Only four of London’s parliamentary constituencies changed hands in the general election of 12 December and the overall balance sheet left the three largest parties with exactly the same numbers of seats as they had won in 2017: Labour remained way ahead with 49, while the Conservatives finished with 21 and the Liberal Democrats with three. Yet beneath the no-change surface some significant questions were raised about how next year’s London Mayor election campaign might unfold.

The results in London further underlined how different the capital’s political landscape is from that of the rest of Britain. While big bricks in Labour’s “red wall” in the North and Midlands were turning blue, the party’s London’s heartlands – as, interestingly, they are never termed – held firm. The only seat the party lost was Kensington and even the “Labour Leave” seat of Dagenham & Rainham was (just about) held.

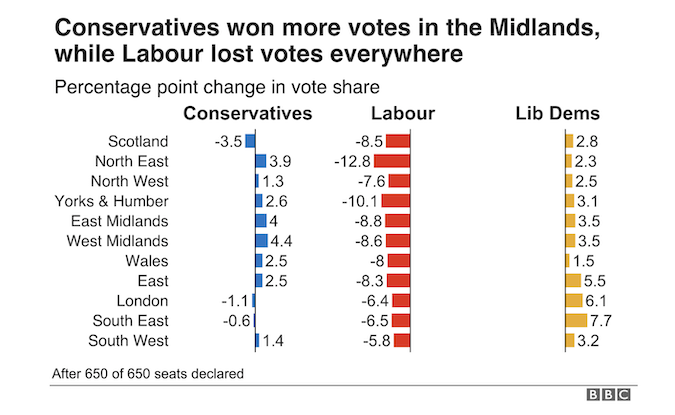

Labour’s vote share across Greater London did fall significantly compared with two years ago – as the BBC chart below shows, it dropped by 6.4 per cent. However, this was a smaller reduction than Labour experienced almost everywhere else in Britain. And while the Labour Party nationally was crushed by the Conservatives, who emerged with an 80-seat majority, its surviving London vote share appears to bode well for its 2020 London Mayor candidate, the incumbent Sadiq Khan.

While the Conservatives’ vote share went up nationally almost everywhere else compared with 2017, it slipped just a little in the capital – down by 1.1 per cent – demonstrating that the Tories’ London problem is still far from solved. The Lib Dems, by contrast, saw their vote share rise by 6.1 per cent. Yet that is far less than they will have hoped for, given that they were London’s most popular party in May’s European elections. The “Lib Dem surge” did not maintain its full force.

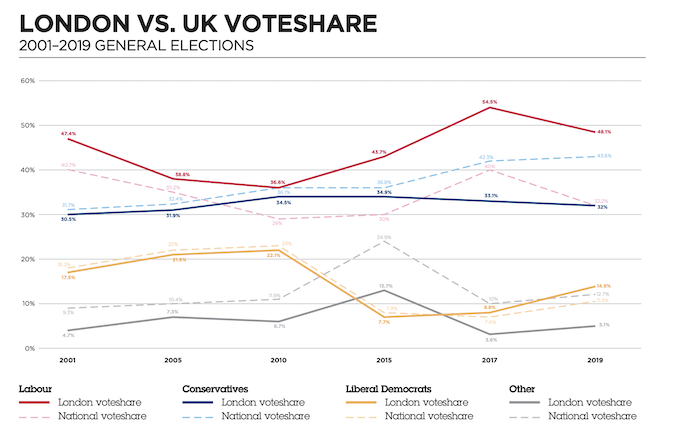

Despite its relative loss of popularity, Labour still secured a formidable 48.1 per cent of the popular vote in London at the general election, compared with the Conservatives’ 32 per cent and the Lib Dems’ 14.9 per cent, as the graph below from London Communications Agency‘s briefing shows. And those are the numbers that matter when trying to anticipate what the May 2020 London Mayor result might be.

In 2016, Sadiq Khan became London Mayor with a 44.2 per cent share of Londoners’ first preference votes – slightly lower than the proportion of Londoners who voted for his party ten days ago. His vanquished Tory opponent Zac Goldsmith – the now twice former MP for Richmond Park – got only 35 per cent of first preferences, but was better than the vote share his party attracted in London in the general election.

Of course, general elections and mayoral elections are very different: turnout is lower, the issues are London-specific and voters are asked to judge which individual they would like to directly elect to City Hall in a more personalised contest under a different electoral system. Even so, the party’s general election vote share was at a very similar figure to its candidate’s rating in a November YouGov poll for Queen Mary University of London’s Mile End Institute. Khan came top with 46 per cent. And his Conservative challenger Shaun Bailey was a distant second on just 23 per cent.

All of that said, the electoral terrain is already shifting in and around London, with implications for mayoral candidates of all parties and none.

Khan, the Lib Dem hopeful Siobhan Benita and the Green Party’s Sian Berry (who finished third in 2016) have all been emphasising their pro-Remain credentials. Now, Boris Johnson’s resounding general election win has shot the Brexit fox. The question for London Mayor candidates is whether it is dead or will now enjoy a vigorous afterlife, even after the UK leaves the European Union at the end of next January.

The spirit of opposition to Brexit could yet endure as a symbol of the London of open values Khan so effectively personified in 2016. The matter of London’s importance to the UK’s economy post-Brexit might become more high profile, providing fresh grounds for calling for more resources and devolution of powers from a Prime Minister who called for those very things when he was London Mayor.

At the same time, Johnson’s electoral debt to the North and Midlands could mean that, following a largely anti-London election, he will could the capital to the back of the queue. As LCA’s briefing puts it, all candidates will “have to figure out how best to make the capital’s claim to a Prime Minister who attention is clearly elsewhere”.

Alternatively, will Brexit lose much of its potency, allowing other issues to rise up the agenda to the possible advantage of Khan’s rivals? Bailey has been talking almost constantly about crime. Rory Stewart, the former Tory minister running as an Independent who was in third place in the November opinion poll on 13 per cent, having declared his candidacy the previous month? Though still formulating his policy positions, Stewart has said there would be “less politics and more action” if he became Mayor.

Benita and Berry, who were respectively fourth and fifth in the November poll, will surely be reflecting on what their greatest strengths now are, with issues such as climate change, transport, air quality and housing perhaps gaining greater salience for London’s electors. For his part, Khan has already moved to distance himself from Jeremy Corbyn’s disastrous leadership of Labour, echoing the stance he took in 2016. He is surely still the hot favourite to win again, but the first mayoral opinion poll of 2020 could make for intriguing reading.

OnLondon.co.uk is dedicated to providing fair, thorough, anti-populist coverage of London’s politics, development and culture. It depends on donations from readers and would like to pay its freelance contributors better. Can you spare £5 (or more) a month? Follow this link to donate. Thank you.

With Brexit out of the way we can expect campaigns fought on the issues that matter most to most Londoners and are within the powers of the Mayor and GLA. The obvious ones are crime, housing, transport and skills (where budgets are being passed from Central Government). The mantra of “Tory Cuts” will not be enough to defend the GLAs track record of failure if the other parties come up with radical new policies for restoring community policing, encouraging empty rooms and properties onto the market, reforming Transport for London and delivering vocational training in partnership with local employers. The Mayor will have to spend the period between now and the election demonstrating either that his current policies can deliver or that he has the will to identify and deliver what Londoners need.

The irony here is that while Labour nationally has been rejected by the electorate Labout Councils in London (for example the Rokhsana Fiaz administration in Newham ) are continuing to increase Council Tax and cut services. The GLA has also increased its portion of Council Tax take.

The level of, and recent rises in, Council Tax in London may well be an issue. This applies to both the borough component and the GLA precept.