Sadiq Khan’s margin of victory in the mayoral election, while comfortable, will have disappointed London Labour and the Mayor himself. It is not the first time opinion polls have been unduly flattering to Labour in the run-up to Greater London Authority or borough elections, but to win with a smaller lead than in 2016 was well below expectations.

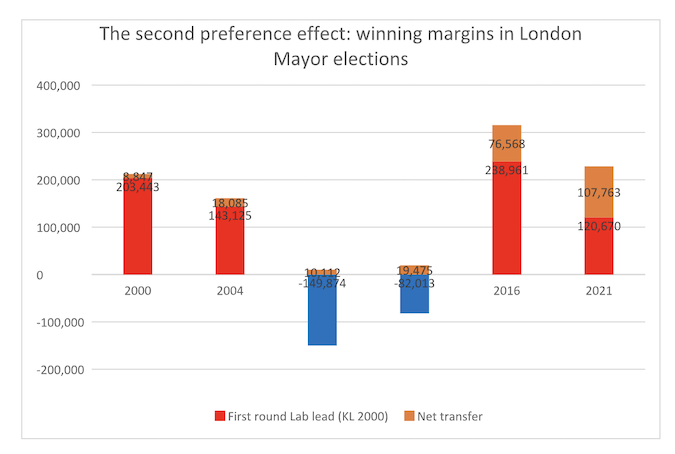

One aspect of the election, however, did produce the best result for any mayoral candidate since elections started in 2000 – both Khan’s share of the second preference vote and the resulting boost to his winning total were the largest yet. Had Ken Livingstone made up as much ground in second preference votes in 2012 as Khan did in 2021, he would have defeated Boris Johnson.

The result perhaps reflects Londoners’ verdict on Khan quite well – a lukewarm level of positive support, but no real desire to see anyone else become Mayor in his place. Shaun Bailey’s share of second preference votes was, by contrast, the weakest of any second-round contender.

Part of the reason for Labour’s growing advantage is the nature of the candidates. In their better years for transfers the Conservatives nominated two candidates who in their different ways proved inoffensive to many non-Tories – the affable Steve Norris in 2000 and 2004, and a more liberal edition of Johnson in 2008 and 2012. Livingstone, first as an Independent and then as a Labour candidate, was more of a Marmite proposition.

Khan, as a mainstream Labour figure, is more attractive while the last two Conservatives, Bailey and Zac Goldsmith have been abrasive and highly partisan. They have both polled reasonably well, given their party’s weak baseline in London, but campaigned in ways that could have been calculated to put off second preferences from supporters of most other parties. The sudden jump in 2016 in the proportion of second votes swinging to Labour must have a lot to do with candidate factors.

The 2021 election took place in a curious atmosphere, fuelled by excessive media coverage of the Laurence Fox campaign. It was tempting for people on the left to try to achieve a double success in the election by casting a first preference for “joke” candidates to humiliate Fox, and then swing behind Khan in the second round.

This strategy succeeded up to a point – YouTuber Niko Omilana did overtake Fox, but Count Binface and another YouTuber, Max Fosh, fell short. The extent to which this was a deliberate strategy is underlined by the fact that Binface voters were the savviest of the lot in how to use their second preferences effectively – they fell overwhelmingly to Khan, with fewer wasted than on any other candidate.

