey under Open Government Licence.

On London intends to provide the fullest possible coverage of the 2019 general election campaign in the capital, along with other big issues for the city. The website depends on financial support from readers to pay its freelance writers. Just £5 a month makes an important difference. To donate to On London, click here. Thank you.

> Dear ONLONDON Editors,

> Somebody in the media reported that they would vote ABC,

> ‘Anyone but Corbyn ‘

>

> But ABC could be used for other interesting principles

>

> 1. Anti Boris Campaign

> 2. A British Compromise

> 3. A Better Commons

> 4. A Brexit Chaos

>

> It leads to a further interesting consideration. There are many people who view the lamentable state of British politics as rooted in the characters of the two leaders of the main parties.

> Would the atmosphere and quality of the debate in the Commons not be improved if both were removed from office?

> How could that be achieved? A very simple solution lies in the hands of the voters in two consituencies.

>

> If the labour voters in the Islington North constituency and the Tory voters in the Uxbridge & South Ruislip constituency would abstain from voting, both BJ and JC would be removed from the Commons. Neither would become the next incumbent of 10 Downing street.

>

> As the song ‘Happy Talk’ from the musical South Pacific puts it so succinctly – ‘you have to have a dream!

>

> Best wishes from Germany

>

> Michael Gibson

> Romeisstrasse 14a

> 91315 Hoechstadt

> Germany

Telephone number +4991937485