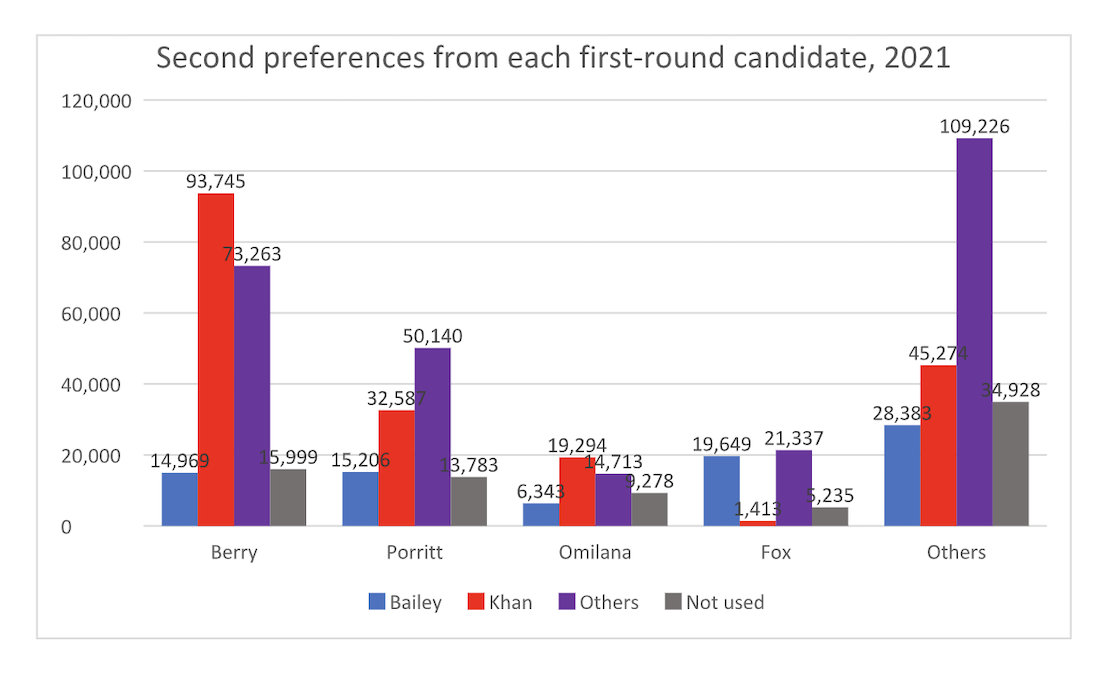

Another explanation for the trend is the increasing importance of the Green Party among the “other” candidates. Their share has risen in every mayoral election, from 2.2 per cent in 2000 to Sian Berry’s 7.8 per cent in 2021, and their supporters have consistently used their second preferences to help Labour. Other parties – the Liberal Democrats, UKIP and the like – have become less important.

Opinion among the Lib Dems has moved between different elections. A slightly smaller proportion of Luisa Porritt’s voters gave Khan their second preference compared to 2016, but Bailey fared significantly worse than Goldsmith did so the net benefit to Khan was larger. Two Conservatives have “won” the Lib Dem second preferences – Steve Norris in 2000 and Boris Johnson during the Coalition in 2012.

The most important element of the second round is the Green vote. It is the largest single source of second preferences and it goes strongly Labour, forming the majority of the votes Sadiq Khan gained in 2016 and 2021. The Lib Dem vote is smaller and falls out less overwhelmingly in one direction – the Labour candidate picked up more than two thirds of the usable Lib Dem second preferences this time, but the advantage gained was 17,000 compared to 79,000 from the Greens.

The transferred votes from Omilana gave Khan a net boost of another 13,000 votes over Bailey, while Fox’s pegged Khan’s lead back by 18,000. Fox voters were unusual on the right in making effective use of the preferential system – often conservatives do not bother, or cast second preferences for other candidates who won’t make it to the second round – but fully 44 per cent of the Fox vote transferred to Bailey.

The votes for the other 14 candidates split in Khan’s favour – a net gain of 17,000 votes – but they divided into three categories. Voters for five of the candidates (Binface, Fosh, Valerie Brown, Richard Hewison and Mandu Reid) leaned strongly to Khan, giving him a combined net addition of 22,000 votes. Another group (Kam Balayev, Piers Corbyn, Vanessa Hudson, Steve Kelleher, Farah London and Nims Obunge) did not split strongly either way (net 2,000 votes for Khan) and a third group (Peter Gammons, David Kurten, Brian Rose) gave a net 8,000 votes to Bailey, although their vote was less effectively channelled in that direction than Fox’s.

Under the bonnet

Preference voting multiplies the quantity of interesting numbers that an election can produce, if you are inclined to be interested in electoral numbers in the first place. With 20 candidates for Mayor, there were 420 possible permutations of first and second choice. For every single combination, there were at least a few dozen voters for whom it made perfect sense.

Two hundred and thirty-three Londoners used their first preference for Gammons, the UKIP candidate and their second preference for Hewison of Rejoin EU, and 230 Hewison voters returned the compliment. A massive data table like this enables us to see patterns in the votes for the smaller parties. This helped in grouping the smaller party candidates when I analysed second preference flows from the “others”.

A lot of calculations later, I was able to measure candidates by how much affinity their voters had with each other – the dense little table below summarises how likely, compared to chance, each combination of voters was to preference each other: blue is a “cold” relationship, red is “warm”. They are ordered by their proximity to Sadiq Khan voters. Omilana supporters were the closest to Labour, followed by those for Berry, Binface, Reid and Hewison.

There was mutual affinity between several candidates in the middle – Brown, Obunge, London, Fosh – and a very close relationship between several candidates of a broadly libertarian or right wing bent – Corbyn, Kurten and Rose. Gammons, Bailey and Fox were adjacent but distinct. Fox and Khan voters were the most antipathetic to each other. There was also a clear, small YouTube party among the electorate – mutual support between Omilana and Fosh was much higher than chance. This all suggests that many supporters of minor parties are not voting haphazardly, but making some quite well-informed and sophisticated choices.

Supporters of the two leading candidates are able to use their second preference vote as a sort of participation rosette for their favourite smaller party. Both Khan and Bailey voters gave this accolade to Berry of the Green Party – Khan’s by a huge margin and Bailey’s by a slim lead over Fox, Porritt and… Khan. About 11-12 per cent of supporters of Labour and the Conservatives actually give the main rival of each their second preference. This might be interpreted in several ways – perhaps they are saying that the other side are the party they want to come second, perhaps it’s a preference for major-party government of London, perhaps even in these polarised times it’s a hand across the aisle.

Conclusion

One of the problems with the Supplementary Vote system, in addition to the confusing ballot paper it produced on this occasion, is that it requires voters to guess which of the candidates will be the top two. While this has not been in much doubt in any London election, 43 per cent of third-party voters gave their second preference to candidates other than Khan and Bailey in 2021.

Another 13 per cent either left it blank or voted for the same candidate on second and first preference – which does no harm, but is effectively the same as leaving it blank. The system works a lot less well in London than it did in Cambridgeshire, where 84 per cent of third-placed Lib Dems had their second preferences counted in a three-candidate race.

The Supplementary Vote is a variant of a system used rather more widely – the Alternative Vote (AV), in which there is a single row of boxes to mark and voters put “1” for their first choice, “2” for their second and so on until they are bored or indifferent between the remaining candidates. Given London’s complex politics, the large numbers of candidates in the last two elections and the confusion in 2021, AV seems more likely to reflect voters’ nuanced views and give more people an effective choice.

Unfortunately, the government is choosing to go in the other direction by making fewer votes count and introducing the First Past the Post system. It is surely not coincidental that it has moved against preference voting now that the Conservatives have absorbed UKIP’s electorate while Labour, Lib Dem and Green remain divided but likely to give each other second preferences.

Khan’s strong showing on second preferences in 2021, although it is likely to be a high point, will not deter them. Meanwhile, proportional representation remains for the London Assembly because without it the Conservatives would not get their fair share of seats. I deplore this, as a Londoner, voter and electoral systems buff. We should improve the system, so that it allows even more freedom of expression for voters, not bulldoze it and replace it with something cruder.

On London is a small but influential website which strives to provide more of the kind of journalism the capital city needs. It depends on financial help from readers and is able to offer them something in return. Please consider becoming a supporter. Details here.

Thanks for that very interesting and sympathetic analysis.

I wondered if perhaps the apparently perverse UKIP/Rejoin EU combination you mention, was influenced by those candidates being adjacent on the ballot paper. Voters not remembering they’d be expected to give a second choice, so not having prepared one, might just quickly put the other cross somewhere apparently random, favouring an adjacent row.

(Or else they misread Rejoin as Reject!)